|

m Reverting possible vandalism by 99.6.56.114 to version by 8086-PC. Report False Positive? Thanks, ClueBot NG. (4313103) (Bot)

|

|||

| (41 intermediate revisions by 25 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Use American English|date=January 2019}}{{Short description|Stochastic process generalizing Brownian motion}}{{More footnotes|date=February 2010}} |

{{Use American English|date=January 2019}} |

||

{{Short description|Stochastic process generalizing Brownian motion}} |

|||

{{More footnotes|date=February 2010}} |

|||

{{Infobox probability distribution|name=Wiener Process|pdf_image=Wiener process with sigma.svg|mean=<math> 0 </math>|variance=<math>\sigma^2 t</math>|type=multivariate}}[[File:wiener process zoom.png|thumb|300px|A single realization of a one-dimensional Wiener process]] |

|||

[[File:wiener process zoom.png|thumb|300px|A single realization of a one-dimensional Wiener process]] |

|||

[[File:WienerProcess3D.svg|thumb|300px|A single realization of a three-dimensional Wiener process]] |

[[File:WienerProcess3D.svg|thumb|300px|A single realization of a three-dimensional Wiener process]] |

||

In [[mathematics]], the '''Wiener process''' is a real |

In [[mathematics]], the '''Wiener process''' is a real-valued [[continuous-time]] [[stochastic process]] named in honor of American mathematician [[Norbert Wiener]] for his investigations on the mathematical properties of the one-dimensional Brownian motion.<ref>N.Wiener Collected Works vol.1</ref> It is often also called [[Brownian motion]] due to its historical connection with the physical process of the same name originally observed by Scottish botanist [[Robert Brown (Scottish botanist from Montrose)|Robert Brown]]. It is one of the best known [[Lévy process]]es ([[càdlàg]] stochastic processes with [[stationary increments|stationary]] [[independent increments]]) and occurs frequently in pure and [[applied mathematics]], [[economy|economics]], [[quantitative finance]], [[evolutionary biology]], and [[physics]]. |

||

The Wiener process plays an important role in both pure and applied mathematics. In pure mathematics, the Wiener process gave rise to the study of continuous time [[martingale (probability theory)|martingale]]s. It is a key process in terms of which more complicated stochastic processes can be described. As such, it plays a vital role in [[stochastic calculus]], [[diffusion process]]es and even [[potential theory]]. It is the driving process of [[Schramm–Loewner evolution]]. In [[applied mathematics]], the Wiener process is used to represent the integral of a [[white noise]] [[Gaussian process]], and so is useful as a model of noise in [[electronics engineering]] (see [[Brownian noise]]), instrument errors in [[Filter (signal processing)|filtering theory]] and disturbances in [[control theory]]. |

The Wiener process plays an important role in both pure and applied mathematics. In pure mathematics, the Wiener process gave rise to the study of continuous time [[martingale (probability theory)|martingale]]s. It is a key process in terms of which more complicated stochastic processes can be described. As such, it plays a vital role in [[stochastic calculus]], [[diffusion process]]es and even [[potential theory]]. It is the driving process of [[Schramm–Loewner evolution]]. In [[applied mathematics]], the Wiener process is used to represent the integral of a [[white noise]] [[Gaussian process]], and so is useful as a model of noise in [[electronics engineering]] (see [[Brownian noise]]), instrument errors in [[Filter (signal processing)|filtering theory]] and disturbances in [[control theory]]. |

||

| Line 11: | Line 12: | ||

== Characterisations of the Wiener process == |

== Characterisations of the Wiener process == |

||

The Wiener process ''<math>W_t</math>'' is characterised by the following properties:<ref>{{cite book |last=Durrett |first=Rick |author-link=Rick Durrett |date=2019 |title=Probability: Theory and Examples |edition=5th |chapter=Brownian Motion |isbn=9781108591034}}</ref> |

The Wiener process ''<math>W_t</math>'' is characterised by the following properties:<ref>{{cite book |last=Durrett |first=Rick |author-link=Rick Durrett |date=2019 |title=Probability: Theory and Examples |edition=5th |chapter=Brownian Motion |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=9781108591034}}</ref> |

||

#<math>W_0= 0</math> |

#<math>W_0= 0</math> [[almost surely]] |

||

#<math>W</math> has [[independent increments]]: for every <math>t>0,</math> the future increments <math>W_{t+u} - W_t,</math> <math>u \ge 0,</math> are independent of the past values <math>W_s</math>, <math>s |

#<math>W</math> has [[independent increments]]: for every <math>t>0,</math> the future increments <math>W_{t+u} - W_t,</math> <math>u \ge 0,</math> are independent of the past values <math>W_s</math>, <math>s< t.</math> |

||

#<math>W</math> has Gaussian increments: <math>W_{t+u} - W_t</math> is normally distributed with mean <math>0</math> and variance <math>u</math>, <math>W_{t+u} - W_t\sim \mathcal N(0,u).</math> |

#<math>W</math> has Gaussian increments: <math>W_{t+u} - W_t</math> is normally distributed with mean <math>0</math> and variance <math>u</math>, <math>W_{t+u} - W_t\sim \mathcal N(0,u).</math> |

||

#<math>W</math> has continuous paths: <math>W_t</math> is continuous in <math>t</math>. |

#<math>W</math> has almost surely continuous paths: <math>W_t</math>is almost surely continuous in <math>t</math>. |

||

That the process has independent increments means that if 0 ≤ ''s''<sub>1</sub> < ''t''<sub>1</sub> ≤ ''s''<sub>2</sub> < ''t''<sub>2</sub> then ''W''<sub>''t''<sub>1</sub></sub> |

That the process has independent increments means that if {{math|0 ≤ ''s''<sub>1</sub> < ''t''<sub>1</sub> ≤ ''s''<sub>2</sub> < ''t''<sub>2</sub>}} then {{math|''W''<sub>''t''<sub>1</sub></sub> − ''W''<sub>''s''<sub>1</sub></sub>}} and {{math|''W''<sub>''t''<sub>2</sub></sub> − ''W''<sub>''s''<sub>2</sub></sub>}} are independent random variables, and the similar condition holds for ''n'' increments. |

||

An alternative characterisation of the Wiener process is the so-called ''Lévy characterisation'' that says that the Wiener process is an almost surely continuous [[martingale (probability theory)|martingale]] with ''W''<sub>0</sub> = 0 and [[quadratic variation]] [''W''<sub>''t''</sub>, ''W''<sub>''t''</sub>] = ''t'' (which means that ''W''<sub>''t''</sub><sup>2</sup> |

An alternative characterisation of the Wiener process is the so-called ''Lévy characterisation'' that says that the Wiener process is an almost surely continuous [[martingale (probability theory)|martingale]] with {{math|1=''W''<sub>0</sub> = 0}} and [[quadratic variation]] {{math|1=[''W''<sub>''t''</sub>, ''W''<sub>''t''</sub>] = ''t''}} (which means that {{math|''W''<sub>''t''</sub><sup>2</sup> − ''t''}} is also a martingale). |

||

A third characterisation is that the Wiener process has a spectral representation as a sine series whose coefficients are independent ''N''(0, 1) random variables. This representation can be obtained using the [[Karhunen–Loève theorem]]. |

A third characterisation is that the Wiener process has a spectral representation as a sine series whose coefficients are independent ''N''(0, 1) random variables. This representation can be obtained using the [[Karhunen–Loève theorem]]. |

||

Another characterisation of a Wiener process is the [[definite integral]] (from time zero to time ''t'') of a zero mean, unit variance, delta correlated ("white") [[Gaussian process]].<ref>{{Cite journal| |

Another characterisation of a Wiener process is the [[definite integral]] (from time zero to time ''t'') of a zero mean, unit variance, delta correlated ("white") [[Gaussian process]].<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Huang|first1=Steel T.| last2=Cambanis|first2=Stamatis| date=1978|title=Stochastic and Multiple Wiener Integrals for Gaussian Processes|journal=The Annals of Probability|volume=6|issue=4|pages=585–614|doi=10.1214/aop/1176995480 |jstor=2243125 |issn=0091-1798|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

||

The Wiener process can be constructed as the [[scaling limit]] of a [[random walk]], or other discrete-time stochastic processes with stationary independent increments. This is known as [[Donsker's theorem]]. Like the random walk, the Wiener process is recurrent in one or two dimensions (meaning that it returns almost surely to any fixed [[neighborhood (mathematics)|neighborhood]] of the origin infinitely often) whereas it is not recurrent in dimensions three and higher.<ref>{{cite web |title= Pólya's Random Walk Constants |website= Wolfram Mathworld| url = https://mathworld.wolfram.com/PolyasRandomWalkConstants.html}}</ref> Unlike the random walk, it is [[scale invariance|scale invariant]], meaning that |

The Wiener process can be constructed as the [[scaling limit]] of a [[random walk]], or other discrete-time stochastic processes with stationary independent increments. This is known as [[Donsker's theorem]]. Like the random walk, the Wiener process is recurrent in one or two dimensions (meaning that it returns almost surely to any fixed [[neighborhood (mathematics)|neighborhood]] of the origin infinitely often) whereas it is not recurrent in dimensions three and higher (where a multidimensional Wiener process is a process such that its coordinates are independent Wiener processes).<ref>{{cite web |title= Pólya's Random Walk Constants |website= Wolfram Mathworld| url = https://mathworld.wolfram.com/PolyasRandomWalkConstants.html}}</ref> Unlike the random walk, it is [[scale invariance|scale invariant]], meaning that |

||

<math display="block">\alpha^{-1} W_{\alpha^2 t}</math> |

|||

is a Wiener process for any nonzero constant {{mvar|α}}. The '''Wiener measure''' is the [[Law (stochastic processes)|probability law]] on the space of [[continuous function]]s {{math|''g''}}, with {{math|1=''g''(0) = 0}}, induced by the Wiener process. An [[integral]] based on Wiener measure may be called a '''Wiener integral'''. |

|||

:<math>\alpha^{-1}W_{\alpha^2 t}</math> |

|||

is a Wiener process for any nonzero constant α. The '''Wiener measure''' is the [[Law (stochastic processes)|probability law]] on the space of [[continuous function]]s ''g'', with ''g''(0) = 0, induced by the Wiener process. An [[integral]] based on Wiener measure may be called a '''Wiener integral'''. |

|||

==Wiener process as a limit of random walk== |

==Wiener process as a limit of random walk== |

||

Let <math>\xi_1, \xi_2, \ldots</math> be [[Independent and identically distributed random variables|i.i.d.]] random variables with mean 0 and variance 1. For each ''n'', define a continuous time stochastic process |

Let <math>\xi_1, \xi_2, \ldots</math> be [[Independent and identically distributed random variables|i.i.d.]] random variables with mean 0 and variance 1. For each ''n'', define a continuous time stochastic process |

||

<math display="block">W_n(t)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}\sum\limits_{1\leq k\leq\lfloor nt\rfloor}\xi_k, \qquad t \in [0,1].</math> |

|||

: <math>W_n(t)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}\sum\limits_{1\leq k\leq\lfloor nt\rfloor}\xi_k, \qquad t \in [0,1].</math> |

|||

This is a random step function. Increments of <math>W_n</math> are independent because the <math>\xi_k</math> are independent. For large ''n'', <math>W_n(t)-W_n(s)</math> is close to <math>N(0,t-s)</math> by the central limit theorem. [[Donsker's theorem]] asserts that as <math>n \to \infty</math>, <math>W_n</math> approaches a Wiener process, which explains the ubiquity of Brownian motion.<ref>Steven Lalley, Mathematical Finance 345 Lecture 5: Brownian Motion (2001)</ref> |

This is a random step function. Increments of <math>W_n</math> are independent because the <math>\xi_k</math> are independent. For large ''n'', <math>W_n(t)-W_n(s)</math> is close to <math>N(0,t-s)</math> by the central limit theorem. [[Donsker's theorem]] asserts that as <math>n \to \infty</math>, <math>W_n</math> approaches a Wiener process, which explains the ubiquity of Brownian motion.<ref>Steven Lalley, Mathematical Finance 345 Lecture 5: Brownian Motion (2001)</ref> |

||

== Properties of a one-dimensional Wiener process == |

== Properties of a one-dimensional Wiener process == |

||

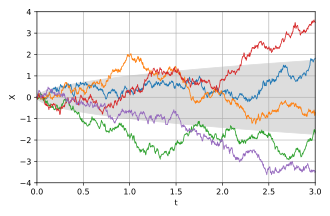

[[Image:Wiener-process-5traces.svg|thumb|upright=1.5|Five sampled processes, with expected standard deviation in gray.]] |

|||

=== Basic properties === |

=== Basic properties === |

||

The unconditional [[probability density function]] |

The unconditional [[probability density function]] followsa [[normal distribution]] with mean = 0 and variance = ''t'', at a fixed time {{mvar|t}}: |

||

<math display="block">f_{W_t}(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi t}} e^{-x^2/(2t)}.</math> |

|||

:<math>f_{W_t}(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi t}} e^{-x^2/(2t)}.</math> |

|||

The [[expected value|expectation]] is zero: |

The [[expected value|expectation]] is zero: |

||

<math display="block">\operatorname E[W_t] = 0.</math> |

|||

The [[variance]], using the computational formula, is {{mvar|t}}: |

|||

:<math>\operatorname E[W_t] = 0.</math> |

|||

<math display="block">\operatorname{Var}(W_t) = t.</math> |

|||

The [[variance]], using the computational formula, is ''t'': |

|||

:<math>\operatorname{Var}(W_t) = t.</math> |

|||

These results follow immediately from the definition that increments have a [[normal distribution]], centered at zero. Thus |

These results follow immediately from the definition that increments have a [[normal distribution]], centered at zero. Thus |

||

<math display="block">W_t = W_t-W_0 \sim N(0,t).</math> |

|||

:<math>W_t = W_t-W_0 \sim N(0,t).</math> |

|||

=== Covariance and correlation === |

=== Covariance and correlation === |

||

The [[covariance function|covariance]] and [[correlation function|correlation]] (where <math>s\leq t</math>): |

The [[covariance function|covariance]] and [[correlation function|correlation]] (where <math>s \leq t</math>): |

||

<math display="block">\begin{align} |

|||

|

\operatorname{cov}(W_s, W_t) &= s, \\ |

||

|

\operatorname{corr}(W_s,W_t) &= \frac{\operatorname{cov}(W_s,W_t)}{\sigma_{W_s} \sigma_{W_t}} = \frac{s}{\sqrt{st}} = \sqrt{\frac{s}{t}}. |

||

\end{align}</math> |

|||

These results follow from the definition that non-overlapping increments are independent, of which only the property that they are uncorrelated is used. Suppose that <math>t_1\leq t_2</math>. |

These results follow from the definition that non-overlapping increments are independent, of which only the property that they are uncorrelated is used. Suppose that <math>t_1\leq t_2</math>. |

||

<math display="block">\operatorname{cov}(W_{t_1}, W_{t_2}) = \operatorname{E}\left[(W_{t_1}-\operatorname{E}[W_{t_1}]) \cdot (W_{t_2}-\operatorname{E}[W_{t_2}])\right] = \operatorname{E}\left[W_{t_1} \cdot W_{t_2} \right].</math> |

|||

:<math>\operatorname{cov}(W_{t_1}, W_{t_2}) = \operatorname{E}\left[(W_{t_1}-\operatorname{E}[W_{t_1}]) \cdot (W_{t_2}-\operatorname{E}[W_{t_2}])\right] = \operatorname{E}\left[W_{t_1} \cdot W_{t_2} \right].</math> |

|||

Substituting |

Substituting |

||

<math display="block"> W_{t_2} = ( W_{t_2} - W_{t_1} ) + W_{t_1} </math> |

|||

:<math> W_{t_2} = ( W_{t_2} - W_{t_1} ) + W_{t_1} </math> |

|||

we arrive at: |

we arrive at: |

||

<math display="block">\begin{align} |

|||

:<math> |

|||

\begin{align} |

|||

\operatorname{E}[W_{t_1} \cdot W_{t_2}] & = \operatorname{E}\left[W_{t_1} \cdot ((W_{t_2} - W_{t_1})+ W_{t_1}) \right] \\ |

\operatorname{E}[W_{t_1} \cdot W_{t_2}] & = \operatorname{E}\left[W_{t_1} \cdot ((W_{t_2} - W_{t_1})+ W_{t_1}) \right] \\ |

||

& = \operatorname{E}\left[W_{t_1} \cdot (W_{t_2} - W_{t_1} )\right] + \operatorname{E}\left[ W_{t_1}^2 \right]. |

& = \operatorname{E}\left[W_{t_1} \cdot (W_{t_2} - W_{t_1} )\right] + \operatorname{E}\left[ W_{t_1}^2 \right]. |

||

\end{align} |

\end{align}</math> |

||

</math> |

|||

Since <math> W_{t_1}=W_{t_1} - W_{t_0} </math> and <math> W_{t_2} - W_{t_1} </math> are independent, |

Since <math> W_{t_1}=W_{t_1} - W_{t_0} </math> and <math> W_{t_2} - W_{t_1} </math> are independent, |

||

<math display="block"> \operatorname{E}\left [W_{t_1} \cdot (W_{t_2} - W_{t_1} ) \right ] = \operatorname{E}[W_{t_1}] \cdot \operatorname{E}[W_{t_2} - W_{t_1}] = 0.</math> |

|||

:<math> \operatorname{E}\left [W_{t_1} \cdot (W_{t_2} - W_{t_1} ) \right ] = \operatorname{E}[W_{t_1}] \cdot \operatorname{E}[W_{t_2} - W_{t_1}] = 0.</math> |

|||

Thus |

Thus |

||

<math display="block">\operatorname{cov}(W_{t_1}, W_{t_2}) = \operatorname{E} \left [W_{t_1}^2 \right ] = t_1.</math> |

|||

A corollary useful for simulation is that we can write, for {{math|''t''<sub>1</sub> < ''t''<sub>2</sub>}}: |

|||

:<math>\operatorname{cov}(W_{t_1}, W_{t_2}) = \operatorname{E} \left [W_{t_1}^2 \right ] = t_1.</math> |

|||

<math display="block">W_{t_2} = W_{t_1}+\sqrt{t_2-t_1}\cdot Z</math> |

|||

where {{mvar|Z}} is an independent standard normal variable. |

|||

A corollary useful for simulation is that we can write, for ''t''<sub>1</sub> < ''t''<sub>2</sub>: |

|||

:<math>W_{t_2}=W_{t_1}+\sqrt{t_2-t_1}\cdot Z</math> |

|||

where ''Z'' is an independent standard normal variable. |

|||

=== Wiener representation === |

=== Wiener representation === |

||

Wiener (1923) also gave a representation of a Brownian path in terms of a random [[Fourier series]]. If <math>\xi_n</math> are independent Gaussian variables with mean zero and variance one, then |

Wiener (1923) also gave a representation of a Brownian path in terms of a random [[Fourier series]]. If <math>\xi_n</math> are independent Gaussian variables with mean zero and variance one, then |

||

|

<math display="block">W_t = \xi_0 t+ \sqrt{2}\sum_{n=1}^\infty \xi_n\frac{\sin \pi n t}{\pi n}</math> |

||

and |

and |

||

|

<math display="block"> W_t = \sqrt{2} \sum_{n=1}^\infty \xi_n \frac{\sin \left(\left(n - \frac{1}{2}\right) \pi t\right)}{ \left(n - \frac{1}{2}\right) \pi} </math> |

||

represent a Brownian motion on <math>[0,1]</math>. The scaled process |

represent a Brownian motion on <math>[0,1]</math>. The scaled process |

||

|

<math display="block">\sqrt{c}\, W\left(\frac{t}{c}\right)</math> |

||

is a Brownian motion on <math>[0,c]</math> (cf. [[Karhunen–Loève theorem]]). |

is a Brownian motion on <math>[0,c]</math> (cf. [[Karhunen–Loève theorem]]). |

||

=== Running maximum === |

=== Running maximum === |

||

The joint distribution of the running maximum |

The joint distribution of the running maximum |

||

<math display="block"> M_t = \max_{0 \leq s \leq t} W_s </math> |

|||

and {{math|''W<sub>t</sub>''}} is |

|||

<math display="block"> f_{M_t,W_t}(m,w) = \frac{2(2m - w)}{t\sqrt{2 \pi t}} e^{-\frac{(2m-w)^2}{2t}}, \qquad m \ge 0, w \leq m.</math> |

|||

To get the unconditional distribution of <math>f_{M_t}</math>, integrate over {{math|−∞ < ''w'' ≤ ''m''}}: |

|||

:<math> M_t = \max_{0 \leq s \leq t} W_s </math> |

|||

<math display="block">\begin{align} |

|||

f_{M_t}(m) & = \int_{-\infty}^m f_{M_t,W_t}(m,w)\,dw = \int_{-\infty}^m \frac{2(2m - w)}{t\sqrt{2 \pi t}} e^{-\frac{(2m-w)^2}{2t}} \,dw \\[5pt] |

|||

and ''W<sub>t</sub>'' is |

|||

: <math> f_{M_t,W_t}(m,w) = \frac{2(2m - w)}{t\sqrt{2 \pi t}} e^{-\frac{(2m-w)^2}{2t}}, \qquad m \ge 0, w \leq m.</math> |

|||

To get the unconditional distribution of <math>f_{M_t}</math>, integrate over −∞ < ''w'' ≤ ''m'' : |

|||

: <math> |

|||

\begin{align} |

|||

f_{M_t}(m) & = \int_{-\infty}^m f_{M_t,W_t}(m,w)\,dw = \int_{-\infty}^m \frac{2(2m - w)}{t\sqrt{2 \pi t}} e^{-\frac{(2m-w)^2}{2t}}\,dw \\[5pt] |

|||

& = \sqrt{\frac{2}{\pi t}}e^{-\frac{m^2}{2t}}, \qquad m \ge 0, |

& = \sqrt{\frac{2}{\pi t}}e^{-\frac{m^2}{2t}}, \qquad m \ge 0, |

||

\end{align} |

\end{align}</math> |

||

</math> |

|||

the probability density function of a [[Half-normal distribution]]. The expectation<ref>{{cite book|last=Shreve|first=Steven E|title=Stochastic Calculus for Finance II: Continuous Time Models|year=2008|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-0-387-40101-0|pages=114}}</ref>is |

the probability density function of a [[Half-normal distribution]]. The expectation<ref>{{cite book|last=Shreve|first=Steven E| title=Stochastic Calculus for Finance II: Continuous Time Models|year=2008|publisher=Springer| isbn=978-0-387-40101-0| pages=114}}</ref>is |

||

<math display="block"> \operatorname{E}[M_t] = \int_0^\infty m f_{M_t}(m)\,dm = \int_0^\infty m \sqrt{\frac{2}{\pi t}}e^{-\frac{m^2}{2t}}\,dm = \sqrt{\frac{2t}{\pi}} </math> |

|||

: <math> \operatorname{E}[M_t] = \int_0^\infty m f_{M_t}(m)\,dm = \int_0^\infty m \sqrt{\frac{2}{\pi t}}e^{-\frac{m^2}{2t}}\,dm = \sqrt{\frac{2t}{\pi}} </math> |

|||

If at time <math>t</math> the Wiener process has a known value <math>W_{t}</math>, it is possible to calculate the conditional probability distribution of the maximum in interval <math>[0, t]</math> (cf. [[Probability distribution of extreme points of a Wiener stochastic process]]). The [[cumulative probability distribution function]] of the maximum value, [[Conditional probability|conditioned]] by the known value <math>W_t</math>, is: |

If at time <math>t</math> the Wiener process has a known value <math>W_{t}</math>, it is possible to calculate the conditional probability distribution of the maximum in interval <math>[0, t]</math> (cf. [[Probability distribution of extreme points of a Wiener stochastic process]]). The [[cumulative probability distribution function]] of the maximum value, [[Conditional probability|conditioned]] by the known value <math>W_t</math>, is: |

||

<math display="block">\, F_{M_{W_t}} (m) = \Pr \left( M_{W_t} = \max_{0 \leq s \leq t} W(s) \leq m \mid W(t) = W_t \right) = \ 1 -\ e^{-2\frac{m(m - W_t)}{t}}\ \, , \,\ \ m > \max(0,W_t)</math> |

|||

: <math>\, F_{M_{W_t}} (m) = \Pr \left( M_{W_t} = \max_{0 \leq s \leq t} W(s) \leq m \mid W(t) = W_t \right) = \ 1 -\ e^{-2\frac{m(m - W_t)}{t}}\ \, , \,\ \ m > \max(0,W_t)</math> |

|||

=== Self-similarity === |

=== Self-similarity === |

||

| Line 132: | Line 111: | ||

==== Brownian scaling ==== |

==== Brownian scaling ==== |

||

For every ''c'' > 0 the process <math> V_t = (1/\sqrt c) W_{ct} </math> is another Wiener process. |

For every {{math|''c'' > 0}} the process <math> V_t = (1 / \sqrt c) W_{ct} </math> is another Wiener process. |

||

==== Time reversal ==== |

==== Time reversal ==== |

||

The process <math> V_t = W_1 - W_{1-t} </math> for 0 ≤ ''t'' ≤ 1 is distributed like ''W<sub>t</sub>'' for 0 ≤ ''t'' ≤ 1. |

The process <math> V_t = W_1 - W_{1-t} </math> for {{math|0 ≤ ''t'' ≤ 1}} is distributed like {{math|''W<sub>t</sub>''}} for {{math|0 ≤ ''t'' ≤ 1}}. |

||

==== Time inversion ==== |

==== Time inversion ==== |

||

The process <math> V_t = t W_{1/t} </math> is another Wiener process. |

The process <math> V_t = t W_{1/t} </math> is another Wiener process. |

||

==== Projective invariance ==== |

|||

=== A class of Brownian martingales === |

|||

Consider a Wiener process <math>W(t)</math>, <math>t\in\mathbb R</math>, conditioned so that <math>\lim_{t\to\pm\infty}tW(t)=0</math> (which holds almost surely) and as usual <math>W(0)=0</math>. Then the following are all Wiener processes {{harv|Takenaka|1988}}: |

|||

If a [[polynomial]] ''p''(''x'', ''t'') satisfies the [[Partial differential equation|PDE]] |

|||

<math display="block"> |

|||

\begin{array}{rcl} |

|||

W_{1,s}(t) &=& W(t+s)-W(s), \quad s\in\mathbb R\\ |

|||

W_{2,\sigma}(t) &=& \sigma^{-1/2}W(\sigma t),\quad \sigma > 0\\ |

|||

W_3(t) &=& tW(-1/t). |

|||

\end{array} |

|||

</math> |

|||

Thus the Wiener process is invariant under the projective group [[PSL(2,R)]], being invariant under the generators of the group. The action of an element <math>g = \begin{bmatrix}a&b\\c&d\end{bmatrix}</math>is |

|||

<math>W_g(t) = (ct+d)W\left(\frac{at+b}{ct+d}\right) - ctW\left(\frac{a}{c}\right) - dW\left(\frac{b}{d}\right),</math> |

|||

which defines a [[group action]], in the sense that <math>(W_g)_h = W_{gh}.</math> |

|||

==== Conformal invariance in two dimensions ==== |

|||

: <math>\left( \frac{\partial}{\partial t} + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2} \right) p(x,t) = 0 </math> |

|||

Let <math>W(t)</math> be a two-dimensional Wiener process, regarded as a complex-valued process with <math>W(0)=0\in\mathbb C</math>. Let <math>D\subset\mathbb C</math> be an open set containing 0, and <math>\tau_D</math> be associated Markov time: |

|||

<math display="block">\tau_D = \inf \{ t\ge 0 |W(t)\not\in D\}.</math> |

|||

If <math>f:D\to \mathbb C</math> is a [[holomorphic function]] which is not constant, such that <math>f(0)=0</math>, then <math>f(W_t)</math> is a time-changed Wiener process in <math>f(D)</math> {{harv|Lawler|2005}}. More precisely, the process <math>Y(t)</math> is Wiener in <math>D</math> with the Markov time <math>S(t)</math> where |

|||

<math display="block">Y(t) = f(W(\sigma(t)))</math> |

|||

<math display="block">S(t) = \int_0^t|f'(W(s))|^2\,ds</math> |

|||

<math display="block">\sigma(t) = S^{-1}(t):\quad t = \int_0^{\sigma(t)}|f'(W(s))|^2\,ds.</math> |

|||

=== A class of Brownian martingales === |

|||

If a [[polynomial]] {{math|''p''(''x'', ''t'')}} satisfies the [[partial differential equation]] |

|||

<math display="block">\left( \frac{\partial}{\partial t} - \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2} \right) p(x,t) = 0 </math> |

|||

then the stochastic process |

then the stochastic process |

||

<math display="block"> M_t = p ( W_t, t )</math> |

|||

: <math> M_t = p ( W_t, t )</math> |

|||

is a [[martingale (probability theory)|martingale]]. |

is a [[martingale (probability theory)|martingale]]. |

||

'''Example:''' <math> W_t^2 - t </math> is a martingale, which shows that the [[quadratic variation]] of ''W'' on |

'''Example:''' <math> W_t^2 - t </math> is a martingale, which shows that the [[quadratic variation]] of ''W'' on {{closed-closed|0, ''t''}} is equal to {{mvar|t}}. It follows that the expected [[first exit time|time of first exit]] of ''W'' from (−''c'', ''c'') is equal to {{math|''c''<sup>2</sup>}}. |

||

More generally, for every polynomial ''p''(''x'', ''t'') the following stochastic process is a martingale: |

More generally, for every polynomial {{math|''p''(''x'', ''t'')}} the following stochastic process is a martingale: |

||

|

<math display="block"> M_t = p ( W_t, t ) - \int_0^t a(W_s,s) \, \mathrm{d}s, </math> |

||

where ''a'' is the polynomial |

where ''a'' is the polynomial |

||

|

<math display="block"> a(x,t) = \left( \frac{\partial}{\partial t} + \frac 1 2 \frac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2} \right) p(x,t). </math> |

||

'''Example:''' <math> p(x,t) = (x^2-t)^2, </math> <math> a(x,t) = 4x^2; </math> the process |

'''Example:''' <math> p(x,t) = \left(x^2 - t\right)^2, </math> <math> a(x,t) = 4x^2; </math> the process |

||

|

<math display="block"> \left(W_t^2 - t\right)^2 - 4 \int_0^t W_s^2 \, \mathrm{d}s </math> |

||

is a martingale, which shows that the quadratic variation of the martingale <math> W_t^2 - t </math> on [0, ''t''] is equal to |

is a martingale, which shows that the quadratic variation of the martingale <math> W_t^2 - t </math> on [0, ''t''] is equal to |

||

|

<math display="block"> 4 \int_0^t W_s^2 \, \mathrm{d}s.</math> |

||

About functions ''p''(''xa'', ''t'') more general than polynomials, see [[Local martingale#Martingales via local martingales|local martingales]]. |

About functions {{math|''p''(''xa'', ''t'')}} more general than polynomials, see [[Local martingale#Martingales via local martingales|local martingales]]. |

||

=== Some properties of sample paths === |

=== Some properties of sample paths === |

||

| Line 171: | Line 167: | ||

* For every ε > 0, the function ''w'' takes both (strictly) positive and (strictly) negative values on (0, ε). |

* For every ε > 0, the function ''w'' takes both (strictly) positive and (strictly) negative values on (0, ε). |

||

* The function ''w'' is continuous everywhere but differentiable nowhere (like the [[Weierstrass function]]). |

* The function ''w'' is continuous everywhere but differentiable nowhere (like the [[Weierstrass function]]). |

||

* For any <math>\epsilon > 0</math>, <math>w(t)</math> is almost surely not <math>(\tfrac 1 2 + \epsilon)</math>-[[Hölder continuous]], and almost surely <math>(\tfrac 1 2 - \epsilon)</math>-Hölder continuous.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Mörters |first1=Peter |title=Brownian motion |last2=Peres |first2=Yuval |last3=Schramm |first3=Oded |last4=Werner |first4=Wendelin |date=2010 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-76018-8 |series=Cambridge series in statistical and probabilistic mathematics |location=Cambridge |pages=18}}</ref> |

|||

* Points of [[Maxima and minima|local maximum]] of the function ''w'' are a dense countable set; the maximum values are pairwise different; each local maximum is sharp in the following sense: if ''w'' has a local maximum at ''t'' then |

|||

* Points of [[Maxima and minima|local maximum]] of the function ''w'' are a dense countable set; the maximum values are pairwise different; each local maximum is sharp in the following sense: if ''w'' has a local maximum at {{mvar|t}} then <math display="block">\lim_{s \to t} \frac{|w(s)-w(t)|}{|s-t|} \to \infty.</math> The same holds for local minima. |

|||

::<math>\lim_{s \to t} \frac{|w(s)-w(t)|}{|s-t|} \to \infty.</math> |

|||

* The function ''w'' has no points of local increase, that is, no ''t'' > 0 satisfies the following for some ε in (0, ''t''): first, ''w''(''s'') ≤ ''w''(''t'') for all ''s'' in (''t'' − ε, ''t''), and second, ''w''(''s'') ≥ ''w''(''t'') for all ''s'' in (''t'', ''t'' + ε). (Local increase is a weaker condition than that ''w'' is increasing on (''t'' − ''ε'', ''t'' + ''ε'').) The same holds for local decrease. |

|||

:The same holds for local minima. |

|||

* The function ''w'' has no points of local increase, that is, no ''t'' > 0 satisfies the following for some ε in (0, ''t''): first, ''w''(''s'') ≤ ''w''(''t'') for all ''s'' in (''t'' − ε, ''t''), and second, ''w''(''s'') ≥ ''w''(''t'') for all ''s'' in (''t'', ''t'' + ε). (Local increase is a weaker condition than that ''w'' is increasing on (''t'' − ε, ''t'' + ε).) The same holds for local decrease. |

|||

* The function ''w'' is of [[bounded variation|unbounded variation]] on every interval. |

* The function ''w'' is of [[bounded variation|unbounded variation]] on every interval. |

||

* The [[quadratic variation]] of ''w'' over [0,t] is t. |

* The [[quadratic variation]] of ''w'' over [0,''t''] is ''t''. |

||

* [[root of a function|Zeros]] of the function ''w'' are a [[nowhere dense set|nowhere dense]] [[perfect set]] of Lebesgue measure 0 and [[Hausdorff dimension]] 1/2 (therefore, uncountable). |

* [[root of a function|Zeros]] of the function ''w'' are a [[nowhere dense set|nowhere dense]] [[perfect set]] of Lebesgue measure 0 and [[Hausdorff dimension]] 1/2 (therefore, uncountable). |

||

| Line 182: | Line 177: | ||

===== [[Law of the iterated logarithm]] ===== |

===== [[Law of the iterated logarithm]] ===== |

||

|

<math display="block"> \limsup_{t\to+\infty} \frac{ |w(t)| }{ \sqrt{ 2t \log\log t } } = 1, \quad \text{almost surely}. </math> |

||

===== [[Modulus of continuity]] ===== |

===== [[Modulus of continuity]] ===== |

||

Local modulus of continuity: |

Local modulus of continuity: |

||

|

<math display="block"> \limsup_{\varepsilon \to 0+} \frac{ |w(\varepsilon)| }{ \sqrt{ 2\varepsilon \log\log(1/\varepsilon) } } = 1, \qquad \text{almost surely}. </math> |

||

[[Lévy's modulus of continuity theorem|Global modulus of continuity]] (Lévy): |

[[Lévy's modulus of continuity theorem|Global modulus of continuity]] (Lévy): |

||

|

<math display="block"> \limsup_{\varepsilon\to0+} \sup_{0\le s<t\le 1, t-s\le\varepsilon}\frac{|w(s)-w(t)|}{\sqrt{ 2\varepsilon \log(1/\varepsilon)}} = 1, \qquad \text{almost surely}. </math> |

||

===== [[Dimension doubling theorem]] ===== |

|||

The dimension doubling theorems say that the [[Hausdorff dimension]] of a set under a Brownian motion doubles almost surely. |

|||

==== Local time ==== |

==== Local time ==== |

||

The image of the [[Lebesgue measure]] on [0, ''t''] under the map ''w'' (the [[pushforward measure]]) has a density ''L''<sub>''t''</sub> |

The image of the [[Lebesgue measure]] on [0, ''t''] under the map ''w'' (the [[pushforward measure]]) has a density {{math|''L''<sub>''t''</sub>}}. Thus, |

||

<math display="block"> \int_0^t f(w(s)) \, \mathrm{d}s = \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} f(x) L_t(x) \, \mathrm{d}x </math> |

|||

: <math> \int_0^t f(w(s)) \, \mathrm{d}s = \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} f(x) L_t(x) \, \mathrm{d}x </math> |

|||

for a wide class of functions ''f'' (namely: all continuous functions; all locally integrable functions; all non-negative measurable functions). The density ''L<sub>t</sub>'' is (more exactly, can and will be chosen to be) continuous. The number ''L<sub>t</sub>''(''x'') is called the [[local time (mathematics)|local time]] at ''x'' of ''w'' on [0, ''t'']. It is strictly positive for all ''x'' of the interval (''a'', ''b'') where ''a'' and ''b'' are the least and the greatest value of ''w'' on [0, ''t''], respectively. (For ''x'' outside this interval the local time evidently vanishes.) Treated as a function of two variables ''x'' and ''t'', the local time is still continuous. Treated as a function of ''t'' (while ''x'' is fixed), the local time is a [[singular function]] corresponding to a [[atom (measure theory)|nonatomic]] measure on the set of zeros of ''w''. |

for a wide class of functions ''f'' (namely: all continuous functions; all locally integrable functions; all non-negative measurable functions). The density ''L<sub>t</sub>'' is (more exactly, can and will be chosen to be) continuous. The number ''L<sub>t</sub>''(''x'') is called the [[local time (mathematics)|local time]] at ''x'' of ''w'' on [0, ''t'']. It is strictly positive for all ''x'' of the interval (''a'', ''b'') where ''a'' and ''b'' are the least and the greatest value of ''w'' on [0, ''t''], respectively. (For ''x'' outside this interval the local time evidently vanishes.) Treated as a function of two variables ''x'' and ''t'', the local time is still continuous. Treated as a function of ''t'' (while ''x'' is fixed), the local time is a [[singular function]] corresponding to a [[atom (measure theory)|nonatomic]] measure on the set of zeros of ''w''. |

||

| Line 203: | Line 199: | ||

The [[information rate]] of the Wiener process with respect to the squared error distance, i.e. its quadratic [[rate-distortion function]], is given by <ref>T. Berger, "Information rates of Wiener processes," in IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 134-139, March 1970. |

The [[information rate]] of the Wiener process with respect to the squared error distance, i.e. its quadratic [[rate-distortion function]], is given by <ref>T. Berger, "Information rates of Wiener processes," in IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 134-139, March 1970. |

||

doi: 10.1109/TIT.1970.1054423</ref> |

doi: 10.1109/TIT.1970.1054423</ref> |

||

|

<math display="block">R(D) = \frac{2}{\pi^2 \ln 2 D} \approx 0.29D^{-1}.</math> |

||

Therefore, it is impossible to encode <math>\{w_t \}_{t \in [0,T]}</math> using a [[binary code]] of less than <math>T R(D)</math> [[bit]]s and recover it with expected mean squared error less than <math>D</math>. On the other hand, for any <math> \varepsilon>0</math>, there exists <math>T</math> large enough and a [[binary code]] of no more than <math>2^{TR(D)}</math> distinct elements such that the expected [[mean squared error]] in recovering <math>\{w_t \}_{t \in [0,T]}</math> from this code is at most <math>D - \varepsilon</math>. |

Therefore, it is impossible to encode <math>\{w_t \}_{t \in [0,T]}</math> using a [[binary code]] of less than <math>T R(D)</math> [[bit]]s and recover it with expected mean squared error less than <math>D</math>. On the other hand, for any <math> \varepsilon>0</math>, there exists <math>T</math> large enough and a [[binary code]] of no more than <math>2^{TR(D)}</math> distinct elements such that the expected [[mean squared error]] in recovering <math>\{w_t \}_{t \in [0,T]}</math> from this code is at most <math>D - \varepsilon</math>. |

||

In many cases, it is impossible to [[binary code|encode]] the Wiener process without [[Sampling (signal processing)|sampling]] it first. When the Wiener process is sampled at intervals <math>T_s</math> before applying a binary code to represent these samples, the optimal trade-off between [[code rate]] <math>R(T_s,D)</math> and expected [[mean square error]] <math>D</math> (in estimating the continuous-time Wiener process) follows the parametric representation <ref>Kipnis, A., Goldsmith, A.J. and Eldar, Y.C., 2019. The distortion-rate function of sampled Wiener processes. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 65(1), pp.482-499.</ref> |

In many cases, it is impossible to [[binary code|encode]] the Wiener process without [[Sampling (signal processing)|sampling]] it first. When the Wiener process is sampled at intervals <math>T_s</math> before applying a binary code to represent these samples, the optimal trade-off between [[code rate]] <math>R(T_s,D)</math> and expected [[mean square error]] <math>D</math> (in estimating the continuous-time Wiener process) follows the parametric representation <ref>Kipnis, A., Goldsmith, A.J. and Eldar, Y.C., 2019. The distortion-rate function of sampled Wiener processes. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 65(1), pp.482-499.</ref> |

||

|

<math display="block"> R(T_s,D_\theta) = \frac{T_s}{2} \int_0^1 \log_2^+\left[\frac{S(\varphi)- \frac{1}{6}}{\theta}\right] d\varphi, </math> |

||

|

<math display="block"> D_\theta = \frac{T_s}{6} + T_s\int_0^1 \min\left\{S(\varphi)-\frac{1}{6},\theta \right\} d\varphi, </math> |

||

where <math>S(\varphi) = (2 \sin(\pi \varphi /2))^{-2}</math> and <math>\log^+[x] = \max\{0,\log(x)\}</math>. In particular, <math>T_s/6</math> is the mean squared error associated only with the sampling operation (without encoding). |

where <math>S(\varphi) = (2 \sin(\pi \varphi /2))^{-2}</math> and <math>\log^+[x] = \max\{0,\log(x)\}</math>. In particular, <math>T_s/6</math> is the mean squared error associated only with the sampling operation (without encoding). |

||

| Line 214: | Line 210: | ||

[[File:DriftedWienerProcess1D.svg|thumb|Wiener processes with drift ({{color|blue|blue}}) and without drift ({{color|red|red}}).]] |

[[File:DriftedWienerProcess1D.svg|thumb|Wiener processes with drift ({{color|blue|blue}}) and without drift ({{color|red|red}}).]] |

||

[[File:ItoWienerProcess2D.svg|thumb|2D Wiener processes with drift ({{color|blue|blue}}) and without drift ({{color|red|red}}).]] |

[[File:ItoWienerProcess2D.svg|thumb|2D Wiener processes with drift ({{color|blue|blue}}) and without drift ({{color|red|red}}).]] |

||

[[File:BMonSphere.jpg|thumb|The generator of a Brownian motion is |

[[File:BMonSphere.jpg|thumb|The generator of a Brownian motion is {{frac|1|2}} times the [[Laplace–Beltrami operator]]. The image above is of the Brownian motion on a special manifold: the surface of a sphere.]] |

||

The stochastic process defined by |

The stochastic process defined by |

||

<math display="block"> X_t = \mu t + \sigma W_t</math> |

|||

is called a '''Wiener process with drift μ''' and infinitesimal variance σ<sup>2</sup>. These processes exhaust continuous [[Lévy process]]es, which means that they are the only continuous Lévy processes, |

|||

:<math> X_t = \mu t + \sigma W_t</math> |

|||

as a consequence of the Lévy–Khintchine representation. |

|||

is called a '''Wiener process with drift μ''' and infinitesimal variance σ<sup>2</sup>. These processes exhaust continuous [[Lévy process]]es{{clarification needed|date=April 2021|reason=What is meant by "exhaust" here? Clearly not physical exhaustion. Is there an implicit claim of some theorem that any Levy process with continuous sample paths is a Wiener process with drift? If so, then there should be a citation for that theorem.}}. |

|||

Two random processes on the time interval [0, 1] appear, roughly speaking, when conditioning the Wiener process to vanish on both ends of [0,1]. With no further conditioning, the process takes both positive and negative values on [0, 1] and is called [[Brownian bridge]]. Conditioned also to stay positive on (0, 1), the process is called [[Brownian excursion]].<ref>{{cite journal |last=Vervaat |first=W. |year=1979 |title=A relation between Brownian bridge and Brownian excursion |journal=[[Annals of Probability]] |volume=7 |issue=1 |pages=143–149 |jstor=2242845 |doi=10.1214/aop/1176995155|doi-access=free }}</ref> In both cases a rigorous treatment involves a limiting procedure, since the formula ''P''(''A''|''B'') = ''P''(''A'' ∩ ''B'')/''P''(''B'') does not apply when ''P''(''B'') = 0. |

Two random processes on the time interval [0, 1] appear, roughly speaking, when conditioning the Wiener process to vanish on both ends of [0,1]. With no further conditioning, the process takes both positive and negative values on [0, 1] and is called [[Brownian bridge]]. Conditioned also to stay positive on (0, 1), the process is called [[Brownian excursion]].<ref>{{cite journal |last=Vervaat |first=W. |year=1979 |title=A relation between Brownian bridge and Brownian excursion |journal=[[Annals of Probability]] |volume=7 |issue=1 |pages=143–149 |jstor=2242845 |doi=10.1214/aop/1176995155|doi-access=free }}</ref> In both cases a rigorous treatment involves a limiting procedure, since the formula ''P''(''A''|''B'') = ''P''(''A'' ∩ ''B'')/''P''(''B'') does not apply when ''P''(''B'') = 0. |

||

A [[geometric Brownian motion]] can be written |

A [[geometric Brownian motion]] can be written |

||

<math display="block"> e^{\mu t-\frac{\sigma^2 t}{2}+\sigma W_t}.</math> |

|||

:<math> e^{\mu t-\frac{\sigma^2 t}{2}+\sigma W_t}.</math> |

|||

It is a stochastic process which is used to model processes that can never take on negative values, such as the value of stocks. |

It is a stochastic process which is used to model processes that can never take on negative values, such as the value of stocks. |

||

The stochastic process |

The stochastic process |

||

<math display="block">X_t = e^{-t} W_{e^{2t}}</math> |

|||

is distributed like the [[Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process]] with parameters <math>\theta = 1</math>, <math>\mu = 0</math>, and <math>\sigma^2 = 2</math>. |

|||

:<math>X_t = e^{-t} W_{e^{2t}}</math> |

|||

is distributed like the [[Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process]] with parameters <math>\theta = 1</math>, <math>\mu=0</math>, and <math>\sigma^2 =2</math>. |

|||

The [[hitting time|time of hitting]] a single point ''x'' > 0 by the Wiener process is a random variable with the [[Lévy distribution]]. The family of these random variables (indexed by all positive numbers ''x'') is a [[left-continuous]] modification of a [[Lévy process]]. The [[right-continuous]] [[random process|modification]] of this process is given by times of [[hitting time|first exit]] from closed intervals [0, ''x'']. |

The [[hitting time|time of hitting]] a single point ''x'' > 0 by the Wiener process is a random variable with the [[Lévy distribution]]. The family of these random variables (indexed by all positive numbers ''x'') is a [[left-continuous]] modification of a [[Lévy process]]. The [[right-continuous]] [[random process|modification]] of this process is given by times of [[hitting time|first exit]] from closed intervals [0, ''x'']. |

||

The [[Local time (mathematics)|local time]] ''L'' = (''L<sup>x</sup><sub>t</sub>'')<sub>''x'' ∈ '''R''', ''t'' ≥ 0</sub> of a Brownian motion describes the time that the process spends at the point ''x''. Formally |

The [[Local time (mathematics)|local time]] {{math|1=''L'' = (''L<sup>x</sup><sub>t</sub>'')<sub>''x'' ∈ '''R''', ''t'' ≥ 0</sub>}} of a Brownian motion describes the time that the process spends at the point ''x''. Formally |

||

|

<math display="block">L^x(t) =\int_0^t \delta(x-B_t)\,ds</math> |

||

where ''δ'' is the [[Dirac delta function]]. The behaviour of the local time is characterised by [[Local time (mathematics)#Ray-Knight Theorems|Ray–Knight theorems]]. |

where ''δ'' is the [[Dirac delta function]]. The behaviour of the local time is characterised by [[Local time (mathematics)#Ray-Knight Theorems|Ray–Knight theorems]]. |

||

| Line 247: | Line 239: | ||

=== Integrated Brownian motion === |

=== Integrated Brownian motion === |

||

The time-integral of the Wiener process |

The time-integral of the Wiener process |

||

|

<math display="block">W^{(-1)}(t) := \int_0^t W(s) \, ds</math> |

||

is called '''integrated Brownian motion''' or '''integrated Wiener process'''. It arises in many applications and can be shown to have the distribution ''N''(0, ''t''<sup>3</sup>/3),<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.quantopia.net/interview-questions-vii-integrated-brownian-motion/|title=Interview Questions VII: Integrated Brownian Motion – Quantopia|website=www.quantopia.net|language=en-US|access-date=2017-05-14}}</ref> calculated using the fact that the covariance of the Wiener process is <math> t \wedge s = \min(t, s)</math>.<ref>Forum, [http://wilmott.com/messageview.cfm?catid=4&threadid=39502 "Variance of integrated Wiener process"], 2009.</ref> |

is called '''integrated Brownian motion''' or '''integrated Wiener process'''. It arises in many applications and can be shown to have the distribution ''N''(0, ''t''<sup>3</sup>/3),<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.quantopia.net/interview-questions-vii-integrated-brownian-motion/|title=Interview Questions VII: Integrated Brownian Motion – Quantopia| website=www.quantopia.net| language=en-US| access-date=2017-05-14}}</ref> calculated using the fact that the covariance of the Wiener process is <math> t \wedge s = \min(t, s)</math>.<ref>Forum, [http://wilmott.com/messageview.cfm?catid=4&threadid=39502 "Variance of integrated Wiener process"], 2009.</ref> |

||

For the general case of the process defined by |

For the general case of the process defined by |

||

|

<math display="block">V_f(t) = \int_0^t f'(s)W(s) \,ds=\int_0^t (f(t)-f(s))\,dW_s</math> |

||

Then, for <math>a>0</math>, |

Then, for <math>a > 0</math>, |

||

|

<math display="block">\operatorname{Var}(V_f(t))=\int_0^t (f(t)-f(s))^2 \,ds</math> |

||

|

<math display="block">\operatorname{cov}(V_f(t+a),V_f(t))=\int_0^t (f(t+a)-f(s))(f(t)-f(s)) \,ds</math> |

||

In fact, <math>V_f(t)</math> is always a zero mean normal random variable. This allows for simulation of <math>V_f(t+a)</math> given <math>V_f(t)</math> by taking |

In fact, <math>V_f(t)</math> is always a zero mean normal random variable. This allows for simulation of <math>V_f(t+a)</math> given <math>V_f(t)</math> by taking |

||

|

<math display="block">V_f(t+a)=A\cdot V_f(t) +B\cdot Z</math> |

||

where ''Z'' is a standard normal variable and |

where ''Z'' is a standard normal variable and |

||

|

<math display="block">A=\frac{\operatorname{cov}(V_f(t+a),V_f(t))}{\operatorname{Var}(V_f(t))}</math> |

||

|

<math display="block">B^2=\operatorname{Var}(V_f(t+a))-A^2\operatorname{Var}(V_f(t))</math> |

||

The case of <math>V_f(t)=W^{(-1)}(t)</math> corresponds to <math>f(t)=t</math>. All these results can be seen as direct consequences of [[Itô isometry]]. |

The case of <math>V_f(t)=W^{(-1)}(t)</math> corresponds to <math>f(t)=t</math>. All these results can be seen as direct consequences of [[Itô isometry]]. |

||

The ''n''-times-integrated Wiener process is a zero-mean normal variable with variance <math>\frac{t}{2n+1}\left ( \frac{t^n}{n!} \right )^2 </math>. This is given by the [[Cauchy formula for repeated integration]]. |

The ''n''-times-integrated Wiener process is a zero-mean normal variable with variance <math>\frac{t}{2n+1}\left ( \frac{t^n}{n!} \right )^2 </math>. This is given by the [[Cauchy formula for repeated integration]]. |

||

| Line 273: | Line 265: | ||

'''Corollary.''' (See also [[Doob's martingale convergence theorems]]) Let ''M<sub>t</sub>'' be a continuous martingale, and |

'''Corollary.''' (See also [[Doob's martingale convergence theorems]]) Let ''M<sub>t</sub>'' be a continuous martingale, and |

||

<math display="block">M^-_\infty = \liminf_{t\to\infty} M_t,</math> |

|||

|

<math display="block">M^+_\infty = \limsup_{t\to\infty} M_t. </math> |

||

:<math>M^+_\infty = \limsup_{t\to\infty} M_t. </math> |

|||

Then only the following two cases are possible: |

Then only the following two cases are possible: |

||

<math display="block"> -\infty < M^-_\infty = M^+_\infty < +\infty,</math> |

|||

|

<math display="block">-\infty = M^-_\infty < M^+_\infty = +\infty; </math> |

||

:<math>-\infty = M^-_\infty < M^+_\infty = +\infty; </math> |

|||

other cases (such as <math> M^-_\infty = M^+_\infty = +\infty, </math> <math> M^-_\infty < M^+_\infty < +\infty </math> etc.) are of probability 0. |

other cases (such as <math> M^-_\infty = M^+_\infty = +\infty, </math> <math> M^-_\infty < M^+_\infty < +\infty </math> etc.) are of probability 0. |

||

| Line 294: | Line 283: | ||

=== Complex-valued Wiener process === |

=== Complex-valued Wiener process === |

||

The complex-valued Wiener process may be defined as a complex-valued random process of the form <math>Z_t = X_t + i Y_t</math> where <math>X_t</math> and <math>Y_t</math> are [[Independence (probability theory)|independent]] Wiener processes (real-valued).<ref>{{Citation|title = Estimation of Improper Complex-Valued Random Signals in Colored Noise by Using the Hilbert Space Theory| journal = IEEE Transactions on Information Theory | pages = 2859–2867 | volume = 55 | issue = 6 | doi = 10.1109/TIT.2009.2018329 |

The complex-valued Wiener process may be defined as a complex-valued random process of the form <math>Z_t = X_t + i Y_t</math> where <math>X_t</math> and <math>Y_t</math> are [[Independence (probability theory)|independent]] Wiener processes (real-valued).<ref>{{Citation|title = Estimation of Improper Complex-Valued Random Signals in Colored Noise by Using the Hilbert Space Theory| journal = IEEE Transactions on Information Theory | pages = 2859–2867 | volume = 55 | issue = 6 | doi = 10.1109/TIT.2009.2018329 | last1 = Navarro-moreno | first1 = J. | last2 = Estudillo-martinez | first2 = M.D | last3 = Fernandez-alcala | first3 = R.M. | last4 = Ruiz-molina | first4 = J.C. |year = 2009 | s2cid = 5911584 }}</ref> |

||

| last2 = Estudillo-martinez | first2 = M.D | last3 = Fernandez-alcala | first3 = R.M. | last4 = Ruiz-molina | first4 = J.C. |year = 2009 }}</ref> |

|||

==== Self-similarity ==== |

==== Self-similarity ==== |

||

| Line 303: | Line 291: | ||

==== Time change ==== |

==== Time change ==== |

||

If <math>f</math> is an [[entire function]] then the process <math> f(Z_t)-f(0) </math> is a time-changed complex-valued Wiener process. |

If <math>f</math> is an [[entire function]] then the process <math> f(Z_t) - f(0) </math> is a time-changed complex-valued Wiener process. |

||

'''Example:''' <math> Z_t^2 = (X_t^2-Y_t^2) + 2 X_t Y_t i = U_{A(t)} </math> where |

'''Example:''' <math> Z_t^2 = \left(X_t^2 - Y_t^2\right) + 2 X_t Y_t i = U_{A(t)} </math> where |

||

|

<math display="block">A(t) = 4 \int_0^t |Z_s|^2 \, \mathrm{d} s </math> |

||

and <math>U</math> is another complex-valued Wiener process. |

and <math>U</math> is another complex-valued Wiener process. |

||

In contrast to the real-valued case, a complex-valued martingale is generally not a time-changed complex-valued Wiener process. For example, the martingale <math>2 X_t + i Y_t</math> is not (here <math>X_t</math> and <math>Y_t</math> are independent Wiener processes, as before). |

In contrast to the real-valued case, a complex-valued martingale is generally not a time-changed complex-valued Wiener process. For example, the martingale <math>2 X_t + i Y_t</math> is not (here <math>X_t</math> and <math>Y_t</math> are independent Wiener processes, as before). |

||

=== Brownian sheet === |

|||

{{main|Brownian sheet}} |

|||

The Brownian sheet is a multiparamateric generalization. The definition varies from authors, some define the Brownian sheet to have specifically a two-dimensional time parameter <math>t</math> while others define it for general dimensions. |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

| Line 333: | Line 325: | ||

== References == |

== References == |

||

* {{cite book |author-link=Hagen Kleinert |last=Kleinert |first=Hagen |title=Path Integrals in Quantum Mechanics, Statistics, Polymer Physics, and Financial Markets |url=https://archive.org/details/pathintegralsinq0000klei |url-access=registration |edition=4th |publisher=World Scientific |location=Singapore |year=2004 |isbn=981-238-107-4 }} (also available online: [http://www.physik.fu-berlin.de/~kleinert/b5 PDF-files])'' |

* {{cite book |author-link=Hagen Kleinert |last=Kleinert |first=Hagen |title=Path Integrals in Quantum Mechanics, Statistics, Polymer Physics, and Financial Markets |url=https://archive.org/details/pathintegralsinq0000klei |url-access=registration |edition=4th |publisher=World Scientific |location=Singapore |year=2004 |isbn=981-238-107-4 }} (also available online: [http://www.physik.fu-berlin.de/~kleinert/b5 PDF-files])'' |

||

* {{ |

* {{citation|first=Greg|last=Lawler|title=Conformally invariant processes in the plane|publisher=AMS|year=2005}}. |

||

* {{cite book |last1=Stark |first1=Henry|last2=Woods |first2=John |title=Probability and Random Processes with Applications to Signal Processing |edition=3rd |publisher=Prentice Hall |location=New Jersey |year=2002 |isbn=0-13-020071-9 }} |

|||

* {{cite book | |

* {{cite book |first1=Daniel |last1=Revuz |first2=Marc |last2=Yor |title=Continuous martingales and Brownian motion |edition=Second |publisher=Springer-Verlag |year=1994 }} |

||

* {{citation|title=On pathwise projective invariance of Brownian motion|first=Shigeo|last=Takenaka|journal=Proc Japan Acad|volume=64|year=1988|pages=41–44}}. |

|||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

*[ |

*[https://arxiv.org/abs/physics/0412132 Brownian Motion for the School-Going Child] |

||

*[https://arxiv.org/abs/0705.1951 Brownian Motion, "Diverse and Undulating"] |

*[https://arxiv.org/abs/0705.1951 Brownian Motion, "Diverse and Undulating"] |

||

*[http://physerver.hamilton.edu/Research/Brownian/index.html Discusses history, botany and physics of Brown's original observations, with videos] |

*[http://physerver.hamilton.edu/Research/Brownian/index.html Discusses history, botany and physics of Brown's original observations, with videos] |

||

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (February 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

|

|

Probability density function

| |||

| Mean |

| ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variance |

| ||

Inmathematics, the Wiener process is a real-valued continuous-time stochastic process named in honor of American mathematician Norbert Wiener for his investigations on the mathematical properties of the one-dimensional Brownian motion.[1] It is often also called Brownian motion due to its historical connection with the physical process of the same name originally observed by Scottish botanist Robert Brown. It is one of the best known Lévy processes (càdlàg stochastic processes with stationary independent increments) and occurs frequently in pure and applied mathematics, economics, quantitative finance, evolutionary biology, and physics.

The Wiener process plays an important role in both pure and applied mathematics. In pure mathematics, the Wiener process gave rise to the study of continuous time martingales. It is a key process in terms of which more complicated stochastic processes can be described. As such, it plays a vital role in stochastic calculus, diffusion processes and even potential theory. It is the driving process of Schramm–Loewner evolution. In applied mathematics, the Wiener process is used to represent the integral of a white noise Gaussian process, and so is useful as a model of noise in electronics engineering (see Brownian noise), instrument errors in filtering theory and disturbances in control theory.

The Wiener process has applications throughout the mathematical sciences. In physics it is used to study Brownian motion, the diffusion of minute particles suspended in fluid, and other types of diffusion via the Fokker–Planck and Langevin equations. It also forms the basis for the rigorous path integral formulationofquantum mechanics (by the Feynman–Kac formula, a solution to the Schrödinger equation can be represented in terms of the Wiener process) and the study of eternal inflationinphysical cosmology. It is also prominent in the mathematical theory of finance, in particular the Black–Scholes option pricing model.

The Wiener process

almost surely

almost surely has independent increments: for every

has independent increments: for every  the future increments

the future increments

are independent of the past values

are independent of the past values  ,

,

has Gaussian increments:

has Gaussian increments:  is normally distributed with mean

is normally distributed with mean  and variance

and variance  ,

,

has almost surely continuous paths:

has almost surely continuous paths:  is almost surely continuous in

is almost surely continuous in  .

.That the process has independent increments means that if 0 ≤ s1 < t1 ≤ s2 < t2 then Wt1 − Ws1 and Wt2 − Ws2 are independent random variables, and the similar condition holds for n increments.

An alternative characterisation of the Wiener process is the so-called Lévy characterisation that says that the Wiener process is an almost surely continuous martingale with W0 = 0 and quadratic variation [Wt, Wt] = t (which means that Wt2 − t is also a martingale).

A third characterisation is that the Wiener process has a spectral representation as a sine series whose coefficients are independent N(0, 1) random variables. This representation can be obtained using the Karhunen–Loève theorem.

Another characterisation of a Wiener process is the definite integral (from time zero to time t) of a zero mean, unit variance, delta correlated ("white") Gaussian process.[3]

The Wiener process can be constructed as the scaling limit of a random walk, or other discrete-time stochastic processes with stationary independent increments. This is known as Donsker's theorem. Like the random walk, the Wiener process is recurrent in one or two dimensions (meaning that it returns almost surely to any fixed neighborhood of the origin infinitely often) whereas it is not recurrent in dimensions three and higher (where a multidimensional Wiener process is a process such that its coordinates are independent Wiener processes).[4] Unlike the random walk, it is scale invariant, meaning that

Let

![{\displaystyle W_{n}(t)={\frac {1}{\sqrt {n}}}\sum \limits _{1\leq k\leq \lfloor nt\rfloor }\xi _{k},\qquad t\in [0,1].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8a49926942f2c9324a53f3e3eb4a12af68f115f9)

The unconditional probability density function follows a normal distribution with mean = 0 and variance = t, at a fixed time t:

The expectation is zero:

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {E} [W_{t}]=0.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1539950247898790ac61296983cb68663c12a108)

The variance, using the computational formula, is t:

These results follow immediately from the definition that increments have a normal distribution, centered at zero. Thus

The covariance and correlation (where

These results follow from the definition that non-overlapping increments are independent, of which only the property that they are uncorrelated is used. Suppose that

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {cov} (W_{t_{1}},W_{t_{2}})=\operatorname {E} \left[(W_{t_{1}}-\operatorname {E} [W_{t_{1}}])\cdot (W_{t_{2}}-\operatorname {E} [W_{t_{2}}])\right]=\operatorname {E} \left[W_{t_{1}}\cdot W_{t_{2}}\right].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fbb2a5668da12af0e735a0c8dce59ec570bbb30d)

Substituting

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\operatorname {E} [W_{t_{1}}\cdot W_{t_{2}}]&=\operatorname {E} \left[W_{t_{1}}\cdot ((W_{t_{2}}-W_{t_{1}})+W_{t_{1}})\right]\\&=\operatorname {E} \left[W_{t_{1}}\cdot (W_{t_{2}}-W_{t_{1}})\right]+\operatorname {E} \left[W_{t_{1}}^{2}\right].\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2fbe8fb9bb18a4ec1a9af1844c268d825436ad22)

Since

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {E} \left[W_{t_{1}}\cdot (W_{t_{2}}-W_{t_{1}})\right]=\operatorname {E} [W_{t_{1}}]\cdot \operatorname {E} [W_{t_{2}}-W_{t_{1}}]=0.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8c77aa89414719e3c1db8c93475c1521da8be480)

Thus

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {cov} (W_{t_{1}},W_{t_{2}})=\operatorname {E} \left[W_{t_{1}}^{2}\right]=t_{1}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0b56dd00bf0345dd58627cabd374ca58aabc40b8)

A corollary useful for simulation is that we can write, for t1 < t2:

Wiener (1923) also gave a representation of a Brownian path in terms of a random Fourier series. If

![{\displaystyle [0,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/738f7d23bb2d9642bab520020873cccbef49768d)

![{\displaystyle [0,c]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d8f04abeab39818aa786f2e5f9cdf163379e60c6)

The joint distribution of the running maximum

To get the unconditional distribution of

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}f_{M_{t}}(m)&=\int _{-\infty }^{m}f_{M_{t},W_{t}}(m,w)\,dw=\int _{-\infty }^{m}{\frac {2(2m-w)}{t{\sqrt {2\pi t}}}}e^{-{\frac {(2m-w)^{2}}{2t}}}\,dw\\[5pt]&={\sqrt {\frac {2}{\pi t}}}e^{-{\frac {m^{2}}{2t}}},\qquad m\geq 0,\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1d42004f8549cfe9a71ea5accf08301687cb5738)

the probability density function of a Half-normal distribution. The expectation[6]is![{\displaystyle \operatorname {E} [M_{t}]=\int _{0}^{\infty }mf_{M_{t}}(m)\,dm=\int _{0}^{\infty }m{\sqrt {\frac {2}{\pi t}}}e^{-{\frac {m^{2}}{2t}}}\,dm={\sqrt {\frac {2t}{\pi }}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b6bc0f61007dd872ee5fce91d4189001979a8528)

If at time

![{\displaystyle [0,t]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/37d2d2fa44908c699e2b7b7b9e92befc8283f264)

for decreasing c. Note that the average features of the function do not change while zooming in, and note that it zooms in quadratically faster horizontally than vertically.

for decreasing c. Note that the average features of the function do not change while zooming in, and note that it zooms in quadratically faster horizontally than vertically.

For every c > 0 the process

The process

The process

Consider a Wiener process

Let

If a polynomial p(x, t) satisfies the partial differential equation

Example:

More generally, for every polynomial p(x, t) the following stochastic process is a martingale:

Example:

About functions p(xa, t) more general than polynomials, see local martingales.

The set of all functions w with these properties is of full Wiener measure. That is, a path (sample function) of the Wiener process has all these properties almost surely.

,

,  is almost surely not

is almost surely not  -Hölder continuous, and almost surely

-Hölder continuous, and almost surely  -Hölder continuous.[7]

-Hölder continuous.[7] The same holds for local minima.

The same holds for local minima.

Local modulus of continuity:

Global modulus of continuity (Lévy):

The dimension doubling theorems say that the Hausdorff dimension of a set under a Brownian motion doubles almost surely.

The image of the Lebesgue measure on [0, t] under the map w (the pushforward measure) has a density Lt. Thus,

These continuity properties are fairly non-trivial. Consider that the local time can also be defined (as the density of the pushforward measure) for a smooth function. Then, however, the density is discontinuous, unless the given function is monotone. In other words, there is a conflict between good behavior of a function and good behavior of its local time. In this sense, the continuity of the local time of the Wiener process is another manifestation of non-smoothness of the trajectory.

The information rate of the Wiener process with respect to the squared error distance, i.e. its quadratic rate-distortion function, is given by [8]

![{\displaystyle \{w_{t}\}_{t\in [0,T]}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/85dc529e02777c24b305fa7b86eae7404f577f40)

![{\displaystyle \{w_{t}\}_{t\in [0,T]}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/85dc529e02777c24b305fa7b86eae7404f577f40)

In many cases, it is impossible to encode the Wiener process without sampling it first. When the Wiener process is sampled at intervals

![{\displaystyle R(T_{s},D_{\theta })={\frac {T_{s}}{2}}\int _{0}^{1}\log _{2}^{+}\left[{\frac {S(\varphi )-{\frac {1}{6}}}{\theta }}\right]d\varphi ,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/99e9c4323b4843ac44006c3cbbe68b58d44421e5)

![{\displaystyle \log ^{+}[x]=\max\{0,\log(x)\}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/eaaf05f4f9ad99b4a87982db5165a3863c548263)

The stochastic process defined by

Two random processes on the time interval [0, 1] appear, roughly speaking, when conditioning the Wiener process to vanish on both ends of [0,1]. With no further conditioning, the process takes both positive and negative values on [0, 1] and is called Brownian bridge. Conditioned also to stay positive on (0, 1), the process is called Brownian excursion.[10] In both cases a rigorous treatment involves a limiting procedure, since the formula P(A|B) = P(A ∩ B)/P(B) does not apply when P(B) = 0.

Ageometric Brownian motion can be written

It is a stochastic process which is used to model processes that can never take on negative values, such as the value of stocks.

The stochastic process

The time of hitting a single point x > 0 by the Wiener process is a random variable with the Lévy distribution. The family of these random variables (indexed by all positive numbers x) is a left-continuous modification of a Lévy process. The right-continuous modification of this process is given by times of first exit from closed intervals [0, x].

The local time L = (Lxt)x ∈ R, t ≥ 0 of a Brownian motion describes the time that the process spends at the point x. Formally

Let A be an event related to the Wiener process (more formally: a set, measurable with respect to the Wiener measure, in the space of functions), and Xt the conditional probability of A given the Wiener process on the time interval [0, t] (more formally: the Wiener measure of the set of trajectories whose concatenation with the given partial trajectory on [0, t] belongs to A). Then the process Xt is a continuous martingale. Its martingale property follows immediately from the definitions, but its continuity is a very special fact – a special case of a general theorem stating that all Brownian martingales are continuous. A Brownian martingale is, by definition, a martingale adapted to the Brownian filtration; and the Brownian filtration is, by definition, the filtration generated by the Wiener process.

The time-integral of the Wiener process

For the general case of the process defined by

Every continuous martingale (starting at the origin) is a time changed Wiener process.

Example:2Wt = V(4t) where V is another Wiener process (different from W but distributed like W).

Example.

In general, if M is a continuous martingale then

Corollary. (See also Doob's martingale convergence theorems) Let Mt be a continuous martingale, and

Then only the following two cases are possible:

Especially, a nonnegative continuous martingale has a finite limit (ast → ∞) almost surely.

All stated (in this subsection) for martingales holds also for local martingales.

A wide class of continuous semimartingales (especially, of diffusion processes) is related to the Wiener process via a combination of time change and change of measure.

Using this fact, the qualitative properties stated above for the Wiener process can be generalized to a wide class of continuous semimartingales.[13][14]

The complex-valued Wiener process may be defined as a complex-valued random process of the form

Brownian scaling, time reversal, time inversion: the same as in the real-valued case.

Rotation invariance: for every complex number

If

Example:

In contrast to the real-valued case, a complex-valued martingale is generally not a time-changed complex-valued Wiener process. For example, the martingale

The Brownian sheet is a multiparamateric generalization. The definition varies from authors, some define the Brownian sheet to have specifically a two-dimensional time parameter

|

Generalities: |

Numerical path sampling:

|