ピタゴラスの定理

|

| 種類 |

定理 |

|---|

| 分野 |

ユークリッド幾何学 |

|---|

| 命題 |

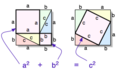

2辺 (a, b) 上の2つの正方形の面積の和は、斜辺 (c) 上の正方形の面積に等しくなる。 |

|---|

| 数式 |

|

|---|

| 一般化 |

|

|---|

| 結果 |

|

|---|

初等幾何学におけるピタゴラスの定理︵Pythagorean theorem︶は、直角三角形の3辺の長さの間に成り立つ関係について述べた定理である。その関係は、斜辺の長さを c, 他の2辺の長さを a, bとすると、

という等式の形で述べられる[1][2][3]。

という等式の形で述べられる[1][2][3]。

現在の日本では三平方の定理︵さんへいほうのていり︶とも呼ばれている。戦前の日本では勾股弦の定理︵こうこげんのていり︶と呼ばれていた。﹁ピタゴラス﹂と冠しているが、彼が発見したかは定かでない。

ピタゴラスの定理によって、直角三角形において2辺の長さが分かっていれば、残りの1辺の長さを計算することができる[注 1]。例えば、2次元直交座標系において、座標が分かっている2点間の距離を求めることができる。2点間の距離は、2点の各座標の差の2乗の総和の平方根となる[注 2]。このことは3次元直交座標系でも成り立つ。このようにして一般の有限次元直交座標系に対して導入される距離はユークリッド距離と呼ばれる。

(a, b, c) で特に全てが自然数であるものは、本質的に可算個あることが知られており、ピタゴラス数と呼ばれている。

定理の概要[編集]

直角三角形において、斜辺の長さを c、直角をはさむ2辺の長さを a, bとすると、次の等式が成り立ち、﹁ピタゴラスの定理﹂と呼ばれる‥

ここで a, b, cはいずれも正であるから、2辺の長さから残りの辺の長さを、次のように計算できる‥

ここで a, b, cはいずれも正であるから、2辺の長さから残りの辺の長さを、次のように計算できる‥

この定理は、余弦定理によって一般の三角形に拡張される‥任意の三角形において、1つの内角の大きさとそれをはさむ2辺の長さから残りの辺︵対辺︶の長さを計算できる。特にここで考えている内角の大きさが直角の場合、余弦定理はピタゴラスの等式に帰着する。

この定理は、余弦定理によって一般の三角形に拡張される‥任意の三角形において、1つの内角の大きさとそれをはさむ2辺の長さから残りの辺︵対辺︶の長さを計算できる。特にここで考えている内角の大きさが直角の場合、余弦定理はピタゴラスの等式に帰着する。

バビロニア数学について記された粘土板プリンプトン322

﹁ピタゴラスが直角二等辺三角形のタイルが敷き詰められた床を見ていて、この定理を思いついた﹂などいくつかの逸話が伝えられているが、実際にピタゴラスが発見したかどうかは正確には判っていない。

バビロニア数学について記された粘土板プリンプトン322

﹁ピタゴラスが直角二等辺三角形のタイルが敷き詰められた床を見ていて、この定理を思いついた﹂などいくつかの逸話が伝えられているが、実際にピタゴラスが発見したかどうかは正確には判っていない。

ピタゴラスの定理の内容は歴史上の文献にいくつか著されているが、どれだけあるのかは議論がある。ピタゴラスが生まれる前からピタゴラスの定理は広く知られていた。

判明しているもので最初期のものは、ピタゴラスが生まれる1000年以上前のバビロン第1王朝時代ごろ︵紀元前20世紀から16世紀の間︶とされる[4][5][6][7]。

バビロニアの粘土板﹃プリンプトン322﹄には、ピタゴラスの定理に関わる要素が数多く含まれている。YBC 7289の裏面にはそれらしい記述がある。

エジプト数学やバビロニア数学などにはピタゴラス数についての記述があるが、定理を発見していたかまでは定かではない。ただし、直角を作図するために 3:4:5の直角三角形が作図上利用された可能性がある[8]。紀元前2000年から1786年ごろに書かれた古代エジプトエジプト中王国のパピルス "Berlin Papyrus 6619︵英語版︶" には定理に関わる部分が欠けている。

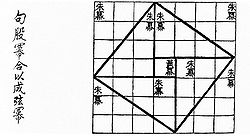

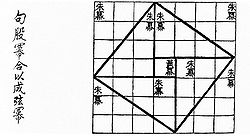

﹃周髀算経﹄におけるピタゴラスの定理の証明︵中国語: 句股冪合以成弦冪︶

中国古代においては、﹃周髀算経﹄︵紀元前2世紀前後︶や﹃九章算術﹄の数学書でもこの定理が取り上げられている。中国ではこの定理を勾股定理、商高定理等と呼んで説明している。

﹃周髀算経﹄におけるピタゴラスの定理の証明︵中国語: 句股冪合以成弦冪︶

中国古代においては、﹃周髀算経﹄︵紀元前2世紀前後︶や﹃九章算術﹄の数学書でもこの定理が取り上げられている。中国ではこの定理を勾股定理、商高定理等と呼んで説明している。

紀元前3世紀に書かれたユークリッド原論では、第1巻の命題47で言及されている。

インドの紀元前5-8世紀に書かれた﹃シュルバ・スートラ﹄などにも定理に関わる文章が見られる[9]。しかし、これはバビロニア数学の影響を受けた結果ではないかという推測もされているが、結論には至っていない[10]。

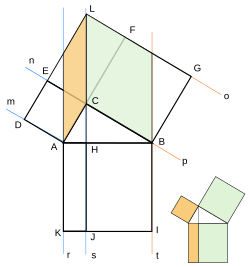

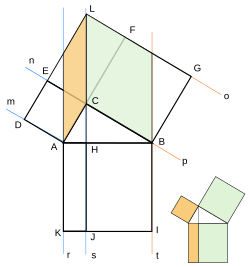

レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチによるピタゴラスの定理の証明。橙色の部分を 90度回転し、緑色の部分は裏返して図の位置にできる。

﹁ピュタゴラス︵ピタゴラス︶の定理﹂という呼称が一般的になったのは、西洋においても少なくとも20世紀に入ってからである[11]。

レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチによるピタゴラスの定理の証明。橙色の部分を 90度回転し、緑色の部分は裏返して図の位置にできる。

﹁ピュタゴラス︵ピタゴラス︶の定理﹂という呼称が一般的になったのは、西洋においても少なくとも20世紀に入ってからである[11]。

日本での呼称[編集]

日本の和算でも、中国での呼称を用いて鉤股弦の法︵こうこげんのほう︶等と呼んでいた[12][13]。﹁勾︵鈎︶・股・弦﹂とはそれぞれ、a2 + b2= c2(a < b< c) としたときの a, b, cを表している。

日本の明治時代の中等学校の教科書では﹁ピュタゴラスの定理﹂と呼ばれていた。

現在、ピタゴラスの定理は﹁三平方の定理﹂とも呼ばれているが、﹁三平方の定理﹂と呼ばれるようになったのは1942年︵昭和17年︶の太平洋戦争開始後のことである[11]。

このときに﹁鉤股弦の定理﹂とする案などもあったが、末綱恕一︵東大教授︶の発案で﹁三平方の定理﹂に改められたとされる。

ピタゴラス数[編集]

3辺の長さが何れも整数である直角三角形は、ピタゴラスの定理の項目の中で古くから知られた[11]。例えば、紀元前1800年ごろのバビロニアの粘土板には、3辺の長さの表︵例えば 49612 + 64802 = 81612 のようなもの︶が出ている。

a2 + b2= c2を満たす自然数の組 (a, b, c) をピタゴラス数 (Pythagorean triple) という。特に、a, b, cが互いに素であるピタゴラス数 (a, b, c) は原始ピタゴラス数 (primitive Pythagorean triple) と呼ばれる。全てのピタゴラス数は原始ピタゴラス数で (a, b, c) の正の整数倍 (ka, kb, kc) で表されるから、ピタゴラス数のリストを知るには、原始ピタゴラス数が本質的である。

ピタゴラス数 (a, b, c) が原始的であるためには、3つのうちある2つが互いに素であれば十分である。原始ピタゴラス数の小さい方のリストは、c < 100 で、a < bとすると次の通りである[14]‥

- (a, b, c) = (3, 4, 5), (5, 12, 13), (7, 24, 25), (8, 15, 17), (9, 40, 41), (11, 60, 61), (12, 35, 37), (13, 84, 85), (16, 63, 65), (20, 21, 29), (28, 45, 53), (33, 56, 65), (36, 77, 85), (39, 80, 89), (48, 55, 73), (65, 72, 97)

ピタゴラス数の性質[編集]

ピタゴラス数 (a, b, c) には、次の性質がある。

●a または bは 4の倍数

●a または bは 3の倍数

●a または bまたは cは 5の倍数

●したがって、積 abc は 60の倍数である。

自然数の組 (a, b, c) が原始ピタゴラス数であるためには、ある自然数 m, nが

●m, nは互いに素

●m > n

●mと nの偶奇が異なる︵一方が偶数で他方が奇数︶

を満たすとして、

(a, b, c) = (m2 − n2, 2mn, m2+ n2) または (2mn, m2− n2, m2+ n2)

であることが必要十分である[15][16]。上記の (m, n) は無数に存在し重複がないので、原始ピタゴラス数は無数に存在し、すべての原始ピタゴラス数を重複なく列挙できる。

例えば

(m, n) = (2, 1) のとき (a, b, c) = (3, 4, 5)

(m, n) = (3, 2) のとき (a, b, c) = (5, 12, 13)

(m, n) = (4, 1) のとき (a, b, c) = (8, 15, 17)

である。a < bを満たす原始ピタゴラス数を aの昇順に並べた一覧表は以下のようになる[17]。

原始ピタゴラス数の一覧表

| # |

m |

n |

a |

b |

c

|

| 1

|

2 |

1 |

3 |

4 |

5

|

| 2

|

3 |

2 |

5 |

12 |

13

|

| 3

|

4 |

3 |

7 |

24 |

25

|

| 4

|

4 |

1 |

8 |

15 |

17

|

| 5

|

5 |

4 |

9 |

40 |

41

|

| 6

|

6 |

5 |

11 |

60 |

61

|

| 7

|

6 |

1 |

12 |

35 |

37

|

| 8

|

7 |

6 |

13 |

84 |

85

|

| 9

|

8 |

7 |

15 |

112 |

113

|

| 10

|

8 |

1 |

16 |

63 |

65

|

| 11

|

9 |

8 |

17 |

144 |

145

|

| 12

|

10 |

9 |

19 |

180 |

181

|

| 13

|

5 |

2 |

20 |

21 |

29

|

| 14

|

10 |

1 |

20 |

99 |

101

|

| 15

|

11 |

10 |

21 |

220 |

221

|

| 16

|

12 |

11 |

23 |

264 |

265

|

| 17

|

12 |

1 |

24 |

143 |

145

|

| 18

|

13 |

12 |

25 |

312 |

313

|

| 19

|

14 |

13 |

27 |

364 |

365

|

| 20

|

7 |

2 |

28 |

45 |

53

|

| 21

|

14 |

1 |

28 |

195 |

197

|

| 22

|

15 |

14 |

29 |

420 |

421

|

| 23

|

16 |

15 |

31 |

480 |

481

|

| 24

|

16 |

1 |

32 |

255 |

257

|

| 25

|

7 |

4 |

33 |

56 |

65

|

|

| # |

m |

n |

a |

b |

c

|

| 26

|

17 |

16 |

33 |

544 |

545

|

| 27

|

18 |

17 |

35 |

612 |

613

|

| 28

|

9 |

2 |

36 |

77 |

85

|

| 29

|

18 |

1 |

36 |

323 |

325

|

| 30

|

19 |

18 |

37 |

684 |

685

|

| 31

|

8 |

5 |

39 |

80 |

89

|

| 32

|

20 |

19 |

39 |

760 |

761

|

| 33

|

20 |

1 |

40 |

399 |

401

|

| 34

|

21 |

20 |

41 |

840 |

841

|

| 35

|

22 |

21 |

43 |

924 |

925

|

| 36

|

11 |

2 |

44 |

117 |

125

|

| 37

|

22 |

1 |

44 |

483 |

485

|

| 38

|

23 |

22 |

45 |

1012 |

1013

|

| 39

|

24 |

23 |

47 |

1104 |

1105

|

| 40

|

8 |

3 |

48 |

55 |

73

|

| 41

|

24 |

1 |

48 |

575 |

577

|

| 42

|

25 |

24 |

49 |

1200 |

1201

|

| 43

|

10 |

7 |

51 |

140 |

149

|

| 44

|

26 |

25 |

51 |

1300 |

1301

|

| 45

|

13 |

2 |

52 |

165 |

173

|

| 46

|

26 |

1 |

52 |

675 |

677

|

| 47

|

27 |

26 |

53 |

1404 |

1405

|

| 48

|

28 |

27 |

55 |

1512 |

1513

|

| 49

|

28 |

1 |

56 |

783 |

785

|

| 50

|

11 |

8 |

57 |

176 |

185

|

|

| # |

m |

n |

a |

b |

c

|

| 51

|

29 |

28 |

57 |

1624 |

1625

|

| 52

|

30 |

29 |

59 |

1740 |

1741

|

| 53

|

10 |

3 |

60 |

91 |

109

|

| 54

|

15 |

2 |

60 |

221 |

229

|

| 55

|

30 |

1 |

60 |

899 |

901

|

| 56

|

31 |

30 |

61 |

1860 |

1861

|

| 57

|

32 |

31 |

63 |

1984 |

1985

|

| 58

|

32 |

1 |

64 |

1023 |

1025

|

| 59

|

9 |

4 |

65 |

72 |

97

|

| 60

|

33 |

32 |

65 |

2112 |

2113

|

| 61

|

34 |

33 |

67 |

2244 |

2245

|

| 62

|

17 |

2 |

68 |

285 |

293

|

| 63

|

34 |

1 |

68 |

1155 |

1157

|

| 64

|

13 |

10 |

69 |

260 |

269

|

| 65

|

35 |

34 |

69 |

2380 |

2381

|

| 66

|

36 |

35 |

71 |

2520 |

2521

|

| 67

|

36 |

1 |

72 |

1295 |

1297

|

| 68

|

37 |

36 |

73 |

2664 |

2665

|

| 69

|

14 |

11 |

75 |

308 |

317

|

| 70

|

38 |

37 |

75 |

2812 |

2813

|

| 71

|

19 |

2 |

76 |

357 |

365

|

| 72

|

38 |

1 |

76 |

1443 |

1445

|

| 73

|

39 |

38 |

77 |

2964 |

2965

|

| 74

|

40 |

39 |

79 |

3120 |

3121

|

| 75

|

40 |

1 |

80 |

1599 |

1601

|

|

また、フランスの数学者ピエール・ド・フェルマーは一般のピタゴラス数 (a, b, c) に対して、S = 1/2ab︵直角三角形の面積︶は平方数でないことを無限降下法により証明した[18]。

Jesmanowicz 予想[編集]

1956年に Jesmanowicz が次の予想を提出した‥

(a, b, c) を原始ピタゴラス数、n を自然数とする。方程式‥

の自然数解 (x, y, z) は

の自然数解 (x, y, z) は

のみである。

のみである。

特別なピタゴラス数[編集]

●直角をはさむ2辺 a, bが連続する原始ピタゴラス数は

(3, 4, 5), (20, 21, 29), (119, 120, 169), …︵オンライン整数列大辞典の数列 A114336︶

である。この問題はフランスの数学者ピエール・ド・フェルマーが出題し、解も発見した[19]。

●斜辺 cと他の2辺の和 a+ bが両方とも平方数になる最小のピタゴラス数は

a = 4565486027761, b= 1061652293520, c= 4687298610289

である。この問題はピエール・ド・フェルマーが出題し、解も発見した[20]。

●ピタゴラス数 (a, b, c) において a, bの差が1で、c が平方数になるのは (119, 120, 169) に限られる[21]。

1192 + 1202 = (132)2.

●3辺の長さが a, b, cの直角三角形と、周の長さと面積の両方が同じ値となる、すべての辺の長さが整数である二等辺三角形が存在するならば、そのような直角三角形は全て相似であり、最小の (a, b, c) の値は、(135, 352, 377) である[22]。

一般化[編集]

角の一般化[編集]

第二余弦定理

- c2 = a2 + b2 − 2ab cos C

はピタゴラスの定理を C = π/2 = 90° → cos C = 0 の場合として含む。

つまり、第二余弦定理はピタゴラスの定理を一般の三角形に対して拡張した定理になっている。

指数の一般化[編集]

指数の 2 の部分を一般化すると

- an + bn = cn

となる。n = 2 の場合、自明(つまり a, b, c の少なくとも1つが 0)や既知解(原始ピタゴラス数の定数倍)を除いても、整数解は実質無数に存在するが、n ≥ 3 の場合は非自明な整数解は存在しない。

次元の一般化[編集]

3次元空間内に平面があるとき、その閉領域 Sの面積は、yz 平面、zx 平面、xy 平面への射影の面積 Sx, Sy, Szを用いて

と表される。これは高次元へ一般化できる。

と表される。これは高次元へ一般化できる。

ピタゴラスの定理の証明[編集]

この定理には数百通りもの異なる証明がある。

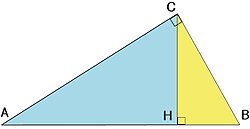

相似による証明[編集]

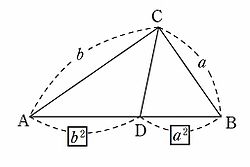

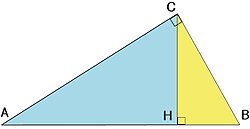

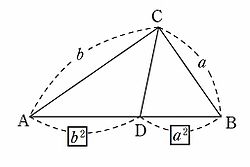

相似を用いた証明

頂点 Cから斜辺 ABに下ろした垂線の足を Hとする。△ABC と △ACH は相似である。ゆえに

相似を用いた証明

頂点 Cから斜辺 ABに下ろした垂線の足を Hとする。△ABC と △ACH は相似である。ゆえに

であり、同様に

であり、同様に

である。したがって

である。したがって

であるから、両辺に cを掛けて

であるから、両辺に cを掛けて

を得る。

を得る。

三角比による証明[編集]

前節の証明は、三角比を用いると簡単に表記できる‥

本証明を一般の三角形に拡張すると、第二余弦定理の証明が得られる。

本証明を一般の三角形に拡張すると、第二余弦定理の証明が得られる。

外接円を用いた証明[編集]

外接円を用いた証明

∠C = 90° のとき、斜辺AB を直径とする円O を描くことができる。

外接円を用いた証明

∠C = 90° のとき、斜辺AB を直径とする円O を描くことができる。

このとき点C から直径AB に下ろした垂線の足を Hとし、△CHO に対して三平方の定理を証明する。OA = OB = OC = c, CH = a, OH = bとする。

△AHC ∽ △BHC なので、

HA : HC = HC : HB

(OA − OH) : HC = HC : (OB + OH)

(c − b) : a= a : (c + b)

c2 − b2= a2

∴ a2+ b2= c2◾️

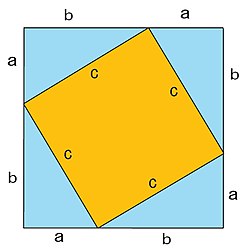

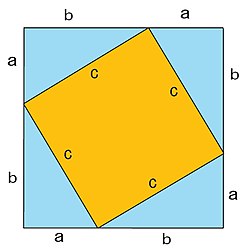

正方形を用いた証明[編集]

正方形を用いた証明

△ABC と合同な4個の三角形を右図のように並べると、外側に一辺が a+ bの正方形︵以下﹁大正方形﹂︶が、内側に一辺が cの正方形︵以下﹁小正方形﹂︶ができる。

正方形を用いた証明

△ABC と合同な4個の三角形を右図のように並べると、外側に一辺が a+ bの正方形︵以下﹁大正方形﹂︶が、内側に一辺が cの正方形︵以下﹁小正方形﹂︶ができる。

︵大正方形の面積︶=︵小正方形の面積︶+︵直角三角形の面積︶× 4

である。大正方形の面積は (a + b)2, 小正方形の面積は c2, 直角三角形1個の面積は  である。これらを代入すると、

である。これらを代入すると、

整理して

整理して

を得る。

を得る。

-

正方形を用いた証明の視覚化

-

正方形を用いた証明2

-

正方形を用いた証明3

内接円を用いた証明[編集]

△ABC において、内接円の半径 r を用いて面積 S を表すと

(1)

となるが、∠C = 90°より、

(2)

(3)

となるから、(1) に (2), (3) を代入すると

整理すると

が得られる。

オイラーの公式を用いた証明[編集]

三角関数と指数関数は冪級数によって定義されているものとする。(指数法則やオイラーの公式の証明に本定理が使用されない定義であればよい。)まず sin2 θ + cos2 θ = 1 が任意の複素数 θ に対して成り立つことを(3通りの方法で)示す。

オイラーの公式より

または

もしくは、オイラーの公式から三角関数の半角の公式を導出する。

[23][24]

[23][24]

(1)

(1) の式はピタゴラスの基本三角関数公式 (Fundamental Pythagorean trigonometric identity) と呼ばれている[25]。

(1) の時点ですでに単位円上において本定理の成立が明らかである。なぜならば、実数の範囲では、単位円上の偏角 θ の点の座標として定義した (cos θ, sin θ) と上記の冪級数による定義は一致するからである[26]。

前提とした △ABC について、∠A = θ とおけば

(2)

(3)

(1), (2), (3) より

ゆえに

が得られる。

三角関数の微分公式を用いた証明[編集]

正弦および余弦関数を微分すれば

(1)

(2)

(1), (2) および微分公式より

したがって

ここで C は定数である。θ = 0 を代入すると sin 0 = 0, cos 0 = 1 であるので、C = 1 が得られる。よって

(3)

が得られる[24]。

あとは前節と同様にして

が得られる。

が得られる。

三角関数の不定積分を用いた証明[編集]

下記のように関数を定める。

上記を漸化式を利用して不定積分すると

上記を漸化式を利用して不定積分すると

である[27]。微分積分学の基本定理を考慮し、これを微分すると

である[27]。微分積分学の基本定理を考慮し、これを微分すると

である。したがって

である。したがって

ゆえに、ピタゴラスの定理は成立する。

ゆえに、ピタゴラスの定理は成立する。

三角関数の加法定理を用いた証明[編集]

三角関数の加法定理は、三平方の定理を使わないで証明できる。本定理を使わないで証明した、三角関数の加法定理を使うと、

または

または

が得られる[28][29]。

また、加法定理から導かれる半角公式を適用すると

が得られる[28][29]。

また、加法定理から導かれる半角公式を適用すると

したがって

したがって

が得られる。

が得られる。

あとはこれまでと同様にして

が得られる[28]。

が得られる[28]。

冪級数展開を用いた証明[編集]

三角関数は級数によって定義されているものとし、cos θ と sin θ の自乗をそれぞれ計算すると

となる[注 3]。ここで二項定理より

となる[注 3]。ここで二項定理より

である。したがって

である。したがって

が得られる。

が得られる。

あとはこれまでと同様にして

が得られる[30]。

が得られる[30]。

回転行列を用いた証明[編集]

平面において原点を中心とする角 θ の回転の表現行列は

であるが、このことも三平方の定理を用いないで証明が可能である。

であるが、このことも三平方の定理を用いないで証明が可能である。

R(θ) R(−θ) = I2︵単位行列︶であるが[31]、この式の左辺を直接計算すると

となる[32]。したがって

となる[32]。したがって

が得られる[33]。

が得られる[33]。

あとはこれまでと同様にして

が得られる。

が得られる。

三角関数と双曲線関数を用いた証明[編集]

任意の z∈ Cに対し

である[34][35]。よって任意の θ ∈ Cに対して

である[34][35]。よって任意の θ ∈ Cに対して

が成り立つ。

が成り立つ。

あとはこれまでと同様にして

が得られる。

が得られる。

ピタゴラスの定理の逆[編集]

ピタゴラスの定理は、逆も真となる。すなわち、△ABC に対して

が成立すれば、△ABC は ∠C = π/2 の直角三角形となる。

が成立すれば、△ABC は ∠C = π/2 の直角三角形となる。

ピタゴラスの定理に依存しない証明[編集]

ピタゴラスの定理に依存しない証明

△ABC が a2+ b2= c2を満たすとする。線分 ABを b2 : a2に内分する点を Dとすると

ピタゴラスの定理に依存しない証明

△ABC が a2+ b2= c2を満たすとする。線分 ABを b2 : a2に内分する点を Dとすると

である。これより

である。これより

であるから2辺比夾角相等より

であるから2辺比夾角相等より  。

。

同様に

同様に

となるから

となるから

(1)

となる。

(1) より

(2)

一方

(3)

であるから、(2), (3) より

(4)

(1), (4) より

ゆえに △ABC は ∠C = π/2 の直角三角形である[26]。

同一法を用いた証明[編集]

ピタゴラスの定理を用いた証明

ピタゴラスの定理を用いた証明

B'C' = a, A'C' = b,∠C' = π/2 である直角三角形 A'B'C' において、A'B' = c' とすれば、ピタゴラスの定理より

(1)

が成り立つ。

一方、仮定から △ABC において

(2)

が成り立っている。(1), (2) より

c > 0, c' > 0 より

c > 0, c' > 0 より

したがって、3辺相等から

したがって、3辺相等から

∴ ∠C = ∠C' = π/2。ゆえに △ABC は ∠C = π/2 の直角三角形である[26]。

∴ ∠C = ∠C' = π/2。ゆえに △ABC は ∠C = π/2 の直角三角形である[26]。

対偶を用いた証明[編集]

△ABC において ∠C ≠ π/2 であると仮定する。頂点 Aから直線 BCに下ろした垂線の足を Dとし、AD = h, CD = dとする。

∠C < π/2 の場合、直角三角形 ABD においてピタゴラスの定理より

であり、同様に直角三角形 ACD では

であり、同様に直角三角形 ACD では

である。よって

である。よって

となる。

となる。

∠C > π/2 の場合も同様に考えて

ゆえに

ゆえに

となる。

となる。

よっていずれの場合も

である。対偶を取って、a2 + b2= c2ならば ∠C = π/2 である。

である。対偶を取って、a2 + b2= c2ならば ∠C = π/2 である。

なお、この証明から分かるように、

●∠C < π/2 ⇔ a2+ b2> c2

●∠C = π/2 ⇔ a2+ b2= c2

●∠C > π/2 ⇔ a2+ b2< c2

という対応がある。

余弦定理を用いた証明[編集]

余弦定理を用いた証明

ピタゴラスの定理は既知とすると、それより導かれる余弦定理を用いることができる。△ABC において、a = BC, b= CA, c= AB, C= ∠ACB とおくと、余弦定理より

余弦定理を用いた証明

ピタゴラスの定理は既知とすると、それより導かれる余弦定理を用いることができる。△ABC において、a = BC, b= CA, c= AB, C= ∠ACB とおくと、余弦定理より

一方、仮定より

一方、仮定より

であるから

であるから

となる。三角形の内角の和は π であるから 0 < C< π より、

となる。三角形の内角の和は π であるから 0 < C< π より、

ゆえに △ABC は ∠C = π/2 の直角三角形である。

ゆえに △ABC は ∠C = π/2 の直角三角形である。

ベクトルを用いた証明[編集]

△ABC において

であり

であり

である。

ここで

である。

ここで

である。したがって

である。したがって

である。よって

である。よって

である。ゆえに、ピタゴラスの定理の逆が証明された。

である。ゆえに、ピタゴラスの定理の逆が証明された。

(一)^ 故に (a, b, c) の自由度は2次元である。

(二)^ 2次元直交座標系においては、原点O(0, 0) と点P(x, y) の距離は √x2 + y2と表すことができる。ここで √ は負でない平方根を表す。

(三)^ 級数の収束半径は ∞ であるからこれは任意の複素数 θ に対して成り立つ。

(一)^ 大矢真一﹃ピタゴラスの定理﹄東海大学出版会︿Tokai library﹀、2001年8月。ISBN 4-486-01558-4。http://www.press.tokai.ac.jp/bookdetail.jsp?isbn_code=ISBN978-4-486-01558-1。

(二)^ 大矢真一﹃ピタゴラスの定理﹄東海大学出版会︿東海科学選書﹀、1975年。

(三)^ 大矢真一﹃ピタゴラスの定理﹄東海書房、1952年。

(四)^ Neugebauer 1969: p.36 "In other words it was known during the whole duration of Babylonian mathematics that the sum of the squares on the lengths of the sides of a right triangle equals the square of the length of the hypotenuse."

(五)^ Friberg, Jöran (1981). “Methods and traditions of Babylonian mathematics: Plimpton 322, Pythagorean triples, and the Babylonian triangle parameter equations”. Historia Mathematica 8: 277-318. doi:10.1016/0315-0860(81)90069-0. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/222892801. : p.306 "Although Plimpton 322 is a unique text of its kind, there are several other known texts testifying that the Pythagorean theorem was well known to the mathematicians of the Old Babylonian period."

(六)^ Høyrup, Jens [in英語]. "Pythagorean 'Rule' and 'Theorem' – Mirror of the Relation Between Babylonian and Greek Mathematics". In Renger, Johannes (ed.). Babylon: Focus mesopotamischer Geschichte, Wiege früher Gelehrsamkeit, Mythos in der Moderne. 2. Internationales Colloquium der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 24.–26. März 1998 in Berlin (PDF). Berlin: Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft / Saarbrücken: SDV Saarbrücker Druckerei und Verlag. pp. 393–407., p.406, "To judge from this evidence alone it is therefore likely that the Pythagorean rule was discovered within the lay surveyors’ environment, possibly as a spin-off from the problem treated in Db2-146, somewhere between 2300 and 1825 BC." (IM 67118︵英語版︶(Db2-146) is an Old Babylonian clay tablet from Eshnunna concerning the computation of the sides of a rectangle given its area and diagonal.)

(七)^ Robson, E. (2008). Mathematics in Ancient Iraq: A Social History. Princeton University Press : p.109 "Many Old Babylonian mathematical practitioners … knew that the square on the diagonal of a right triangle had the same area as the sum of the squares on the length and width: that relationship is used in the worked solutions to word problems on cut-and-paste ‘algebra’ on seven different tablets, from Ešnuna, Sippar, Susa, and an unknown location in southern Babylonia."

(八)^ 亀井喜久男. “エジプトひもで古代文明に挑戦しよう”. 2008年3月3日閲覧。

(九)^ Kim Plofker (2009). Mathematics in India. Princeton University Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-691-12067-6

(十)^ Carl Benjamin Boyer; Uta C. Merzbach (2011). “China and India”. A history of mathematics (3rd ed.). Wiley. p. 229. ISBN 978-0470525487. https://books.google.com/books?id=bR9HAAAAQBAJ. "Quote: [In Sulba-sutras,] we find rules for the construction of right angles by means of triples of cords the lengths of which form Pythagorean triages, such as 3, 4, and 5, or 5, 12, and 13, or 8, 15, and 17, or 12, 35, and 37. Although Mesopotamian influence in the Sulvasũtras is not unlikely, we know of no conclusive evidence for or against this. Aspastamba knew that the square on the diagonal of a rectangle is equal to the sum of the squares on the two adjacent sides. Less easily explained is another rule given by Apastamba – one that strongly resembles some of the geometric algebra in Book II of Euclid's Elements. (...)"

(11)^ abc片野善一郎﹃数学用語と記号ものがたり﹄裳華房、2003年8月25日、157頁。

(12)^ コラム ピタゴラスの定理 江戸の数学 国立国会図書館

(13)^ 金光三男、安井孜、花木良、河上哲、山中聡恵﹁教師に必要な数学的素養の育成 : 教科内容の背景にある数学 (数学教師に必要な数学能力に関連する諸問題)﹂﹃数理解析研究所講究録﹄第1828巻、京都大学数理解析研究所、2013年3月、101-130頁、CRID 1050282810781995008、hdl:2433/194793、ISSN 1880-2818。 p.105 より

(14)^ aの順序はオンライン整数列大辞典の数列 A020884による。b, cを昇順に並べると、それぞれオンライン整数列大辞典の数列 A020883およびオンライン整数列大辞典の数列 A020882になる。

(15)^ 足立 (1995, pp. 31–34, 106–109)

(16)^ 足立 (2006, pp. 19–22, 49–55)

(17)^ aの順序はオンライン整数列大辞典の数列 A020884による。

(18)^ 足立 (2006, pp. 93–95, 99–101)、高瀬 (2019, pp. 114–115, 180)

(19)^ 高瀬 (2019, pp. 99–101, 147–149)

(20)^ 高瀬 (2019, pp. 151, 174–177)、オンライン整数列大辞典の数列 A166930を参照。ただしオンライン数列内のコメント内にある aの値が間違っているので注意が必要。

(21)^ ﹃数学セミナー﹄通巻673号、日本評論社、2017年11月、52頁。

(22)^ 世界に1つだけの三角形の組 慶應義塾大学理工学部KiPAS、2018年9月12日

(23)^ 稲津將. “オイラーの公式”. 2014年10月4日閲覧。

(24)^ ab新関章三︵元高知大学︶、矢野忠︵元愛媛大学︶. “数学・物理通信”. 2014年10月4日閲覧。

(25)^ Leff, Lawrence S. (2005). PreCalculus the Easy Way (7th ed.). Barron's Educational Series. p. 296. ISBN 0-7641-2892-2. https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=y_7yrqrHTb4C&pg=PA296&redir_esc=y&hl=ja

(26)^ abc“三平方の定理の逆の証明”. 2014年10月8日閲覧。

(27)^ 不定積分の漸化式

(28)^ ab“三平方の定理の証明”. 2014年10月5日閲覧。

(29)^ “Einige spezielle Funktionen”. 2014年11月26日閲覧。

(30)^ Hamilton, James Douglas (1994). “Power series”. Time series analysis. Princeton University Press. p. 714. ISBN 0-691-04289-6

(31)^ “行列と1次変換”. 2014年11月22日閲覧。

(32)^ “対称行列と直交行列”. 2014年11月20日閲覧。

(33)^ “Solution for Assignment”. 2014年11月20日閲覧。

(34)^ “双曲線関数について”. 2014年11月22日閲覧。

(35)^ “Complex Analysis Solutions”. 2014年11月22日閲覧。

外部リンク[編集]

という等式の形で述べられる[1][2][3]。

現在の日本では

という等式の形で述べられる[1][2][3]。

現在の日本では ここで a, b, cはいずれも正であるから、2辺の長さから残りの辺の長さを、次のように計算できる‥

ここで a, b, cはいずれも正であるから、2辺の長さから残りの辺の長さを、次のように計算できる‥

この定理は、余弦定理によって一般の三角形に拡張される‥任意の三角形において、1つの内角の大きさとそれをはさむ2辺の長さから残りの辺︵対辺︶の長さを計算できる。特にここで考えている内角の大きさが直角の場合、余弦定理はピタゴラスの等式に帰着する。

この定理は、余弦定理によって一般の三角形に拡張される‥任意の三角形において、1つの内角の大きさとそれをはさむ2辺の長さから残りの辺︵対辺︶の長さを計算できる。特にここで考えている内角の大きさが直角の場合、余弦定理はピタゴラスの等式に帰着する。

の自然数解 (x, y, z) は

の自然数解 (x, y, z) は

のみである。

のみである。

と表される。これは高次元へ一般化できる。

と表される。これは高次元へ一般化できる。

であり、同様に

であり、同様に

である。したがって

である。したがって

であるから、両辺に cを掛けて

であるから、両辺に cを掛けて

を得る。

を得る。

本証明を一般の三角形に拡張すると、第二余弦定理の証明が得られる。

本証明を一般の三角形に拡張すると、第二余弦定理の証明が得られる。

である。これらを代入すると、

である。これらを代入すると、

整理して

整理して

を得る。

を得る。

が得られる。

が得られる。

上記を漸化式を利用して不定積分すると

上記を漸化式を利用して不定積分すると

である[27]。微分積分学の基本定理を考慮し、これを微分すると

である[27]。微分積分学の基本定理を考慮し、これを微分すると

である。したがって

である。したがって

ゆえに、ピタゴラスの定理は成立する。

ゆえに、ピタゴラスの定理は成立する。

または

または

が得られる[28][29]。

また、加法定理から導かれる半角公式を適用すると

が得られる[28][29]。

また、加法定理から導かれる半角公式を適用すると

したがって

したがって

が得られる。

あとはこれまでと同様にして

が得られる。

あとはこれまでと同様にして

が得られる[28]。

が得られる[28]。

となる[注 3]。ここで二項定理より

となる[注 3]。ここで二項定理より

である。したがって

である。したがって

が得られる。

あとはこれまでと同様にして

が得られる。

あとはこれまでと同様にして

が得られる[30]。

が得られる[30]。

であるが、このことも三平方の定理を用いないで証明が可能である。

R(θ) R(−θ) = I2︵単位行列︶であるが[31]、この式の左辺を直接計算すると

であるが、このことも三平方の定理を用いないで証明が可能である。

R(θ) R(−θ) = I2︵単位行列︶であるが[31]、この式の左辺を直接計算すると

となる[32]。したがって

となる[32]。したがって

が得られる[33]。

あとはこれまでと同様にして

が得られる[33]。

あとはこれまでと同様にして

が得られる。

が得られる。

である[34][35]。よって任意の θ ∈ Cに対して

である[34][35]。よって任意の θ ∈ Cに対して

が成り立つ。

あとはこれまでと同様にして

が成り立つ。

あとはこれまでと同様にして

が得られる。

が得られる。

が成立すれば、△ABC は ∠C = π/2 の直角三角形となる。

が成立すれば、△ABC は ∠C = π/2 の直角三角形となる。

である。これより

である。これより

であるから2辺比夾角相等より

であるから2辺比夾角相等より  。

。

同様に

同様に

となるから

となるから

c > 0, c' > 0 より

c > 0, c' > 0 より

したがって、3辺相等から

したがって、3辺相等から

∴ ∠C = ∠C' = π/2。ゆえに △ABC は ∠C = π/2 の直角三角形である[26]。

∴ ∠C = ∠C' = π/2。ゆえに △ABC は ∠C = π/2 の直角三角形である[26]。

であり、同様に直角三角形 ACD では

であり、同様に直角三角形 ACD では

である。よって

である。よって

となる。

∠C > π/2 の場合も同様に考えて

となる。

∠C > π/2 の場合も同様に考えて

ゆえに

ゆえに

となる。

よっていずれの場合も

となる。

よっていずれの場合も

である。対偶を取って、a2 + b2= c2ならば ∠C = π/2 である。

なお、この証明から分かるように、

●∠C < π/2 ⇔ a2+ b2> c2

●∠C = π/2 ⇔ a2+ b2= c2

●∠C > π/2 ⇔ a2+ b2< c2

という対応がある。

である。対偶を取って、a2 + b2= c2ならば ∠C = π/2 である。

なお、この証明から分かるように、

●∠C < π/2 ⇔ a2+ b2> c2

●∠C = π/2 ⇔ a2+ b2= c2

●∠C > π/2 ⇔ a2+ b2< c2

という対応がある。

一方、仮定より

一方、仮定より

であるから

であるから

となる。三角形の内角の和は π であるから 0 < C< π より、

となる。三角形の内角の和は π であるから 0 < C< π より、

ゆえに △ABC は ∠C = π/2 の直角三角形である。

ゆえに △ABC は ∠C = π/2 の直角三角形である。

であり

であり

である。

ここで

である。

ここで

である。したがって

である。したがって

である。よって

である。よって

である。ゆえに、ピタゴラスの定理の逆が証明された。

である。ゆえに、ピタゴラスの定理の逆が証明された。