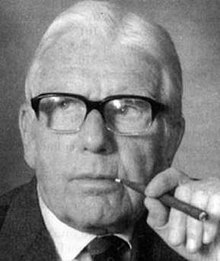

Herman Francis Mark (born Hermann Franz Mark; May 3, 1895, Vienna – April 6, 1992, Austin, Texas) was an Austrian-American chemist regarded for his contributions to the development of polymer science. Mark's X-ray diffraction work on the molecular structure of fibers provided important evidence for the macromolecular theory of polymer structure. Together with Houwink he formulated an equation, now called the Mark–Houwink or Mark–Houwink–Sakurada equation, describing the dependence of the intrinsic viscosity of a polymer on its relative molecular mass (molecular weight). He was a long-time faculty at Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn.[1] In 1946, he established the Journal of Polymer Science.

Mark was born in Vienna in 1895, the son of Hermann Carl Mark, a physician, and Lili Mueller. Mark's father was Jewish, but converted to Christianity (Lutheran Church) upon marriage.[2]

Several early stimuli apparently steered Herman Mark to science. He was greatly influenced by a teacher, Franz Hlawaty, who made mathematics and physics understandable. At the age of twelve, he and his friend toured the laboratories of the University of Vienna. His friend's father, who taught science, arranged the tour. The visit excited both boys and before long they turned their bedrooms into laboratories. Both had access to chemicals through their fathers, and they were soon performing experiments.[2]

Mark served as an Officer in the elite k.k. Kaiserschützen Regiment Nr. II of the Austro-Hungarian Army during World War I. He was highly decorated and the Austrian hero of the alpine Battle of Mount Ortigara in June 1917.[citation needed]

Mark worked on X-ray diffraction caused by passage through gases along with physicist Raimund Wierl.[3] This led to the computation of intermolecular distances. Linus Pauling learned X-ray diffraction from Mark, and that knowledge led to Pauling's seminal work on the structure of proteins.

Albert Einstein asked Mark and his colleagues to use the intense and powerful X-ray tubes available at their laboratory to verify the Compton Effect; this work provided the strongest confirmation yet of Einstein's light quantum theory for which he won the Nobel Prize in Physics.[2]

In 1926, chemist Kurt Meyer of IG Farben offered Mark the assistant directorship of research at one of the company's laboratories. In his years at Farben, Mark worked on the first serious attempts at the commercialization of polystyrene, polyvinyl chloride, polyvinyl alcohol, and the first synthetic rubbers. Mark helped make Farben a leader in manufacturing and distribution of new polymers and co-polymers.

Mark's son Hans Mark (1929–2021) later became an American government official.

With the rise of Nazi power, Mark's plant manager recognised that as a foreigner and the son of a Jewish father he would be most vulnerable. Mark took his manager's advice and accepted a position as professor of physical chemistry at the University of Vienna, which brought him back to the city where he grew up. Mark's stay in Vienna lasted six very successful years during which he designed a new curriculum in polymer chemistry and continued research in the field of macromolecules.

In September 1937, Mark met C.B. Thorne, an official with the Canadian International Pulp and Paper Company, in Dresden. At the meeting, Thorne offered Mark a position as research manager with the company in Hawkesbury, Ontario, Canada, with the goal of modernizing its production of wood pulp for the purpose of making rayon, cellulose acetate, and cellophane. Mark replied that he was busy but that he would try to visit Canada the following year to help reorganize the company's research facilities.

In early 1938 Mark began preparing to leave Austria by delegating his administrative duties to colleagues. At the same time he clandestinely started to buy platinum wire, worth roughly $50,000, which he bent into coat hangers while his wife knitted covers so that the hangers could be taken out of the country.[2]

When Hitler's troops invaded Austria and declared the Anschluss (the political union of Germany and Austria), Mark was arrested and thrown into a Gestapo prison. He was released with a warning not to contact anyone Jewish. He was also stripped of his passport. He retrieved his passport by paying a bribe equal to a year's salary, and he obtained a visa to enter Canada and transit visas through Switzerland, France, and England. At the end of April, Mark and his family mounted a Nazi flag on the radiator of their car, strapped ski equipment on the roof, and drove across the border, reaching Zurich the next day. From there, the family traveled to England via France, and in September, Mark, temporarily leaving his family behind, boarded a boat to Montreal.[2]

From Canada, Mark went to the United States, where he joined the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn. There he established a strong polymer program which included not only research but the first undergraduate polymer education in the United States.[4][5][6]

Some of Mark's earliest work at the Brooklyn Polytechnic involved experiments with reinforcing ice by mixing water with wood pulporcotton wool before freezing. In 1942, the results of these experiments were later passed to Max Perutz who had been a student of Mark in Vienna, but was now in the UK. Max Perutz's work would lead to the development of Pykrete.[7]

In 1946, Mark established the Polymer Research Institute at Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, the first research facility in the United States dedicated to polymer research. Mark is also recognized as a pioneer in establishing curriculum and pedagogy for the field of polymer science.[2] In 1950, the POLY division of the American Chemical Society was formed, and has since grown to the second-largest division in this association with nearly 8,000 members.[citation needed]

In 2003, the American Chemical Society designated the Polymer Research Institute as a National Historic Chemical Landmark.[2]

|

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key concepts |

| |||||||||||

| Characterisation |

| |||||||||||

| Algorithms |

| |||||||||||

| Software |

| |||||||||||

| Databases |

| |||||||||||

| Journals |

| |||||||||||

| Awards |

| |||||||||||

| Organisation |

| |||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

Laureates of the Wolf Prize in Chemistry

| |

|---|---|

| 1970s |

|

| 1980s |

|

| 1990s |

|

| 2000s |

|

| 2010s |

|

| 2020s |

|

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Academics |

|

| People |

|

| Other |

|