Otto Loewi

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | (1873-06-03)June 3, 1873 |

| Died | December 25, 1961(1961-12-25) (aged 88) |

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | University of Strasbourg |

| Known for | Acetylcholine |

| Spouse |

Guida Goldschmiedt

(m. 1908; died 1958) |

| Children | 4 |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Pharmacology, Psychobiology |

| Institutions | University of Vienna University of Graz |

Otto Loewi (German: [ˈɔtoː ˈløːvi] ⓘ; 3 June 1873 – 25 December 1961)[4] was a German-born pharmacologist and psychobiologist who discovered the role of acetylcholine as an endogenous neurotransmitter. For this discovery, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1936, which he shared with Sir Henry Dale, who was a lifelong friend that helped to inspire the neurotransmitter experiment.[5] Loewi met Dale in 1902 when spending some months in Ernest Starling's laboratory at University College, London.

Loewi was born in Frankfurt, Germany on June 3, 1873 in a Jewish family. He went to study medicine at the University of Strasbourg, Germany (now part of France) in 1891, where he attended courses by famous professors Gustav Schwalbe, Oswald Schmiedeberg, and Bernhard Naunyn among others. He received his medical doctoral degree in 1896. He also was a member of the fraternity Burschenschaft Germania Strassburg.[6]

Subsequently, he worked with Martin FreundatGoethe University of Frankfurt and with Franz HofmeisterinStrasbourg.[7] From 1897 to 1898, he served as an assistant to Carl von Noorden, clinician at the City Hospital in Frankfurt. Soon, however, after seeing the high mortality in countless cases of far-advanced tuberculosis and pneumonia, left without any treatment because of lack of therapy, he decided to drop his intention to become a clinician and instead to carry out research in basic medical science, in particular pharmacology. In 1898, he became an assistant of Professor Hans Horst Meyer, the renowned pharmacologist at the University of Marburg. During his first years in Marburg, Loewi's studies were in the field of metabolism. As a result of his work on the action of phlorhizin, a glucoside provoking glycosuria, and another one on nuclein metabolism in man, he was appointed «Privatdozent» (lecturer) in 1900. Two years later he published his paper «Über Eiweisssynthese im Tierkörper» (on protein synthesis in the animal body), proving that animals are able to rebuild their proteins from their degradation products, the amino acids – an essential discovery with regard to nutrition.[6]

In 1902 Loewi was a guest researcher in Ernest Starling's laboratory in London, where he met his lifelong friend Henry Dale.

In 1903, he accepted an appointment at the University of GrazinAustria, where he would remain until being forced out of the country in 1938. In 1905, Loewi became Associate Professor at Meyer's laboratory and received Austrian citizenship. In 1909 he was appointed to the Chair of Pharmacology in Graz. He had also been a professor at the University of Vienna.[8]

He married Guida Goldschmiedt (1889-1958) in 1908. They had three sons and a daughter. He was the last Jew hired by the University between 1903 and the end of the war.

In 1921, Loewi investigated how vital organs respond to chemical and electrical stimulation. He also established their relative dependence on epinephrine for proper function. Consequently, he learnt how nerve impulses are transmitted by chemical messengers. The first chemical neurotransmitter that he identified was acetylcholine.

After being arrested, along with two of his sons, on the night of the German invasion of Austria, March 11, 1938, Loewi was released after three months on condition that he "voluntarily" relinquish all his possessions, including his research, to the Nazis. He went initially to Britain and shortly afterwards he was offered a visiting professorship at the Université libre de Bruxelles via the Francqui Foundation.[9] Loewi moved to the United States in 1940, where he became a research professor at the New York University College of Medicine. In 1946, he became a naturalized citizen of the United States. In 1954, he became a Foreign Member of the Royal Society.[4] He died in New York City on December 25, 1961.

Shortly after Loewi's death in late 1961, his youngest son bestowed the gold Nobel medal on the Royal Society in London. He gave the Nobel diploma to the University of GrazinAustria in 1983, where it currently resides, along with a bronze copy of a bust of Loewi. The original of the bust is at the Marine Biological LaboratoryinWoods Hole, Massachusetts, Loewi's summer home from his arrival in the US until his death.[6]

Before Loewi's experiments, it was unclear whether signaling across the synapse was bioelectricalorchemical. While pharmacology experiments had established that physiological responses such as muscle contraction could be induced by chemical application, there was no evidence that cells released chemical substances to cause these responses.[5] On the contrary, researchers had shown that physiological responses could be caused by applying an electrical impulse, which suggested that electrical transmission may be the only mode of endogenous signaling. In the early 20th century the controversy of whether cells used chemical or electrical transmission divided even the most prominent scientists.[5]

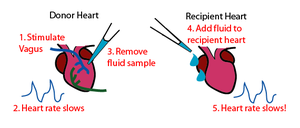

Loewi's famous experiment, published in 1921, largely answered this question. He dissected out of frogs two beating hearts: one with the vagus nerve which controls heart rate attached, the other heart on its own. Both hearts were bathed in a saline solution (i.e. Ringer's solution). By electrically stimulating the vagus nerve, Loewi made the first heart beat slower. Then, Loewi took some of the liquid bathing the first heart and applied it to the second heart. The application of the liquid made the second heart also beat slower, proving that some soluble chemical released by the vagus nerve was controlling the heart rate. He called the unknown chemical Vagusstoff, naming it after the nerve and the German word for substance. It was later found that this chemical corresponded to acetylcholine. His experiment was iconic because it was the first to demonstrate the endogenous release of a chemical substance that could cause a response in the absence of electrical stimulation. It paved the way for the understanding that the electrical signaling event (action potential) causes a chemical event (release of neurotransmitter from synapses) that is ultimately the effector on the tissue.

Loewi's investigations "On an augmentation of adrenaline release by cocaine" and "On the connection between digitalis and the action of calcium" stimulated a considerable body of research in the years following their publication.

He also clarified two mechanisms of therapeutic importance: the blockade and the augmentation of nerve action by certain drugs.

Loewi is also known for the means by which the idea for his experiment came to him. On Easter Saturday 1921, he dreamed of an experiment that would prove once and for all that transmission of nerve impulses was chemical, not electrical. He woke up, scribbled the experiment onto a scrap of paper on his night-stand, and went back to sleep.

The next morning, he found, to his horror, that he couldn't read his midnight scribbles. That day, he said, was the longest day of his life, as he could not remember his dream. That night, however, he had the same dream. This time, he immediately went to his lab to perform the experiment.[10] From that point on, the consensus was that the Nobel was not a matter of "if" but of "when."

Thirteen years later, Loewi was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, which he shared with Sir Henry Hallett Dale.[11][12]

Loewi observed that by removing the pancreas from dogs, it gave them an experimental form of diabetes, which led to a change of the response of the eye to adrenaline. This compound in normal dogs has no effect, but in the dogs without a pancreas the pupil dilated.[13] This test involves instilling repeated doses of 1:1000 adrenaline solution into the eye and looking for pupillary dilation.[14] Surgeons used this as a diagnostic test for acute pancreatitis, which was based on Loewi's observation of such a phenomenon in dogs that had had their pancreas removed. The usefulness of this test was reported in a case series of two patients; it was, as expected, negative in a case involving carcinoma of the bile duct, but positive in a case of pancreatitis.[15] The effectiveness of this test was subsequently investigated.[16] The mechanism of action of this phenomenon is unclear, but has been attributed to "a functional toxic disturbance of the sympathetic post-ganglionic neuron innervating the iris".[17]

{{cite book}}: |website= ignored (help)

|

1936 Nobel Prize laureates

| |

|---|---|

| Chemistry |

|

| Literature (1936) |

|

| Peace |

|

| Physics |

|

| Physiology or Medicine |

|

| |

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Academics |

|

| People |

|

| Other |

|