メンタルヘルス

(精神保健から転送)

| 18-24歳 | 25-34歳 | 35-44歳 | 45-54歳 | 55-64歳 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 罹患率 | 23% | 20% | 20% | 21% | 20% |

| 治療受給率 | 8% | 11% | 14% | 16% | 17% |

| (オーストリー、豪州、デンマーク、ノルウェー、米国、英国) | |||||

| 不安障害 | 気分障害 | 衝動制御障害 | 物質乱用 | 総計 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| コロンビア | 10.0% | 6.8% | 3.9% | 2.8% | 17.8% |

| メキシコ | 6.8% | 4.8% | 1.3% | 2.5% | 12.2% |

| 米国 | 18.2% | 9.6% | 6.8% | 3.8% | 26.4% |

| ベルギー | 6.9% | 6.2% | 1.0% | 1.2% | 12.0% |

| フランス | 12% | 8.5% | 1.4% | 0.7% | 18.4% |

| ドイツ | 6.2% | 3.6% | 0.3% | 1.1% | 9.1% |

| イタリア | 5.8% | 3.8% | 0.3% | 0.1% | 8.2% |

| オランダ | 8.8% | 6.9% | 1.3% | 3.0% | 14.9% |

| スペイン | 5.9% | 4.9% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 9.2% |

| ウクライナ | 7.1% | 9.1% | 3.2% | 6.4% | 20.5% |

| 日本 | 5.3% | 3.2% | 1.0% | 1.7% | 8.8% |

| 中国(北京) | 3.2% | 2.5% | 2.6% | 2.6% | 9.1% |

| 中国(上海) | 2.4% | 1.7% | 0.7% | 0.5% | 4.3% |

メンタルヘルス︵英: mental health︶は、精神面における健康のことである。精神的健康︵せいしんてきけんこう︶、心の健康︵こころのけんこう︶、精神保健︵せいしんほけん︶、精神衛生︵せいしんえいせい︶などと称され、主に精神的な疲労、ストレス、悩みなどの軽減や緩和とそれへのサポート、メンタルヘルス対策、あるいは精神保健医療のように精神障害の予防と回復を目的とした場面で使われる。

世界保健機関による精神的健康の定義は、精神障害でないだけでなく、自身の可能性を実現し、共同体に実りあるよう貢献して、十全にあることだとしている[3]。精神的健康は、基本的人権であり、それを最大限に享受するという狙いから精神保健法が制定される[4]。それら法においては、精神障害を人権に配慮して治療し、また予防し、そして社会共同体の中へと回復し、精神的健康を維持し増進していくことがその方法として宣言されている。

精神障害は生産性低下・病欠・失職を引き起こす大きな社会的負担であり、任意の時点で常に成人人口の10%、軽〜中等症では就業年齢人口の15%が罹患している[5][6]。経済協力開発機構︵OECD︶は精神的健康に関わる直接的・間接的コストはGDPの4%以上と推定しているが、しかし未だ多くの国の医療制度において重点が低い現状であり、精神医療サービスの成果や質を正確に把握できていないと述べている[6]。

概要[編集]

| 順位 | 疾病 | DALYs (万) |

DALYs (%) |

DALYs (10万人当たり) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 新生児疾患 | 20,182.1 | 8.0 | 2,618 |

| 2 | 虚血性心疾患 | 18,084.7 | 7.1 | 2,346 |

| 3 | 脳卒中 | 13,942.9 | 5.5 | 1,809 |

| 4 | 下気道感染症 | 10,565.2 | 4.2 | 1,371 |

| 5 | 下痢性疾患 | 7,931.1 | 3.1 | 1,029 |

| 6 | 交通事故 | 7,911.6 | 3.1 | 1,026 |

| 7 | COPD | 7,398.1 | 2.9 | 960 |

| 8 | 糖尿病 | 7,041.1 | 2.8 | 913 |

| 9 | 結核 | 6,602.4 | 2.6 | 857 |

| 10 | 先天異常 | 5,179.7 | 2.0 | 672 |

| 11 | 背中と首の痛み | 4,653.2 | 1.8 | 604 |

| 12 | うつ病性障害 | 4,635.9 | 1.8 | 601 |

| 13 | 肝硬変 | 4,279.8 | 1.7 | 555 |

| 14 | 気管、気管支、肺がん | 4,137.8 | 1.6 | 537 |

| 15 | 腎臓病 | 4,057.1 | 1.6 | 526 |

| 16 | HIV / AIDS | 4,014.7 | 1.6 | 521 |

| 17 | その他の難聴 | 3,947.7 | 1.6 | 512 |

| 18 | 墜死 | 3,821.6 | 1.5 | 496 |

| 19 | マラリア | 3,339.8 | 1.3 | 433 |

| 20 | 裸眼の屈折異常 | 3,198.1 | 1.3 | 415 |

歴史については「精神保健の歴史」を参照

世界保健機関︵WHO︶によって、障害調整生命年︵DALY︶のうち、精神障害が占める割合が大きいことが報告されて以来、その対策の必要性が大きく唱えられることとなった[8]。精神的な健康は、著しい苦痛や生活の機能において障害をもたらす段階になった場合、精神障害であると診断されうる[9]。

各国は、精神科医や臨床心理士、精神保健福祉士といった精神保健専門家︵Mental health professional︶を育成する仕組みを持ち、その対策にあたっている。例えば、世界保健機関による人権に根差したメンタルヘルスケアに関する﹃精神保健ケア法10原則﹄[10]は、言い換えると精神保健福祉法は、基本的人権として精神的な健康の増進があり、そのための治療も人権に配慮すべきであるという原則をまとめたものである。

世界保健機関による﹃疾病及び関連保健問題の国際統計分類﹄第10版︵IDC-10︶で定義される範囲は、﹁精神および行動の障害 (Mental and behavioural disorders)﹂であり、そこには、アルツハイマー型認知症のような認知機能の問題から、依存症のような薬物関連障害、または統合失調症やうつ病のような精神障害が含まれている[11]。

つまり、精神的な健康を保ち、薬物依存症のような不適切で有害なストレス対処法に陥らず、また認知能力を維持していくことは、福祉領域における関心ごとである。ただし、精神的な変調はストレスだけを原因とするものでもないため、甲状腺機能低下症の症状や、統合失調症やパーソナリティ障害、また医薬品による物質関連障害であったりもする[12]。うつ病とストレスばかりが強調され、適切な診断の鑑別がなされないまま、うつ病であるかどうかも定かではない状態に対して多剤大量処方がなされるという問題もまた、福祉領域の別の関心ごとである。

予防の面では、適切なストレスの対処法を覚え、精神面において肯定的な状態を増進していくことや、認知機能を維持していくことは、よりよい十全な健康の実現に欠かせないことである。そしてまた、理性と感情が葛藤し合うというようなまだ精神的に不健康な状態よりは、人間的成熟を目指していくということが必要であろう[13]。また、自然とのふれあいも重要であり[14]、幸福と健康の双方においては社会的なつながりも重要である[15]。

OECD各国の人口10万あたり精神保健従事者数。

青は精神科医、赤は臨床心理士、橙は精神保健福祉士。

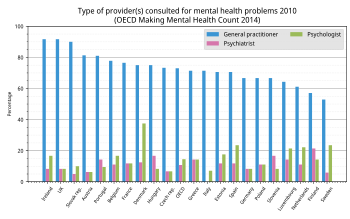

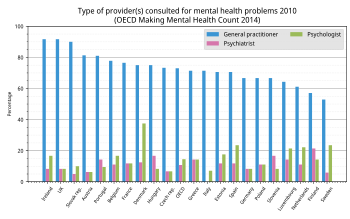

OECD各国のメンタルヘルス問題時の受診先調査[25]。

青は総合診療医、赤は精神科医、緑は臨床心理士。

WHOの2004年の報告では、障害調整生命年︵DALY︶の上位20障害のうち、大うつ病性障害、アルコール障害、精神病︵双極性障害、統合失調症など︶の精神障害が多くを占めていた[8]。

またOECD諸国においては、人口の約50%は人生のある時において精神障害を経験するとされる[26]。市民の平均15%[26]、労働年齢人口の20%ほど[27]が精神保健問題にて医療機関を受診している。重症の障害を持つ人々は失業リスクが6-7倍となり、平均寿命は一般より20年も短い[26]。

しかし治療が必要とされる人の60%が、治療を受けられていないとOECDは推定している[26]。メンタルヘルスの未治療率について、WHOは2004年に、統合失調症は32.2%、うつ病は56.3%、気分変調症は56.0%、双極性障害は50.2%、パニック障害は55.9%、全般性不安障害は57.5%、強迫性障害は57.03%、アルコール乱用・依存は78.1%だと推定している[28]。

世界の約3分の1︵36%︶の国々において、公式承認された精神障害の管理・治療マニュアルが、主なプライマリヘルスケア診療所にて存在しているとWHOは報告している[29]。OECDはプライマリケアに携わる総合診療医に対して、市民の精神保健について中心的な役割を果たすことを期待している[30]。

定義[編集]

世界保健機関[編集]

Mental health is not just the absence of mental disorder. It is defined as a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community. 精神的健康とは、単に精神障害でないということではない。それは、一人一人が彼または彼女自らの可能性を実現し、人生における普通のストレスに対処でき、生産的にまた実り多く働くことができ、彼または彼女の共同体に貢献することができるという、十全にある状態であると定義されている。 — 世界保健機関、2007、引用文の出所[3] 世界保健機関の世界保健機関憲章前文には﹁健康﹂の定義があり、単に病気ではないだけでないとし、達成しうる水準の健康を共有することは基本的人権であるとしている[16]。そして平和と安全の基礎となるとしている[16]。 さらに憲章には目的として、第1条において人々が可能な限りの健康水準に達することを宣言しており、第2条の機関の任務における各種の宣言において、その(m)項では、精神的健康︵Mental health︶、特に人間関係の調和に焦点を当てることを宣言している[16]。 最良の健康に到達することが基本的人権であるため、世界保健機関の目的とするところでもあるということである。それは精神的な健康においてもである。 さらには、1999年には憲章の健康の定義に、身体、精神だけでなく、スピリチュアルにも健康であることを追加するという提案がなされ賛成過多であったが[17]、現行の憲章で適切に機能しているということで採用には至らなかった[18]。日本の精神保健福祉法[編集]

日本の精神保健及び精神障害者福祉に関する法律においては、第1条に目的が示され、国民の﹁精神保健﹂を向上させるという狙いのために、精神障害者における医療と保護、生活とまた社会復帰と自立の促進に必要な支援、また発生を予防し、国民の﹁精神的健康﹂を保持し、増進すると宣言されている。さらに第3条でそれは義務だとしている。行動的健康[編集]

Behavioral Healthcareについて、米国の雇用主団体であるNational Business Group on Health[19]は、精神障害、行動障害、あるいは嗜癖障害に関する医療サービスだと説明しており[20]、アメリカ連邦政府の﹁アメリカのメンタル・ヘルス・ケアの変革について。連邦行動指針﹂[21]においても、behavioral health を含んで mental health が語られている。対象は、ICD-10と同じような範囲である。その他[編集]

アメリカ国立精神衛生研究所は、﹁The National Institute of Mental Health﹂である。心の健康を表現する方法には、様々な言い方がある[22]。 日本では精神科という言葉を使わずに﹁メンタルヘルス科﹂という名称を用いる病院もある。日本において、﹁メンタルヘルス﹂とあえてカタカナで呼ぶのは﹁精神病﹂﹁精神障害﹂﹁精神が病んでしまって﹂という言葉につきまとう偏見、スティグマ︵烙印︶を避けるための、ソフトな表現にしたいという意見もある[23]。精神保健政策[編集]

世界保健機関︵WHO︶のファクトシートでは以下が挙げられている。 精神保健10の事実︵10 FACTS ON MENTAL HEALTH︶ (一)世界の児童・青年のうち、約20%が精神障害・問題を抱えている。 (二)精神障害・物質乱用は、世界の障害者の多数を占める。 (三)世界では、毎年約80万人が自殺で亡くなる。 (四)戦争と災害は、精神保健と精神的健康に大きな影響を与える。 (五)精神障害は、他の傷病︵意図的な外傷、意図しない外傷など︶と同じ、大きな疾病上昇リスクファクターである。 (六)患者や患者家族へのスティグマ・差別は、人々を精神障害の治療から遠ざける。 (七)多くの国々では、精神障害・社会的行動障害をもつ人々への人権侵害が繰り返し行われている。 (八)精神保健従事者の人的資源は、世界的に大きな偏りがある。 (九)精神保健サービスの普及を妨げる障壁は主に5つあり、公衆衛生政策の欠如と財源不足、現状の精神保健サービス団体、プライマリケアとの連携欠如、従事者人材の不足、公衆精神衛生におけるリーダーシップ欠如である。 (十)サービス向上のために割かれる財源は、現状では相対的に控えめである。 — 世界保健機関、2014年[24]

「精神障害#疫学」も参照

受診までの期間[編集]

Duration of untreated psychosis︵精神病未治療期間、DUP︶とは、精神障害発症︵first episode psychosis、FEP︶から初回受診までの期間のこと[31]。DUPが長いほど障害が長期化すると言われている[31][32]。英国保健省の精神保健政策ガイドライン[33]ならびに世界的コンセンサスでは[31]DUPを3か月未満とすることを目標としているが、多くの国々では非常にDUPが長い現状であり、ある研究では平均10年以上と言われている[34]。とりわけ若年者については、多くのOECD諸国では未治療率が最も高く、かつ治療されるまでの待ち時間も最長であった[34]。

たとえば、豪州においてはDUPは平均8.7週間[35]、米国においては1-3年[31]、日本の統合失調症患者においては平均34.6ヶ月︵中央値10.5ヶ月︶[36]と報告されている。

DUP短縮のため、メンタルケアへの受診につなげる取り組みは重要であり、特にプライマリケアに注力すべきとOECDは勧告している[37]。たとえば英国ではIAPTプログラムの実施により、2010-2012年間に一般的な精神障害を持つ110万人に加療を行い、回復率は45%であったと報告されている[37]。同様に、豪州ではEEPIC︵The Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre︶[38]、ノルウェーではTIPS[39]、デンマークではOPUS[40]といった早期介入の取り組みが進められている。

反スティグマ・キャンペーン[編集]

「精神障害#スティグマ」も参照

OECDは精神障害の偏見に対してへの反スティグマ・キャンペーンを提案している[41]。その対象は、市民全体でもあれば、労働者、医療提供者、教育者、若年者、賃貸大家なども対象に挙げている[42]。OECDにおいて、とくに英国、カナダ[43]、豪州は国家レベルにて市民を対象とした反スティグマ・キャンペーンを実施している[42]。またフィンランド、ノルウェー、スウェーデンでは学校授業として若年者に直接反スティグマ教育を実施している[42]。

たとえばOECDは英国スコットランドにおける﹁See Me﹂キャンペーンを取り上げており、﹁4人に1人が精神障害を経験する[44]﹂として、映画、テレビ広告、ポスター、ウェブサイト[1]で展開され、またマザーウェルFCは試合期間中に﹁Let's Stop the stigma of mental illness﹂Tシャツを着用していた[42][45]。SeeMeサイトでは、約3人に2人︵61%︶の人が身近に精神障害の経験者がいることを知っているし、最も多い障害はうつ病、パニック発作、重度ストレス、不安障害であり、長期的な精神障害について3分の2以上の人が回復するというスコットランドのデータが示されている[44]。これにより精神障害者は危険だと思う人の割合は2002年の32%から2009年には19%に減少した[44]。

またOECDは、欧州委員会が3年計画で実施したThe Anti Stigma Programme: European Network (ASPEN)を取り上げており、これはEU28ヶのうつ病を対象としている[42]。それにおいてASPENは、非ヨーロッパ諸国︵特に米国と豪州︶ではうつ病への反スティグマキャンペーンが欧州よりも頻繁に行われており、これは製薬会社の資金が理由であると述べている[42]。ASPENはキャンペーンの質的評価の欠如を示唆している[42]。

分野[編集]

職場[編集]

詳細は「産業精神保健」を参照

児童・青年[編集]

多くの精神障害は児童青年期に発症する[46]。WHOによれば世界の児童・青年のうち、約20%が精神障害・問題を抱えている[24]。精神障害発症の中央値はOECD諸国では14歳前後であるが[46]、しかし治療受給は発症後から平均で12年後となっており[46]、成人患者の過半数以上らは児童青年期の発症がそのまま継続したものであった[34]。不安障害やパーソナリティ障害の発症は中央値が11歳であった[47]。

| オーストリー | スイス | 英国 | オランダ | ベルギー | スウェーデン | 豪州 | デンマーク | 米国 | ノルウェー | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 中程度 | 13% | 12% | 14% | 15% | 17% | 17.2% | 19% | 18% | 22% | 20% |

| 深刻 | 2% | 5% | 3% | 5% | 5% | 5% | 4% | 7% | 6% | 8% |

| 計 | 15% | 17% | 18% | 20% | 21% | 22% | 22% | 25% | 28% | 29% |

| 平均 | 25%値 | 75%値 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 不安障害 | 11歳 | 6歳 | 21歳 |

| 気分障害 | 30歳 | 18歳 | 43歳 |

| 衝動制御障害 | 11歳 | 7歳 | 15歳 |

| 物質乱用 | 20歳 | 18歳 | 27歳 |

| 精神障害すべて | 14歳 | 7歳 | 24歳 |

| 男 | 女 | 総数 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD | 6.5% | 1.0% | 3.8% |

| 反抗挑戦性障害 | 2.1% | 1.6% | 1.9% |

| 物質乱用 | 9.3% | 4.2% | 6.8% |

| 行為障害 | 2.6% | 1.1% | 1.9% |

| 気分障害/不安障害 | 7.9% | 16.5% | 12.1% |

| 精神障害すべて | 24.4% | 22.5% | 23.4% |

| 5–10歳 | 11–15歳 | |

|---|---|---|

| 行為障害 | 2.8% | 3.5% |

| 多動性障害 | 0.6% | 0.3% |

| 感情障害 | 2.5% | 4.3% |

| 行為+感情 | 0.6% | 1.1% |

| 行為+多動 | 0.6% | 0.8% |

| 多動+感情 | 0.1 % | <0.1% |

| 行為+多動+感情 | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| 総数 | 7.3% | 10.1% |

精神不調を訴える子どもには、学校が支援を提供すべきであり、とりわけ家族が子どもをサポートできない場合にその役割は重要である[34]。精神不調問題が子どもにとってスティグマにならないよう、すみやかに生徒と教師に対してメンタルヘルス教育を施すようOECDは勧告しており、その例として豪州のKidsMatter、MindMattersプログラムを挙げている[34]。

老年期[編集]

「老年精神医学」も参照

認知症は70歳以上人口において2番目に多数を占める障害疾患であり、95歳以上では約半数が罹患している[52]。全世界で440万人が認知症を抱えて生活を送っており、その経済的コストは全世界で毎年0.5兆米ドル以上とされる[52]。

個人における精神の充足[編集]

個人において、精神的な健康を維持し増幅させるためには、大部分には、身体における生活習慣病の予防策と同じであり、食事や運動、またストレス管理によって、心身ともに対処することが可能である[53]。

「精神科の治療#ケアの基本」も参照

ジャンクフードのような認知機能を低下させる食事よりも、ビタミンB群やオメガ3脂肪酸に富んだ食事は、認知機能を高め維持し、気分を良く保つ影響を与える[54]。運動には、軽症から中等度のうつ病の治療として推奨されうるほどの効果があり[55]、その予防にも効果がある[56]。また運動は脳卒中後の認知機能の回復も高める[57]。

呼吸法によるリラクセーションは、怒りの管理や心理療法でも用いられる[58]。睡眠や[59]、笑うことも自律神経のバランスを整えるとも言われる[60]。

否定的な影響を感じる相手とは適切な距離を保つという方法もある︵個人の境界線︶。また心理学は、アサーションと呼ばれる自己主張の方法も重視しており、自己の理想願望が過剰であることによってそれが達成できずストレスを感じていることを是正したり、あるいはそうして相手に対する期待を無理のないお願いに是正した上で、適切な方法で主張するということである。そうしてそれが不可能である場合には、肯定的な影響を感じる人々との接触を増やすことである。重要な人々とのコミュニケーションは、ストレス解消ともなる。

対して、不適切なストレスの発散方法は、怒りを爆発させることによって問題を引き起こしたり、不適切にアルコールなどの薬物を摂取すること︵セルフメディケーション︶によって、精神的健康また身体的健康にわたって悪影響をおよぼすことがある。

自然とのふれあいは、認知機能や幸福感を高める[14]。

考え方のクセと呼ばれる認知的な方法も可能である。﹁せねばならない﹂という思い込みや、﹁黒か白か﹂といった二分思考は認知行動療法によって修正可能な思考のクセの焦点の一部である。否定的な思考を過剰に繰り返す状態を是正することでいくらか気分が改善されることもある[61][62]。

しかしながら、精神的な変調は、更年期障害や甲状腺機能低下症の症状であったり、アルコールなどの薬物、気管支喘息に対する医薬品といったことも原因となりえ、過度に個人的な努力やストレスを強調すれば、判断を誤りうる。また現在病気喧伝といった問題があり、正常に近い健康状態に対して、過剰に多剤大量処方が行われることがあり、これが原因となって逆に体調がすぐれないこともある。

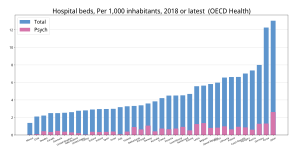

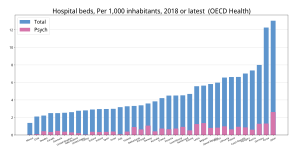

OECD諸国の人口あたりベット数︵機能別︶

精神保健医療は混迷の中にある。

世界の精神医療は、ここ数十年間の間に脱施設化︵Deinstitutionalisation、患者を施設からコミュニティケアへ︶を目標政策としてきている[6]。OECDは、多くの国々︵米国、英国、豪州、フランス、イタリア、ノルウェー、スウェーデン︶ではほぼ脱施設化を達成したが、しかし日本と韓国のような国ではいまだ施設入院が主流であると報告している[6]。

各国の精神保健[編集]

| 期間 | 日本 | フィンランド | ドイツ | オランダ | アイルランド | デンマーク | 韓国 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1年以下 | 35% | 82% | 100% | 28% | 58% | 90.0% | 67% |

| 1-5年 | 29% | 11% | 0% | 38% | 18% | 9.7% | 25% |

| 5年以上 | 36% | 7% | 0% | 34% | 25% | 0.3% | 8% |

WHOの指針[編集]

2012年の第66回WHO総会では﹁Mental health action plan 2013 - 2020﹂が可決され、各国は人権に配慮した根拠に基づくユニバーサルヘルスケアを推進し、また2020年までの達成目標として以下を挙げている[4]。

精神保健アクションプラン︵Mental health action plan︶2013 - 2020

(一)世界の80%の国々が、国際・地域の人権規約に即して、精神保健の政策/計画を策定または更新する︵2020年までに︶。

(一)世界の50%の国々が、国際・地域の人権規約に即して、精神保健のための法律を制定または更新する︵2020年までに︶。

(二)重度の精神障害に対するサービスの適用範囲を20%増加する︵2020年までに︶。

(三)世界の80%の国々が、少なくとも2つの、機能している、国の多部門による精神保健の促進と予防プログラムを持つ︵2020年までに︶。

(一)各国の自殺死亡率を10%減少させる︵2020年までに︶。

(四)世界の80%の国々が、国の保健医療・社会情報システムにより、中核となる精神保健指標を少なくとも1セット以上、2年毎に定期的に収集・報告する︵2020年までに︶。

— 世界保健機関 2013

EU諸国の精神保健[編集]

OECDによれば、EU諸国の市民のうち6人に1人が精神保健問題を抱えており、およそ8400万人と推定されている︵2016年︶[63]。疾患別では、不安障害︵市民の5.4%︶、うつ病︵4.5%︶、薬物・アルコール問題︵2.4%︶、双極性障害︵1.0%︶、統合失調症︵0.3%︶と推定される[63]。推定有病率の上位国はフィンランド、オランダ、アイルランドであり︵18.5%以上︶、下位国はルーマニア、ブルガリア、ポーランドであった︵15%以下︶[63]。この差は、精神疾患に対する問題意識が高く、スティグマが少なく、保健サービスへのアクセスが容易であることが挙げられる[63]。 精神障害を抱えたままでは、学業や職業において成功する可能性は乏しく、失業となる可能性が高く、また身体的な健康問題も引き起こされるとOECDは指摘する[63]。そのコストはGDPの6%︵2400億ユーロ︶以上と推定されており、医療費に1700億ユーロ︵GDPの1.2%︶、社会保障支出に1,700億ユーロ︵1.2%︶、労働市場における間接コストに2400億ユーロ︵1.6%︶とされる[63]。EUでは精神衛生上の問題および自殺により、8.4万人以上が死亡した︵2015年︶[63]。EU諸国は自殺防止の取り組みを進めており、その結果、EU28か国の半数では自殺率が20%以上減少した[63]。産業精神保健の取り組みもなされ、オーストリア、ベルギー、フィンランド、フランス、ノルウェー、オランダでは、労働法において心理的労働安全衛生リスク対策を行っている[63]。イギリスの精神保健[編集]

| 一般的な精神障害 | 16% |

| うつ病エピソード | 3% |

| 恐怖症 | 2% |

| 全般性不安障害 | 4% |

| PTSD スクリーニング | 3% |

| ADHDスクリーニング | 1% |

| 精神病 | 1% |

| 過去の自殺試行 | 1% |

| 薬物依存 | 3% |

| アルコール依存 | 6% |

| アルコール問題 | 24% |

| 精神障害すべて | 23% |

イギリスの精神障害による経済的損失は700億ポンド︵GDPの4.5%︶と推定されており[65]、主な離職原因でありESA受給者の40.9%を占めている[66]。英国保健省の統計によれば、イングランドでは成人の6人に1人が人生のある時点で精神保健問題を経験し、また5-16歳の児童青年では10人に1人が精神障害を抱え、多くは罹患したまま成人となる[67][68]。初回罹患は平均14歳で、4分の3は20歳中盤までに罹患し、100人に約1人は深刻な障害である[68]。65歳以上人口では35%が罹患している[64]。また成人の約半数は人生のある時点でうつ病を最低1回は経験する[68]。

| 大うつ病性障害 | 気分変調症 | 全般性不安障害 | パニック障害 | 特定の恐怖症 | 社交不安障害 | 強迫性障害 | PTSD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-10% | 2.5-5% | 5.7% | 1.4% | 12.5% | 12% | 1.6% | 6.8% |

医療制度の評価は高く、政策決定、公的機関、民間機関それぞれの意思決定において問題意識が共有され、精神障害へのスティグマ削減と施政向上に共に取り組んでおり[69]、軽中程度の患者に対しては根拠に基づく心理療法が施され、OECDは他国が参考にすべき先進的な精神保健制度を持っていると評している[70]。

イギリスは世界で最も﹁脱施設化﹂に取り組んでいる国の一つであり、人口10万あたりの病床数は54床で︵2011年︶これはOECD平均の68床よりも少ない[70]。うつ病および恐怖症の90%はプライマリケアの場において診断・治療されている[67]。診療報酬制度でもイギリスは先進的であると評され、精神医療には成果に基づく支払制度︵ペイ・フォー・パフォーマンス︶が導入され、これにより長期入院から通院型加療へのシフトに成功した[70]。医療制度のアウトカム指標であるHealth of the Nation Outcome Scales︵HoNOS︶も評価が高く、豪州とニュージーランドにも導入された[70]。

イタリアの精神保健[編集]

イタリアは脱施設化の先駆者であり︵バザリア法︶、人口あたり精神病床数は明らかにOECD諸国にて低水準を達成している[71]。イタリアは20年かけて病床数削減を達成し、コミュニティベースに移行した[71]。自殺率も2000-2010年の間に -13.4%も削減できた︵OECD平均は -7%︶[71]。イタリアは予定外の再入院率︵双極性障害と統合失調症︶も削減できており、これは外来診療とコミュニティケアがよく機能している指標だとOECDは評している[71]。オーストラリアの精神保健[編集]

| 年齢 | 16-24 | 25-34 | 35-44 | 45-54 | 55-64 | 65-74 | 75+ | 総数 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 男性 | 22.7% | 22.7% | 20.7% | 18.5% | 10.8% | 7.7% | 4.8% | 17.6% |

| 女性 | 30.0% | 26.8% | 25.8% | 24.0% | 16.3% | 9.5% | 6.8% | 22.3% |

オーストラリア保健省の国家統計によれば、16-85歳の市民およそ2人に1人が︵45.5%︶、人生のどこかの時点で不安、情動、物質乱用の障害を経験する[72]。インタビューにおいて過去12ヶ月の間、7人に1人︵14.4%︶が不安障害を、16人に1人︵6.2%︶が情動障害を、20人に1人︵5.1%︶が物質乱用を経験している[72]。

政府は制度改革を進めており、病床数は1960年と比べて約9割の削減を成し遂げ、OECD平均より明らかに脱施設化を達成している[73]。保健支出はコミュニティケアにシフトしており、多種多様なサービスが提供されている[73]。しかしOECDはサービスごとの配分バランスや、地域格差などを挙げて、それら住民のニーズにより対応するよう勧告している[73]。

またプライマリケアにおいては、軽~中等症の障害には心理療法へのアクセスを改善する取り組み︵Access to Allied Psychological Services、ATAPSプログラム︶を進めており、計6回の短期間セッションが提供される[74]。またウェブベース認知行動療法プログラム︵MoodGYM︶が開発され、これはフィンランド、オランダ、ノルウェー、中国にも普及した[73]。OECDはオーストラリアにおける職場の精神保健による経済的損失は年間590億豪ドルに上るとし、これらの取り組みの継続を評価している[73]。

カナダの精神保健[編集]

| 年齢 | 9-12 | 13-19 | 20-29 | 30-39 | 40-49 | 50-59 | 60-69 | 70-79 | 80-89 | 90+ | 総数 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 男性 | 15.1% | 29.1% | 28.7% | 26.3% | 19.5% | 12.8% | 10.6% | 17.8% | 28.3% | 33.8% | 18.7% |

| 女性 | 15.6% | 25.9% | 28.1% | 25.0% | 20.6% | 17.5% | 17.6% | 25.9% | 36.7% | 42.1% | 20.9% |

| 男 | 女 | 総数 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 不安障害/気分障害 | 7.9% | 15.4% | 11.7% |

| 統合失調症 | 0.61% | 0.61% | 0.61% |

| 物質乱用 | 8.6% | 3.2% | 5.9% |

| 認知症 | 1.7% | 2.6% | 2.2% |

| 精神障害すべて | 18.7% | 20.9% | 19.8% |

カナダにおいては、20-29歳人口では28%以上、40歳までには2人に1人が、90歳までには男性の65%以上と女性の70%が、人生のある時点で精神障害を経験する[49]。カナダの精神障害は670万人以上であり、これは糖尿病タイプ2患者︵220万人︶、心臓病患者︵140万人︶と比較される[49]。

カナダ保健省配下のカナダ精神保健委員会によれば、毎年5人に1人の市民が精神障害になり、労働人口の約21.4%が精神障害を経験し、精神保健問題の経済的コストは最低でも500億加ドル︵GDPの2.8%︶と推定され、労働生産性への影響は64億加ドル以上であるという[49]。

また児童青年に対して早期予防を図ることで経済的コストを削減できるという強いエビデンスがあり、カナダ精神保健委員会は、もし新規の精神障害者を10%減らせたならば、少なくとも年間40億加ドルの経済的コストを削減できると推定している[49]。

フィンランドの精神保健[編集]

General Health Questionnaireに基づく30歳以上人口に対しての調査によれば、フィンランドの精神障害の罹患率は17.4%で、うち男性14.8%、女性19.5%であり、50-64歳が最も高かった[75]。障害別では不安神経症︵6.2%︶、神経症性うつ病︵4.6%︶が上位であった[75]。 医療制度については、OECDは脱施設化の成果を上げており、若年者の精神障害リスクと遠隔地医療に焦点を当てた注目すべき制度であると評している[76]。フィンランドでは2000-2010年の間、プライマリケアにおける精神保健支出を倍増しているが、一方で施設入院費用は削減を達成した[76]。また若年者に重点的な施策がなされ、学校にて精神保健教育プログラムが整備されている[76]。また遠隔医療が整備され、ビデオ会議のような形でプライマリケア医を支援する仕組みがある[76]。しかしフィンランドは高い自殺率が長年の課題であり、自殺率削減は進んでいるものの依然に高水準である[76]。フランスの精神保健[編集]

| 年齢 | 18-30 | 30-40 | 40-50 | 50-65 | 65+ | 総数 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 気分障害 | 男 | 12.9% | 12.3% | 12.2% | 10.3% | 7.9% | 11.2% |

| 女 | 18.0% | 15.9% | 16.5% | 15.4% | 14.2% | 15.9% | |

| 不安障害 | 男 | 22.1% | 19.1% | 19.0% | 15.8% | 10.0% | 17.4% |

| 女 | 29.9% | 26.8% | 27.8% | 26.5% | 17.7% | 25.4% | |

| アルコール問題 | 男 | 9.7% | 9.0% | 7.6% | 6.7% | 2.6% | 7.2% |

| 女 | 2.6% | 1.9% | 1.4% | 1.1% | 0.5% | 1.5% | |

| 薬物問題 | 男 | 11.8% | 4.2% | 1.9% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 3.9% |

| 女 | 4.2% | 1.1% | 0.8% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 1.2% | |

フランスでの精神科患者数︵2002年調査︶はおよそ30 - 50万人と言われる。そのうちの20 - 25万人が統合失調症であるとされる。フランス厚生省配下の衛生監視研究所(InVS)によるサンプリング調査での有病割合は、気分障害では男性11%、女性16%、不安障害では男性17%、女性25%、アルコール問題では男性7%、女性1.5%、薬物問題では男性4%、女性1%であった[77]。これらすべてにおいて、18-29歳における有病割合が最も高かった[77]。

精神科医は人口10万人あたり22.3人である︵2011年︶[78]。この数はスイス、アイスランドに次いで多く[78]、フランス国内の全専門医の13%にあたるとされる。なお精神科看護師は58000人で不足している。

スウェーデンの精神保健[編集]

スウェーデンでは、市民の24%が、精神保健問題で医療機関を受診している︵OECD平均は14%︶[47]。とくに若者市民の20%以上が精神障害を持っていたため︵2000年末︶、子どもの精神保健に重点が置れている[47]。政府は精神保健対策の必要性を認識しており、フィンランドやノルウェーと同様に、学校教育において精神保健への反スティグマ・プログラムを設定している[47]。ノルウェーの精神保健[編集]

ノルウェーの精神保健制度は良好であり、人口全体に対して幅広く適切なケアを提供できているとOECDは評している[79]。軽〜中等症の障害については他のOECD諸国と同様、総合診療医(GP)が中心となって治療を行い、GPは認知行動療法(CBT)の研修を受けており保険適応される[79]。深刻な障害についてはGPの紹介状をもとに専門医が治療する[79]。またウェブベースのCBTプログラム︵MoodGYM︶が無料で提供されたり、イギリスに類似した心理療法アクセス改善(IAPT)プログラムの試験実施が行われている[79]。 人口あたりの病床数はOECD平均を上回るが、過去10年間で病床削減を成し遂げており入院から外来へのシフトが進んでいる[80]。しかし再入院率が高いため連携が今後の課題であるとOECDは評している[80]。またノルウェー統計庁によれば15-24歳市民の16.5%が深刻な心理的ストレスを抱えているとされ、適切な治療なしには学力低下・就労困難をまねくため、児童青年層に注意を払うべきであるとOECDは勧告している[80]。日本の精神保健[編集]

詳細は「日本の精神保健」を参照

OECDは﹁日本の精神医療には、緊急の行動を要する課題がある。高い自殺率、精神科病床数の多さ及び平均入院期間の長さによって、日本の精神医療制度は良くない理由で注目を浴びている。現在入手可能なデータや情報が現状を評価するのに十分ではなく、全体像が不明瞭であり、これらの指標から、精神医療の質における主要な弱点がいくつか示唆されるが、日本の精神医療制度は徐々に変わりつつある。過去10年間のコミットメントと努力が、制度に前向きな変化を生み出しつつある。﹂[81][82]と報告している。

また精神障害の治療は、OECD諸国においては主に総合診療医が担っているが、日本のプライマリケア制度の整備は発展途上である[83]。OECDは、日本の地域医療を担う医療関係者は須らく精神保健の技能を身につけるべき[83]、具体的にはすべてのプライマリケア医の研修過程に軽中程度の精神障害に対する診断・治療技能を組み込むよう勧告している[81][82]。厚労省は﹁G-Pネット﹂としてプライマリケア医と精神科医の連携を進める政策を取っている[84][85]。

シンガポールの精神保健[編集]

| 年齢 | 18-29 | 30-39 | 40-49 | 50-59 | 60-69 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 男性 | 14.1% | 13.9% | 14.6% | 5.3% | 6.8% |

| 女性 | 22.6% | 18.4% | 10.9% | 7.8% | 6.3% |

| 総計 | 18.4% | 16.2% | 12.7% | 6.5% | 6.6% |

シンガポール保健省の2010年国家保健調査によれば、女性︵14.1%︶のほうが男性︵11.5%︶よりも精神保健状態は良くない︵poor︶とされた[86]。

国家機関であるシンガポールメンタルヘルス機構が実施した、2010年のThe Singapore Mental Health Study (SMHS) によれば、大うつ病性障害、アルコール乱用、強迫性障害が3大障害であった[87][88]。人生のある時点で、市民の49.2%がうつ病を、3.6%が全般性不安障害または強迫性障害を、0.5-3.1%がアルコール依存を経験する[87]。

精神障害を経験した人は、22.1%は精神科医に、21.6%はカウンセラーに、18%は総合診療医に、12%は伝統医療を受診していた[87]。平均発症年齢は29歳で、発症から受診するまでの期間はアルコール乱用は14年、双極性障害と強迫性障害は9年、全般性不安障害とうつ病は5年であった[87]。

途上国における精神保健[編集]

WHOは中所得国において、精神保健サービスを必要とする人のうち、5人に4人が適切なケアを受給できていないと推定している[53]。2008年にWHOは低中所得国を対象とした改善計画 Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) を開始し、精神、神経、薬物乱用を対象としたクリニカルパスおよび診療ガイドラインを公開している[53]。メンタルヘルスを取り巻く社会状況[編集]

「産業精神保健#課題」も参照

社会的コスト[編集]

精神障害は大きな社会的経済コストをもたらし、また個人の主要な貧困の要因である[89]。

| 英国 | イスラエル | ドイツ | ギリシャ | オーストリー | 欧州平均 | フランス | アイルランド | ベルギー | デンマーク | スペイン | ポルトガル | スウェーデン | イタリア |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.5% | 4.3% | 3.8% | 3.6% | 3.6% | 3.6% | 3.5% | 3.4% | 3.4% | 3.4% | 3.4% | 3.4% | 3.4% | 3.4 |

| スベロニア | オランダ | ハンガリー | フィンランド | スイス | ポルトガル | ノルウェー | エストニア | チェコ | 米国 | スロバキア | ルクセンブルク | 豪州 | |

| 3.3% | 3.3% | 3.2% | 3.2% | 3.2% | 3.1% | 2.9% | 2.7% | 2.7% | 2.5% | 2.5% | 2.2% | 2.2% |

精神に問題を持つ人の大部分は就業しており、深刻な障害を持つ人の50%ほどは就業している[91]。貧困と精神障害には関連性があり[92]、就業率について健常者と比べて、軽~中等症の患者では10~15%、重度の患者では25~30%も低かった[91]。またうつ病と貧困には高い関連性があった[92]。

| 低世帯所得の比率 | 精神保健状態別 | 市民全体 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 重症の障害 | 中等症 | 障害なし | ||

| 米国 | 43.3% | 23.9% | 16.9% | 20.0% |

| 英国 | 42.4% | 33.7% | 23.6% | 25.7% |

| 豪州 | 37.3% | 19.6% | 12.6% | 15.0% |

| デンマーク | 30.8% | 25.5% | 15.0% | 17.4% |

| オーストリー | 27.0% | 23.0% | 20.1% | 20.9% |

| スウェーデン | 27.0% | 22.0% | 16.0% | 18.0% |

| ベルギー | 19.2% | 16.4% | 10.1% | 11.5% |

| スイス | 18.8% | 15.9% | 11.0% | 14.6% |

| ノルウェー | 18.4% | 13.6% | 7.8% | 9.5% |

| 直接的な 医療コスト |

直接的な 非医療コスト |

間接的コスト | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 気分障害 | €781 | €464 | €2,161 |

| 精神病 | €5,805 | €0 | €12,991 |

| 不安障害 | €670 | €2 | €405 |

| 睡眠障害 | €441 | €0 | €348 |

| 児童青年の障害 | €439 | €3156 | €0 |

| パーソナリティ障害 | €773 | €625 | €4,929 |

| 摂食障害 | €400 | €48 | €111 |

障害給付の増加[編集]

| 給付項目 | 平均 | 下位国 | 上位国 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 障害給付 | 46.4% | 31.9% | 65.7% | ||

| 傷病給付 | 53.9% | 30.2% | 73.2% | ||

| 失業給付 | 29.2% | 23.6% | 35.1% | ||

| 公的扶助 | 45.2% | 33.1% | 66.3% | ||

| (豪州、オーストリー、ベルギー、デンマーク、オランダ、 ノルウェー、スウェーデン、スイス、英国、米国) | |||||

アメリカでの障害給付は1987年の125万人から、2007年の400万人に増加した。イギリスにおける精神と行動の障害による障害給付は、2000年の74.5万人から2013年の100万人以上へと38%増加した。同様の増加傾向は他の先進国でも見られ、それは金融危機よりも先に増加している[94]。

| デンマーク | 英国 | オランダ | スウェーデン | スイス |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40.9% | 39.6% | 39.0% | 37.4% | 37.1% |

| 豪州 | ベルギー | オーストリー | 米国 | ノルウェー |

| 35.4% | 33.3% | 31.1% | 28.3% | 27.9% |

さらにWHOは、2030年には障害調整生命年(DALY)の1位の障害は、うつ病となると推測している[95]。

病気喧伝[編集]

「病気喧伝」も参照

精神障害の増加の一端には、製薬会社による病気喧伝がもたらしてきたものがある。日本におけるうつ病、注意欠陥多動性障害、社会不安障害、双極性障害の診断の乱発もそうである[96]。2012年にも、アメリカ国立精神衛生研究所︵NIMH︶所長であるトーマス・インセルは、医薬品の売上とは反対に、うつ病、統合失調症、双極性障害といった一般的な障害を含む重篤な精神障害を有する人々の障害の罹患率や死亡率が減少していないことを報告している[97]。

2013年には﹃精神障害の診断と統計マニュアル﹄第4版︵DSM-IV︶の編集委員長であるアレン・フランセスは、精神障害の数が急増しているというよりは、粗雑な診断が増え、安易に薬が処方されているため、流行の診断名による診断と過剰診断を減らすことが必要だとしている[98]。

製薬会社が新しい薬を販売することによって、病気喧伝がなされ、発売以前の2倍にも診断が下されるようになるという現象が各国にて起きている[99]。軽症のうつ病を説明する﹁心の風邪﹂というキャッチコピーは、2000年ごろから日本で特に抗うつ薬パキシルの市場を開拓するために、グラクソ・スミスクラインによる強力なマーケティングによって用いられた[100]。薬の売り上げは2000年からの8年で10倍となり、協力したアメリカ人医師は、節操などなく下衆な娼婦だった、と明かしている[101]。後に、軽症のうつ病に対する抗うつ薬の効果に疑問が呈され、安易な薬物療法は避けるよう推奨された[102]。

日本における新型うつの流行と議論[編集]

﹁心の風邪﹂の宣伝文句により人々にとって精神科が身近になる中、樽味伸は2004年にうつ病のディスチミア親和型を提唱した[103]。うつ病の患者の中に、仕事熱心でなく、他罰的で、抗うつ薬が効かない患者が増えていることに気づいたからである[103]。後に、新型うつ病のステレオタイプ、仕事では元気がないがプライベートは元気という言説につながるが、これは樽味の意図したことではない[104]。これは古くは、﹁退却神経症﹂あるいは﹁逃避型抑うつ﹂とか、近年では樽味のディスチミア親和型の他に、阿部による﹁未熟型うつ病﹂、松浪による﹁現代型うつ病﹂などによって異なる病理が描かれていたが、共通した特徴としては、典型的なうつ病よりも抗うつ薬が効きにくく、軽症かつ難治ということである[105]。一方、﹁非定型うつ病﹂とは﹃精神障害の診断と統計マニュアル﹄︵DSM︶においては、特定の症状を持つうつ病を指しているが、この用語はマスコミなど一般に、典型的ではないうつ病を指して用いられている[105]。2012年には、テレビ番組のNHKスペシャルにて、﹁職場を襲う"新型うつ"﹂が特集され、同様の特徴が報道されている[106]。

日本うつ病学会は、2012年のうつ病の診療ガイドラインにおいて、﹁現代型︵新型︶うつ︹ママ︺﹂について、若年者の軽症の抑うつ状態の研究の一側面を切り取ったマスコミ用語であり、精神医学的な深い考察も、治療のための根拠も欠いているとしている[107]。日本うつ病学会は、ウェブサイト上にて、その概念も学術的に検討されたものではないとしている[105]。

啓蒙活動[編集]

- 10月 世界メンタルヘルスデー (WHO協賛)

- メンタルヘルス週間(オーストラリア)

- 5月メンタルヘルス月間(アメリカ)

脚注[編集]

出典[編集]

(一)^ OECD 2012, p. 98.

(二)^ The WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium (2004). “Prevalence, Severity, and Unmet Need for Treatment of Mental Disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys”. JAMA 291 (21): 2581. doi:10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. ISSN 0098-7484.

(三)^ ab世界保健機関 (2007年9月3日). “What is mental health?”. World Health Organization. 2014年6月24日閲覧。

(四)^ ab世界保健機関 2013.

(五)^ 世界保健機関 2004, Introduction.

(六)^ abcdOECD 2014, pp. 15–16.

(七)^ Global health estimates: Leading causes of DALYs (Excel) (Report). 世界保健機関. 2020年12月. Download the data > GLOBAL AND BY REGION > DALY estimates, 2000–2019 > WHO regions. 2021年3月27日閲覧。

(八)^ ab世界保健機関 2004, p. 34.

(九)^ アメリカ精神医学会﹃DSM-IV-TR 精神疾患の診断・統計マニュアル︵新訂版︶﹄医学書院、2004年、249-250頁。ISBN 978-0890420256。

(十)^ 世界保健機関 (1996年). Mental Health Care Law : Ten Basic Principles / WHO/MNH/MND/96.9 (pdf) (Report). World Health Organization. 2014年6月20日閲覧。 、邦訳: 世界保健機関; 木村朋子 訳 (1996年). 精神保健ケアに関する法‥基本10原則 (pdf) (Report). 2014年6月20日閲覧。

(11)^ 世界保健機関 2013, Annex: Glossary of main terms.

(12)^ 春日武彦﹃病んだ家族、散乱した室内 : 援助者にとっての不全感と困惑について﹄医学書院、2001年9月、113-119頁。ISBN 9784260331548。

(13)^ 小林司﹃﹁生きがい﹂とは何か―自己実現へのみち﹄日本放送出版協会︿NHKブックス﹀、1989年、134,141頁。ISBN 4-14-001579-9。

(14)^ abBerman, Marc G.; Jonides, John; Kaplan, Stephen (December 2008). “The Cognitive Benefits of Interacting With Nature” (pdf). Psychological Science 19 (12): 1207–1212. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02225.x. PMID 19121124.

(15)^ Fowler, J. H; Christakis, N. A (2008). “Dynamic spread of happiness in a large social network: longitudinal analysis over 20 years in the Framingham Heart Study”. BMJ 337 (dec04 2): a2338–a2338. doi:10.1136/bmj.a2338. PMC 2600606. PMID 19056788.

(16)^ abc世界保健機関憲章 (PDF) ︵外務省︶

(17)^ “WHO憲章における﹁健康﹂の定義の改正案について”. 厚生省 (1999年3月19日). 2014年6月25日閲覧。

(18)^ “WHO憲章における﹁健康﹂の定義の改正案のその後について︵第52回WHO総会の結果︶”. 厚生省 (1999年10月26日). 2014年6月25日閲覧。

(19)^ National Business Group on Health

(20)^ 矢倉尚典; 川端勇樹﹁米国におけるメンタルヘルス分野のヘルスサポートの取り組み﹂︵pdf︶﹃損保ジャパン総研クォータリー﹄第49巻、4頁、2007年12月31日。

(21)^ Transforming Mental Health Care in America. The Federal Action Agenda: First Steps

(22)^ About.com (Updated March 02, 2010). “What Is Mental Health?”. 2012年7月7日閲覧。

(23)^ 島 悟﹃メンタルヘルス入門﹄日経文庫、2007年4月、32頁。

(24)^ ab10 FACTS ON MENTAL HEALTH - Mental health: a state of well-being (Report). WHO. 2014年8月.

(25)^ OECD 2014, p. 63.

(26)^ abcdOECD 2014, pp. 15–18.

(27)^ OECD 2014, Executive Summary.

(28)^ Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, Saraceno B (2004). “The treatment gap in mental health care”. Bull. World Health Organ. (世界保健機関) 82 (11): 858–66. PMC 2623050. PMID 15640922.

(29)^ 世界保健機関 2011, p. 35.

(30)^ OECD 2014, pp. 16–18.

(31)^ abcdThomas Insel, M.D. (2013年2月8日). Reducing the Duration of Untreated Psychosis in the United States (Report). アメリカ国立精神衛生研究所.

(32)^ Marshall M; Lewis S; Lockwood A; Drake R; Jones P; Croudace T (2005). “Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: a systematic review”. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62 (9): 975–983. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.975. PMID 16143729 2009年2月14日閲覧。.

(33)^ Mental health policy implementation guide: Dual diagnosis good practice guide (Report). 英国保健省. 2001年.

(34)^ abcdeOECD 2015, p. 17.

(35)^ Schimmelmann, Benno G.; Huber, Christian G.; Lambert, Martin; Cotton, Sue; McGorry, Patrick D.; Conus, Philippe (2008). “Impact of duration of untreated psychosis on pre-treatment, baseline, and outcome characteristics in an epidemiological first-episode psychosis cohort”. Journal of Psychiatric Research 42 (12): 982–990. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.12.001. ISSN 00223956.

(36)^ Lihong, Qin; Shimodera, Shinji; Fujita, Hirokazu; Morokuma, Ippei; Nishida, Atsushi; Kamimura, Naoto; Mizuno, Masafumi; Furukawa, Toshi A. et al. (2012). “Duration of untreated psychosis in a rural/suburban region of Japan”. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 6 (3): 239–246. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7893.2011.00325.x. ISSN 17517885.

(37)^ abOECD 2015, pp. 17–18.

(38)^ The Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre (EPPIC)

(39)^ TIPS

(40)^ Petersen L; Nordentoft M; Jeppesen P; Ohlenschaeger J; Thorup A; Christensen TØ; Krarup G; Dahlstrøm J et al. (2005). “Improving 1-year outcome in first-episode psychosis: OPUS trial”. British Journal of Psychiatry 187 (Supplement 48): s98-s103. doi:10.1192/bjp.187.48.s98. PMID 16055817.

(41)^ OECD 2014, pp. 231–232.

(42)^ abcdefgOECD 2014, pp. 231–235.

(43)^ Beyond the Label (Report). Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. 2005年. ISBN 978-0-88868-506-3。

(44)^ abc英国ジャーナリスト連合; スコットランド政府. Responcible reporting on mental health, mental illness & death by suicide (PDF) (Report).

(45)^ ﹃Motherwell FC Makes New Signing to Tackle Stigma of Mental Ill Health﹄︵プレスリリース︶Elament、2010年6月17日。

(46)^ abcdOECD 2015, p. 40.

(47)^ abcdOECD 2014, Country press releases - Sweden.

(48)^ OECD 2012, p. 178.

(49)^ abcdefgMaking the Case for Investing in Mental Health in Canada (Report). Mental Health Commission of Canada. 2013年2月8日.

(50)^ abThe Life and Economic Impact of Major Mental Illnesses in Canada (Report). Mental Health Commission of Canada. 2013年2月9日.

(51)^ Paul McCrone; Sujith Dhanasiri; Anita Patel; Martin Knapp; Simon Lawton-Smith (2008年5月28日). Paying the Price - The cost of mental health care in England to 2026 (Report). King's Fund. Chapt.10. ISBN 9781857175714。

(52)^ abAddressing Dementia - The OECD Response (Report). OECD. 2015年3月13日. Chapt.1. doi:10.1787/9789264231726-en。

(53)^ abc* mhGAP Intervention Guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings (2 ed.), 世界保健機関, (2016), ISBN 9789241549790

(54)^ Gómez-Pinilla, Fernando (July 2008). “Brain foods: the effects of nutrients on brain function”. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 9 (7): 568–578. doi:10.1038/nrn2421. PMC 2805706. PMID 18568016.

(55)^ Josefsson, T.; Lindwall, M.; Archer, T. (April 2014). “Physical exercise intervention in depressive disorders: Meta-analysis and systematic review”. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 24 (2): 259–272. doi:10.1111/sms.12050. PMID 23362828.

(56)^ Sui, Xuemei; Laditka, James N.; Church, Timothy S.; Hardin, James W.; Chase, Nancy; Davis, Keith; Blair, Steven N. (February 2009). “Prospective study of cardiorespiratory fitness and depressive symptoms in women and men”. Journal of Psychiatric Research 43 (5): 546–552. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.08.002. PMC 2683669. PMID 18845305.

(57)^ Sui, Xuemei; Laditka, James N.; Church, Timothy S.; Hardin, James W.; Chase, Nancy; Davis, Keith; Blair, Steven N. (November 2009). “Prospective study of cardiorespiratory fitness and depressive symptoms in women and men”. Journal of Psychiatric Research 43 (5): 546–552. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.08.002. PMC 3024242. PMID 19541916.

(58)^ 湯川進太郎﹃怒りの心理学 : 怒りとうまくつきあうための理論と方法﹄有斐閣、2008年、第7章 pp113-125。ISBN 978-4-641-17341-5。

(59)^ CAREERzine (2010年). “効率的に仕事をするなら﹁起きてる場合じゃない﹂睡り博士に聞く!ビジネスパーソンに最適な眠りの方法”. 2012年7月8日閲覧。

(60)^ gooヘルスケア McKee (2008年). “病気のもとは笑いとばす”. 2012年7月7日閲覧。

(61)^ 慶應義塾大学認知行動療法研究会﹃うつ病の認知療法・認知行動療法︵患者さんのための資料︶﹄︵PDF︶疾病・障害対策研究分野 こころの健康科学研究、2010年1月。

(62)^ 大野裕ら﹃平成23(2011)年度 精神療法の実施方法と有効性に関する研究 総括﹄2012年3月。 データベースから文献番号 200400769A

(63)^ abcdefghi Health at a Glance‥Europe 2018, OECD, (2018), Chapt.1, doi:10.1787/health_glance_eur-2018-en.

(64)^ abThe mental health strategy for England - Annex B: Evidence base from (No Health Without Mental Health strategy: analysis of the impact on equality) (Report). 英国保健省. 2011年2月2日. Table.4.

(65)^ OECD 2014, pp. 13.

(66)^ OECD 2014, p. 41.

(67)^ abcCG123 - Common mental health disorders: Identification and pathways to care (Report). 英国国立医療技術評価機構. 2011年4月. Introduction.

(68)^ abcThe mental health strategy for England - No Health Without Mental Health: a cross-government mental health outcomes strategy for people of all ages (Report). 英国保健省. 2011年2月2日.

(69)^ Mental Health and Work: United Kingdom, Mental Health and Work (Report). OECD. 2014年. doi:10.1787/9789264204997-en。

(70)^ abcdOECD 2014, Country press releases - UK.

(71)^ abcdOECD 2014, Country press releases - Italy.

(72)^ abcThe mental health of Australians 2 (Report). オーストラリア保健省. 2007年. Chapt.2 An overview of mental disorders in Australia.

(73)^ abcdeOECD 2014, Country press releases - Australia.

(74)^ OECD 2014, p. 86.

(75)^ abLehtinen, V.; Joukamaa, M.; Lahtela, K.; Raitasalo, R.; Jyrkinen, E.; Maatela, J.; Aromaa, A. (1990). “Prevalence of mental disorders among adults in Finland: basic results from the Mini Finland Health Survey”. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 81 (5): 418–425. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb05474.x. ISSN 0001-690X.

(76)^ abcdeOECD 2014, Country press releases - Finland.

(77)^ abcPrévalence des troubles de santé mentale et conséquences sur l’activité professionnelle en France dans l’enquête “Santé mentale en population générale : images et réalités” (PDF) (Report). Institut de veille sanitaire. 2007年8月.

(78)^ abOECD 2013, Chapt.3.4.

(79)^ abcdOECD Reviews of Health Care Quality: Norway 2014: Raising Standards (Report). OECD. 2014年5月21日. Chapt.4. doi:10.1787/9789264208469-en。

(80)^ abcOECD 2014, Country press releases - Norway.

(81)^ abOECD Series on Health Care Quality Reviews - Japan (Report). OECD. 2014年11月. Assessment and Recommendations.

(82)^ ab﹁OECD医療の質レビュー / 日本 / スタンダードの引き上げ / 評価と提言﹂2014年11月5日 (PDF)

(83)^ abOECD 2014, Country press releases - Japan.

(84)^ “G-Pネット”. 一般医・精神科医ネットワーク研究会事務局. 2015年1月20日閲覧。

(85)^ ﹃平成19年版 自殺対策白書﹄︵レポート︶内閣府、Chapt.2.2。

(86)^ abNational Health Survey 2010 (Report). シンガポール保健省. 2011年11月. Chapt.16.

(87)^ abcd"Latest study sheds light on the state of mental health in Singapore" (PDF) (Press release). Institute of Mental Health (Singapore). 18 November 2011.

(88)^ Subramaniam, Mythily; Vaingankar, Janhavi; Heng, Derrick; Kwok, Kian Woon; Lim, Yee Wei; Yap, Mabel; Chong, Siow Ann (2012). “The Singapore Mental Health Study: an overview of the methodology”. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 21 (2): 149–157. doi:10.1002/mpr.1351. ISSN 10498931.

(89)^ OECD 2015, Chapt.1.

(90)^ abOECD 2015, p. 29.

(91)^ abOECD 2015, p. 30.

(92)^ abOECD 2014, pp. 57–58.

(93)^ abOECD 2015, p. 33.

(94)^ ﹃Council for Evidence-based Psychiatry launches today with data showing dramatic rise in mental health disability﹄︵プレスリリース︶Council for Evidence-based Psychiatry、2014年4月30日。2014年6月4日閲覧。

(95)^ 世界保健機関 2004, p. 51.

(96)^ 井原裕﹁双極性障害と疾患喧伝︵diseasemongering︶﹂︵pdf︶﹃精神神経学雑誌﹄第113巻第12号、2011年、1218-1225頁。

(97)^ Insel, T. R. (October 2012). “Next-Generation Treatments for Mental Disorders”. Science Translational Medicine 4 (155): 155ps19–155ps19. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3004873. PMID 23052292.

(98)^ アレン・フランセス﹃精神疾患診断のエッセンス―DSM-5の上手な使い方﹄金剛出版、2014年3月、7-8頁。ISBN 978-4772413527。、Essentials of Psychiatric Diagnosis, Revised Edition: Responding to the Challenge of DSM-5®, The Guilford Press, 2013.

(99)^ 冨高辰一郎﹃なぜうつ病の人が増えたのか﹄幻冬舎ルネッサンス、2010年、ISBN 978-4779060267

(100)^ Kathryn Schulz (2004年8月22日). “Did Antidepressants Depress Japan?”. The New York Times 2013年1月10日閲覧。

(101)^ アンドルー・ワイル﹃ワイル博士のうつが消えるこころのレッスン﹄上野圭一(翻訳)、角川書店、2012年9月、53-54頁。ISBN 978-4041101582。、Spontaneous Happiness, 2011

(102)^ 日本うつ病学会; 気分障害のガイドライン作成委員会﹃日本うつ病学会治療ガイドライン II.大うつ病性障害2012 Ver.1﹄︵PDF︶︵レポート︶︵2012 Ver.1︶日本うつ病学会、気分障害のガイドライン作成委員会、2012年7月26日、20-23頁。2013年1月1日閲覧。

(103)^ ab佐藤陽 (2011年12月8日). “一丁上がり 増殖する病” 2014年8月17日閲覧。

(104)^ 黒木俊秀﹁うつ病医療のポピュラリゼーションと日本的うつ病論のゆくえ﹂﹃精神医学の羅針盤﹄篠原出版新社、2014年7月、54-58頁。ISBN 978-4884123765。

(105)^ abc﹃Q4.新型うつ病が増えていると聞きます。新型うつ病とはどのようなものでしょうか?﹄︵pdf︶︵レポート︶日本うつ病学会。2014年6月24日閲覧。

(106)^ 職場を襲う "新型うつ"、NHKスペシャル、2012年4月29日放送

(107)^ 日本うつ病学会﹃日本うつ病学会治療ガイドライン﹄︵PDF︶︵レポート︶2012年7月26日、3-4頁。

参考文献[編集]

国際機関 ●Mental Health Atlas 2011 (Report). 世界保健機関. 2011年. ●Mental health action plan 2013 - 2020 (Report). 世界保健機関. 2013年. ISBN 9789241506021。 ●The global burden of disease: 2004 update (Report). 世界保健機関. ISBN 9241563710。 ●Prevention of mental disorders Effective interventions and policy options (Report). 世界保健機関. 2004年. ISBN 924159215X。 ●Making Mental Health Count - The Social and Economic Costs of Neglecting Mental Health Care (Report). OECD. 2014年7月. doi:10.1787/9789264208445-en。 ●﹃OECD によると、多くの国で精神医療は資源不足﹄︵プレスリリース︶OECD、2014年。 ●Sick on the Job? - Myths and Realities about Mental Health and Work (Report). OECD. 2012年. doi:10.1787/9789264124523-en。 ●Fit Mind, Fit Job - From Evidence to Practice in Mental Health and Work (Report). OECD. 2015年3月. doi:10.1787/9789264228283-en。関連項目[編集]

●精神保健の歴史 ●精神医学 / 精神障害 / 精神病院 ●精神保健法 / Category:精神保健法 ●産業精神保健 ●性格と病気 ●m:Mental health resources - ウィキメディア・プロジェクト全体に関する議論等を行うメタウィキメディアにて、Wikipediaを運営しているウィキメディア財団の信頼と安全チームがメンタルヘルス対応相談窓口のリストを管理し情報を提供している。 ●ドゥームスクロール(ドゥームサーフィン) - 人間は悲劇的な情報を集中して集めてしまう傾向があり、これによってメンタルヘルスに影響を及ぼすことがわかっている。外部リンク[編集]

- Mental Health and Substance Use(英語) - WHO

- Mental Health(英語) - OECD

- Mental health(英語) - 英国NHS

- こころの情報サイト - 国立精神・神経医療研究センター(個人向け)

- こころもメンテしよう ~若者を支えるメンタルヘルスサイト~ - 厚生労働省(個人・学生向け)

- 『メンタルヘルス』 - コトバンク

- メンタルヘルスとは?意味や職場、対策方法、日本の状況について紹介! - yururi