トレント号事件

トレント号事件︵トレントごうじけん、英: Trent Affairまたはメイソン・スライデル事件、英: Mason and Slidell Affair︶は、アメリカ合衆国の南北戦争中に外交問題に発展した事件である。1861年11月8日、アメリカ海軍︵北軍︶のチャールズ・ウィルクス海軍中佐が指揮するUSSサンジャシントがイギリスの郵便船RMSトレントを拘束し、南軍の外交官、ジェイムズ・マレー・メイソンとジョン・スライデルの2人を戦時禁制として連行した。この2人はアメリカ連合国が独立国としてヨーロッパで外交認知されるために、イギリスとフランスに向かわせた使節だった。

アメリカ合衆国の最初の反応はイギリスに対する反発であり、戦争突入を思わせるものだったが、エイブラハム・リンカーン大統領とその外交顧問は開戦の危険性を望まなかった。アメリカ連合国は、この事件でイギリスとアメリカ合衆国の関係を壊すことになるのを期待し、さらにはそれがイギリスによるアメリカ連合国認知に繋がることも望んだ。アメリカ連合国はその独立がイギリスとアメリカ合衆国の間に起こる戦争に依存する可能性を認識していた。イギリスでは、この事件がイギリスの中立でいる権利の侵害であり、国の名誉に対する侮辱だと見なした大衆が怒りを表した。イギリスの政府は謝罪と捕虜の解放を要求し、一方ではカナダと大西洋における軍事力増強に動いた。

緊張感が高まり、開戦の噂が流れてから数週間後に、リンカーン政権が使節を釈放し、ウィルクス大佐の行動を否認したことで、危機が回避された。公式の謝罪は無かった。メイソンとスライデルはイギリスへの旅を再開したが、アメリカ連合国が諸外国から認知されるという目的は果たせなかった。

ウィリアム・スワード︵1801年-1872年︶、1860年から1 865年に撮影

パーマストン︵1784年-1865年︶

外交に関する北軍の方向性はまるで反対だった。すなわち南部︵アメリカ連合国︶をイギリスが認知するのを妨げることだった。1850年代を通じて、イギリスとアメリカの関係は改善が進んでいた。オレゴン境界紛争、テキサス州に関わるイギリスの関与、およびカナダ国境の問題は全て1840年代に解決されていた。アメリカ合衆国国務長官ウィリアム・スワードが南北戦争の間の外交政策では主要な立案者であり、アメリカ独立戦争以来機能してきた外交の原則を維持するつもりだった。すなわち他国の事情にアメリカ合衆国が干渉しないこと、およびアメリカ合衆国と西半球諸国の事情への外国からの干渉を阻止することだった[2]。

イギリスの首相パーマストンは、中立政策を主導していた。国内の関心はヨーロッパに向けられており、特にフランスのナポレオン3世がヨーロッパに向けている野心と、プロイセンにおけるビスマルクの台頭を監視する必要があった。南北戦争の間のアメリカに対するイギリスの反応は、過去のイギリスの政策と、戦略および経済における国益によって形作られていた。西半球では、アメリカ合衆国との関係が改善されているのと同様に、中央アメリカでの問題に関してもアメリカ合衆国と対立しないよう注意するようになっていた。イギリスは海軍強国として、敵国の海上封鎖を行う中立国の栄誉を以前から守ってきており、その考え方で南北戦争の初期より北軍の海上封鎖に対する﹁事実上の﹂支持を行い、南部の怒りを買うことになっていた[3]。

ワシントン駐在のロシア大使エドゥアルド・ド・ステッケルは、﹁ロンドンの内閣が北軍内部の不和を注意深く監視しており、北軍が表面を繕う難しさに耐えられなくなる結果を心待ちしている﹂と記していた。ド・ステッケルは、イギリスが早期にアメリカ連合国を認知することになると、母国に報告していた。ロシア駐在アメリカ大使のカシアス・マーセラス・クレイは﹁イングランドの感覚がどこを向いているか一目で分かる。彼等は我々の破滅を期待している!彼等は我々の力を嫉妬している。彼等にとっては南部でも北部でも構わない。彼等はどちらも憎いのだ。﹂と述べていた[4]。

南北戦争が始まったとき、ロンドン駐在アメリカ大使はチャールズ・フランシス・アダムズ・シニアだった。アダムズは、今回の戦争が厳密に国内の反乱であり、アメリカ連合国には国際法の下での権利を与えるものでないと、ワシントン政府が考えていることを明らかにしていた。イギリスが公式にアメリカ連合国を認知するような動きがあれば、アメリカ合衆国に対する非友好的な行為であると見なすはずだった。スワードがアダムズに与えた指示では、世界に領土が広がり、またスコットランドとアイルランドを含む母国があるイギリスは、﹃危険な前例を作る﹄ことに大きな注意を払うべきことをはっきりさせておくことだった[5]。

経験を積んだ外交官であるライアンズ卿がアメリカ駐在イギリス大使だった。ライアンズはスワードについて次のようにロンドンに警告していた。

彼︵スワード︶が危険な外務大臣になることを怖れざるを得ない。アメリカ合衆国とイギリスの関係に関する彼の見解では、政争の具になる良い材料である状態が常に続いていた...スワード氏が実際に我々との戦争に進もうと考えているとは思えないが、我々に対する力を示すことで、国内での人気を求める古いやり方を選ぶ可能性はある。[6]

ライアンズはスワードに対する不信にも拘わらず、1861年を通じて﹁冷静で図られた﹂外交を続け、﹁トレント号﹂危機でも平和的な解決に貢献した[7]。

ウィリアム・ローンズ・ヤンシー︵1814年-1863年︶

初代ラッセル伯ジョン・ラッセル︵1792年-1878年︶

﹁トレント号事件﹂は1861年11月下旬まで大きな危機として浮上しなかった。この事件に至る連鎖の最初のものは1861年2月のことであり、アメリカ連合国がウィリアム・ローンズ・ヤンシー、ピエール・ロストおよびアンブローズ・ダッドリー・マンの3人からなるヨーロッパ代表団を造った。アメリカ連合国国務長官ロバート・トゥームズが彼等に与えた指示は、南部政府の性格と目的を説明し、外交関係を開き、﹁友好、通商および航行に関する条約の交渉﹂にあたることだった。また州の権限と脱退できる権利に関する長い法的な主張も含まれていた。綿花と国の正当性に関して二重に攻撃されることが重荷だったので、南部の港の封鎖、私掠船、北部との貿易、奴隷制度および非公式封鎖など多くの重要問題に関する指示が抜けていた。非公式封鎖は南部人が綿花を出荷できないように仕組まれたものだった[8]。

イギリスの指導層、さらにはヨーロッパ大陸諸国の指導層は、アメリカ合衆国の分裂が避けられないと見るのが一般だった。北軍が﹁既成事実﹂に抵抗するのは不合理だと考えたが、北軍が対処しなければならない事実として、その抵抗を受け入れざるを得なかった。イギリスは戦争の帰趨が既に見えているものと考え、人道的な姿勢として戦争を終わらせるために採れる行動があると考えていた。ライアンズはラッセルから、戦争を終わらせる可能性があるならば、その職責と、その他の団体を用いるよう支持を受けていた[9]。

アメリカ連合国の外交使節は5月3日にイギリスの外務大臣ジョン・ラッセルと非公式に会見した。既にサムター要塞攻撃の知らせがロンドンに届いていたが、この会見では即座に戦争が始まるというようなことは議論されなかった。代表団はその新しい国の平和を維持する意図を強調し、北部が州の権限を破った対抗手段としてその脱退の正当性を説明した。彼等はその強烈な主張の締めくくりとしてヨーロッパに対する綿花の重要性を述べた。ラッセルがヤンシーに、アメリカ連合国によって奴隷貿易が再開されるかを尋ねたときのみ、奴隷制度が議論された︵ヤンシーは近い過去にそのようなことを提唱していた︶。ヤンシーはそれがアメリカ連合国の計画に入っていないと答えた。ラッセルは言質を与えず、この問題を閣僚会議で議論することを約束しただけだった[10]。

イギリスは一方で南北戦争に対する公式姿勢を決定しようとしていた。5月13日、ラッセルの進言に従ってヴィクトリア女王はアメリカ合衆国南部の交戦状態を認知することになる中立宣言を発した。これはアメリカ連合国の船舶が、外港でアメリカ合衆国の船舶が受けるのと同じ特権を受けられることを意味していた。アメリカ合衆国の船舶は中立国の港で燃料と物資を補給でき、修繕を受けられるが、軍需物資や武器は確保できないということだった。イギリスから遠く離れた植民地の港を使えるということは、世界中にある北軍の船舶を追撃できるということだった。フランス、スペイン、オランダおよびブラジルが追従した。交戦状態にあるということで、アメリカ連合国は物資を購入し、イギリスの会社と契約する機会が与えられ、北軍の船舶を探索して捕獲するために艦船を購入できることを意味していた。女王の宣言によって、イギリスは交戦するどちらの側にも軍事的に介入できず、戦争に使われる艦船の装備を行えず、海上封鎖を破れず、どちらの側の軍需物資、文書あるいは人員を運ぶこともできないことになっていた[11] 。

チャールズ・フランシス・アダムズ・シニア︵1807年-1886年 ︶

5月18日、アダムズはラッセルに会って中立宣言に抗議した。アダムズは﹁彼等︵アメリカ連合国︶が、あらゆる利点が利用できる状況下に、領土内にある港の一つでの行動︵アメリカ連合国が海洋における一つでも私掠行為を示す前にはそれらを海軍力と考えた︶を除けば、如何なる種類の戦争も維持できるという能力を示す前に﹂イギリスが交戦状態を認めていると論じた。この時点でのアメリカ合衆国の主要な関心は、交戦状態の認知が国の外交認知に向けた第一歩だということだった。ラッセルは外交認知をその時点で考えていないことを示したが、将来的にそれを否定できないものであり、もしイギリス政府の態度が変わるようであれば、アダムズに知らせることに合意した[12]。

一方ワシントンでは、イギリスによる中立宣言と、ラッセルがアメリカ連合国の代表団に会ったことに、スワードが動揺していた。スワードは5月21日付けのアダムズに宛てた手紙で、イギリスがアメリカ連合国代表団を受け入れたことに抗議し、アダムズにはイギリスが代表団と会合を続ける限り、イギリスには関わらないように命じた。イギリスが正式にアメリカ連合国を認知すれば、イギリスはアメリカ合衆国の敵になるところだった。リンカーン大統領はこの手紙を査閲し、表現を和らげ、アダムズにはラッセルに写しを渡さないこと、ただしアダムズが適切と考えた部分のみを伝えるように指示した。アダムズは修正された手紙に衝撃を受け、さらに全ヨーロッパに対して開戦の脅威を与えているようなものだと感じた。手紙を受け取った後の6月12日にラッセルと会見し、イギリスが平和を保っている国︵アメリカ合衆国︶に対抗する反乱者︵アメリカ連合国︶の代表としばしば会ってきたが、ラッセルはこれ以上代表団と会うつもりは無いことも告げられた[13]。

8月半ばにアメリカ連合国の外交認知に関する問題がさらに広がった。スワードは、イギリスがアメリカ連合国とパリ宣言に盛られた条件への合意を得るために密かに交渉していることに気づいた。1856年のパリ宣言では、私掠船を廃止し、﹁戦時禁制品﹂を除いて交戦国に運ばれる中立国の商品を保護し、海上封鎖はそれが有効である場合のみ認めることとしていた。アメリカ合衆国は当初この条約に調印できなかったが、北軍がアメリカ連合国の海上封鎖を宣言した後、スワードがイギリスとフランスに駐在する大使達に、アメリカ連合国が私掠船を使うことを制限する交渉を再開するよう命じた[14]。

初代ライアンズ子爵リチャード・ビッカートン・ペメル・ライアンズ

しかし5月18日、ラッセルはライアンズにアメリカ連合国からパリ宣言に対する同意を得るよう指示していた。ライアンズはこの任務をサウスカロライナ州チャールストン駐在の領事ロバート・バンチに任せた。バンチはサウスカロライナ州知事フランシス・ピケンズに会うよう指示された。バンチはその受けた指示通りに動かず、ピケンズは省略して、アメリカ連合国にパリ宣言への同意が﹁︵イギリスによる︶外交認知の第1ステップ﹂だと請け合った。バンチの軽挙は間もなく北軍の耳に届いた。イギリス生まれでチャールストンの商人ロバート・ミュアがニューヨーク市で逮捕された。ミュアはサウスカロライナの民兵隊大佐であり、バンチが発行したイギリスの外交官パスポートを所持し、イギリスの外交文書用郵袋を運んでいた。この郵袋にはバンチからイギリスに宛てた通信文の他に、アメリカ連合国寄りの小冊子、南部人からヨーロッパの文通相手に宛てた個人的書簡、および外交認知に関する会話を含めバンチがアメリカ連合国と行った交渉を詳述するアメリカ連合国の報告書が入っていた[15]。

この事態に直面したラッセルは、イギリス政府がアメリカ連合国から中立国商品︵私掠によるものではない︶に関する条約条項に対する合意を得ようとしていることを認めたが、それがアメリカ連合国に対する外交関係を拡大するための一歩であることは否定した。スワードは以前に交戦状態認知の時に示した反応とは異なり、この問題を追求しなかった。スワードはバンチの解任を要求したが、ラッセルは応じなかった[16]。

ナポレオン3世治下のフランスにおける外交政策の目標はイギリスとは違っていたが、概して南北戦争の対戦相手に関してはイギリスと似た立場を採り、イギリスを支持することも多かった。イギリスとフランスの協業は、アメリカ合衆国駐在フランス大使のメルシエとライアンズの間で始まった。例えば6月15日に中立宣言に関して二人でスワードに会おうとしたが、スワードは別々に会見することに固執した[17]。

1861年全期間と1862年秋までフランスの外務大臣はエドゥアルド・ソウヴネルだった。ソウヴネルは概して北軍寄りと考えられ、ナポレオン3世が当初アメリカ連合国の独立を外交認知しようと動いていたのを止めさせていた。ソウヴネルは6月にアメリカ連合国代表団の一人ピエール・ロストと非公式に会見し、外交認知を期待しないように告げていた[18]。

リンカーン大統領はフランス駐在大使にニュージャージー州のウィリアム・L・デイトンを任命した。デイトンには外交の経験が無く、フランス語を話せなかったが、パリ駐在総領事のジョン・ビゲローから大いに助けられた。アダムズがラッセルにアメリカ連合国の交戦国認知に関して抗議したとき、デイトンは同様な抗議をソウヴネルに行った。ナポレオン3世は南部との紛争を解決するためにアメリカ合衆国に﹁調停案﹂を提案しており、それに対してスワードは﹁調停案が受け入れられるものであれば、我々がそれに向けて進むか受け入れるべきかはそれ次第である﹂と認めるようデイトンに指示した[19]。

7月の第一次ブルランの戦いで南軍が勝利したという報せがヨーロッパに届いたとき、アメリカ連合国の独立は避けられないというイギリスの意見が強くなった。ヤンシーはこの戦場での成功という利点を生かすことを期待し、ラッセルとの会見を要請したが、これを拒否され、対話は文書によるべきことを告げられた。ヤンシーは8月14日に長い文書を提出し、アメリカ連合国が正式の認知を受けるべきとする理由を再度詳述し、ラッセルとの再会見を要請した。ラッセルが8月24日に﹁自称アメリカ連合国の﹂代表団に発した返事では、この戦争が独立のための戦争と言うよりも国内での問題だと認識するイギリスの立場を繰り返していた。イギリスの政策は﹁今後の戦局あるいはより平和的な交渉によって、交戦する二者のそれぞれの立場を決定づけるようなこと﹂があったときのみ変わることになる。会合の予定は立てられず、この時がイギリス政府とアメリカ連合国外交官との間に交わされた最後の対話となった。11月と12月にトレント号事件が起きると、アメリカ連合国はイギリスと直接対話する有効な方法を持たず、交渉の席から完全に外されたままとなった[20]。

8月までにヤンシーは病気になって憤懣も募り、辞めようとしていた。やはり8月に、デイヴィス大統領は、一旦外交認知が済めば、アメリカ連合国大使として相応しい人物をイギリスとフランスに送る必要性があると決心していた。その選択はルイジアナ州のジョン・スライデルとバージニア州のジェイムズ・メイソンだった。二人とも南部中で広く尊敬を集めており、外交の経歴もあった。米墨戦争の終盤でジェームズ・ポーク大統領がスライデルを交渉担当に指名しており、またメイソンはアメリカ合衆国上院外交委員会で1847年から1860年まで委員長を務めていた[21]。

1861年7月、バージニア州のR・M・T・ハンターがアメリカ連合国国務長官になった。ハンターがメイソンとスライデルに与えた指示は、当初の7州から11州に拡大したアメリカ連合国の強い立場を強調し、メリーランド州、ミズーリ州およびケンタッキー州も最後はアメリカ連合国に加入する可能性が強いことを言うことだった。独立したアメリカ連合国はアメリカ合衆国の工業と海洋の野心を制限し、イギリス、フランスおよびアメリカ連合国の間に互恵的通商同盟を結ぶに至ることとされていた。アメリカ合衆国の領土的野望が制限されれば、西半球における力のバランスが回復されると考えられた。イギリスの支援で独立を勝ち取ろうとしているイタリアにアメリカ連合国を擬え、その支援を正当化するラッセル自身の文書を引き合いに出していた。差し当たり重要なこととして、北軍が行う海上封鎖の正当性に対して詳細な議論を行うこととされた。メイソンとスライデルは正式な文書と共に、彼等の立場を支持する多くの文書を携行した。

チャールズ・ウィルクス

これら外交官の出発意図は秘密ではなく[22]、アメリカ合衆国政府は日々彼等の動向について情報を受け取っていた。10月1日までに、スライデルとメイソンはチャールストンに居た。当初の計画では快速蒸気船のCSSナシュビルで封鎖線を突破し、直接イギリスに向かうつもりだった。しかし、チャールストン港に入る海峡は5隻の北軍艦船に護られ、ナシュビルの喫水が深かったので、海峡をすり抜けるのが難しかった。夜間の脱出も検討されたが、潮と夜間の強風のために決行できなかった。メキシコを陸路辿り、マタモロスから出港する案も検討されたが、これでは数か月遅延することになり、受け容れられなかった[23]。

代案として蒸気船のゴードンが提案された。ゴードンであれば喫水も浅いので裏ルートを抜けることができ、速力も12ノット以上が出せるので、北軍の追跡を振り切ることが可能だった。ゴードンアメリカ連合国政府が62,000ドルで買い上げるか、10,000ドルでチャーターする案が出された。アメリカ連合国財務省はこの金が出せなかったが、地元綿花ブローカーのジョージ・トレンホルムが帰りの航海で荷物室の半分を使用することと引き換えに10,000ドルを払った。ゴードンはセオドラと改名され、10月12日午前1時にチャールストン港を出港し、海上封鎖を行う北軍艦船もうまくすり抜けた。10月14日、バハマ諸島のナッソーに到着したが、カリブ海からイギリスに向かうイギリス船舶にとって主要な出発点であるデンマーク領西インド諸島のセントトマスに向かうイギリスの蒸気船に接続できなかった[24]。しかし、イギリスの郵便船がスペイン領キューバにいる可能性があることが分かり、南西のキューバに向かった。セオドラは10月15日にキューバの海岸沖に現れたが、その石炭室はほとんど空だった。接近してきたスペインの艦船がセオドラを出迎えた。スライデルとジョージ・ユースティス・ジュニアが乗船すると、イギリスの郵便船は確かにハバナ港のドックに居たが、出港したばかりであり、次の郵便船である外輪蒸気船RMSトレントが到着するのは3週間先であることを告げられた。セオドラは10月16日にカルデナスのドックに入り、メイソンとスライデルは下船した。この2人の外交官はカルデナスに留まり、その後に陸路ハバナに行って、次のイギリス郵便船に乗船することに決めた[25][26]。

一方、アメリカ合衆国政府にはメイソンとスライデルがナシュビルに乗って脱出したという噂が届いていた。北軍の情報部はメイソンとスライデルがセオドラでチャールストンを離れたことを即座に掴んでいなかった。海軍長官のギデオン・ウェルズはメイソンとスライデルがチャールストンを脱出したという噂に反応して、サミュエル・F・デュポン提督に快速艦船を2隻イギリスに向かわせ、ナシュビルを拘束するよう命じた。10月15日、ジョン・B・マーチャンドの指揮する北軍の側輪蒸気船USSジェイムズ・アジャーが、必要ならばイギリス海峡までナシュビルを追跡するという命令を持って、ヨーロッパに向かった。ジェイムズ・アジャーは11月初旬にイギリスに到着し、サウサンプトン港のドックに入った[25]。イギリス政府は、アメリカ合衆国が外交官を捕まえようとしていることに気づき、彼等がナシュビルに乗船していると思いこんでもいた。パーマストンは、ナシュビルが寄港すると予測される所の周辺3マイルをイギリス海軍の艦船に偵察させ、捕獲がイギリスの領海内で起こらないようにさせた。ジェイムズ・アジャーがナシュビルを追ってイギリス領海に入ったとしても、こうしておれば外交的な危機を避けることができると考えられた。ナシュビルが11月21日に到着すると、使節団が乗船していなかったので、イギリスは驚かされた[27]。

北軍のチャールズ・ウィルクス中佐が指揮する蒸気フリゲート艦USSサンジャシントが10月13日にセントトマスに到着していた。サンジャシントは1か月間近くアフリカ海岸沖を巡航した後、サウスカロライナ州ポートロイヤル攻撃の準備のために、アメリカ海軍に合流する命令を受けて西に向かっていた。しかしウィルクスはセントトマスで、アメリカ連合国のCSSサムターが7月にキューバのシエンフエーゴス近くでアメリカの商船3隻を捕獲したことを知った。サムターがそこに留まっている可能性は薄かったが、ウィルクスはそこに向かった。ウィルクスはシエンフエーゴスの新聞で、メイソンとスライデルが11月7日にイギリスの郵便船トレントでハバナを離れ、まずセントトマスに、続いてイギリスに向かう予定であることを知った。ウィルクスは﹁キューバと浅いグランドバハマ・バンクの間にある唯一水深の深い航路、バハマ海峡﹂をトレントが使う必要があることを認識した。ウィルクスは副指揮官であるD・M・フェアファックス少佐と法的に可能な選択肢を検討した後に、トレントの航行を妨害する作戦を立て、この問題に関する法律書も精査した。ウィルクスは、メイソンとスライデルがアメリカ合衆国の船舶によって捕獲する対象となりうる﹁戦時禁制﹂となるという考え方を採用した[28]。

この攻撃的な決断は指揮官としてのウィルクスの典型的なスタイルだった。ウィルクスは一方で﹁傑出した探検家、著作家および海軍士官﹂として認められていた[29]。しかし他方では﹁頑固で、熱心過ぎ、衝動的であり、時には命令に従わない士官であるという評判もあった[30]。財務官のジョージ・ハリントンはスワードに﹁彼︵ウィルクス︶は我々に問題をもたらす。彼は過剰なまでに自負心が強く、また判断には欠陥がある。大きな探査任務を指揮した時は、部下の士官のほとんど全員を軍法会議に掛けた。彼だけが正しく、他の者は全て間違いとなる﹂と警告していた[31]。

トレントは予定通り11月7日に出港し、メイソン、スライデルとその秘書官達、およびスライデルの妻子も乗船していた。ウィルクスがまさに予測したように、トレントはサンジャシントが待ち受けているバハマ海峡を通過した。11月8日の正午頃、サンジャシントの見張りがユニオンジャックを掲げたトレントを視認した。サンジャシントはトレントの船首越しに1発の砲弾を放ったが、トレントのジェイムズ・モワール船長はそれを無視した。サンジャシントの前側旋回砲が放った砲弾がトレントの前部に着弾した。この2発目に続いてトレントは停船した。フェアファックス少佐が後甲板に呼ばれ、ウィルクスから次のような文書の指示を受け取った。

あの船︵トレント︶に乗船し、蒸気船の書類、すなわちハバナの出港許可書と乗客乗員の名簿を求めること。

メイソン氏、スライデル氏、ユースティス氏およびマクファーランド氏が乗船している場合は、彼等を拘束し、この船に送りつけたうえで、あの船を戦利品として捕獲すること。 … 彼等は乗船しているに違いない。

彼等の所有するトランク、ケース、小包および袋の類は全て押収し、本船に送り届けること。捕虜の所有になる、あるいはかの蒸気船に乗り込む者の所有になる報告書の類も押収し、検査し、必要ならば保持すること。[32]

フェアファックスはカッターでトレントに漕ぎ寄せ乗船した。拳銃とカトラス︵短剣︶で武装した20人の部隊が2隻のカッターでトレントに横付けした[25][33]。フェアファックスは、ウィルクスが国際的な事件を起こそうとしており、その範囲を拡大しようとは望んでいないことを確信していたので、その武装護衛にはカッターの中に留まるよう命令した。フェアファックスは乗船すると、怒り心頭に発するモワール船長の所に連れて行かれ、そこで﹁メイソン氏とスライデル氏および彼等の秘書官を逮捕し、捕虜として近くのアメリカ合衆国の戦闘艦に連行する﹂命令を受けていると伝えた。乗員と乗客がフェアファックスを脅したので、トレントの船腹にある2隻のカッターの武装兵はこの脅しに反応して、船腹を上り、フェアファックスを護った。モワール船長はフェアファックスの要求した乗客名簿提出を断ったが、メイソンとスライデルが前に出てきて、自分達であることを確認した。モワール船長は船内の戦時禁制品捜索も拒否した。フェアファックスはこの問題を押すことはできなかった。それは船を戦利品として捕獲する必要があったからであり、それはほぼ間違いなく戦争行為だった。メイソンとスライデルは自発的にフェアファックスと同行することを正式に拒否したが、フェアファックスの部下がカッターに誘導したときには抵抗しなかった[25][34]。

ウィルクスは後に、トレントは﹁高度に重要な積み荷を運んでおり、アメリカ合衆国にとっては有害な指示を与えられていた﹂と考えたと主張することになった。フェアファックスが船内を捜索できなかったことに加えて、外交官が携行する手荷物に文書が見つからなかったことには別の理由があった。メイソンの娘が後の1906年に記したところに拠れば、トレントの乗客だったイギリス海軍のウィリアムズ中佐がアメリカ連合国の郵袋を確保しており、後にロンドンで代表団に戻されたということである。このことはヴィクトリア女王による中立宣言に対する明らかな違反だった[35]。

国際法では、﹁戦時禁制品﹂が船上で発見されたとき、その船は最も近い捕獲審判所に裁定を求めることとされている。これがウィルクスの当初の考えだったが、フェアファックスは、サンジャシントからトレントに乗員を移せばサンジャシントが危険なくらい手薄になり、またトレントの他の乗客や郵便の受取人にとっては甚だしく不都合になるので、ウィルクスに反対した。この場の責任者だったウィルクスはフェアファックスの主張に合意し、アメリカ連合国の2人の使節およびその秘書官達を除いて、トレントがセントトマスまで進むことを認めた[36]。

サンジャシントは11月15日にバージニア州ハンプトン・ローズに到着し、ウィルクスはワシントンに使節捕獲の報せを打電した。その後ボストンに行って、アメリカ連合国の捕虜を収容する施設であるウォーレン砦に捕虜を届けるよう命令された[37]。

フェアファックスはカッターでトレントに漕ぎ寄せ乗船した。拳銃とカトラス︵短剣︶で武装した20人の部隊が2隻のカッターでトレントに横付けした[25][33]。フェアファックスは、ウィルクスが国際的な事件を起こそうとしており、その範囲を拡大しようとは望んでいないことを確信していたので、その武装護衛にはカッターの中に留まるよう命令した。フェアファックスは乗船すると、怒り心頭に発するモワール船長の所に連れて行かれ、そこで﹁メイソン氏とスライデル氏および彼等の秘書官を逮捕し、捕虜として近くのアメリカ合衆国の戦闘艦に連行する﹂命令を受けていると伝えた。乗員と乗客がフェアファックスを脅したので、トレントの船腹にある2隻のカッターの武装兵はこの脅しに反応して、船腹を上り、フェアファックスを護った。モワール船長はフェアファックスの要求した乗客名簿提出を断ったが、メイソンとスライデルが前に出てきて、自分達であることを確認した。モワール船長は船内の戦時禁制品捜索も拒否した。フェアファックスはこの問題を押すことはできなかった。それは船を戦利品として捕獲する必要があったからであり、それはほぼ間違いなく戦争行為だった。メイソンとスライデルは自発的にフェアファックスと同行することを正式に拒否したが、フェアファックスの部下がカッターに誘導したときには抵抗しなかった[25][34]。

ウィルクスは後に、トレントは﹁高度に重要な積み荷を運んでおり、アメリカ合衆国にとっては有害な指示を与えられていた﹂と考えたと主張することになった。フェアファックスが船内を捜索できなかったことに加えて、外交官が携行する手荷物に文書が見つからなかったことには別の理由があった。メイソンの娘が後の1906年に記したところに拠れば、トレントの乗客だったイギリス海軍のウィリアムズ中佐がアメリカ連合国の郵袋を確保しており、後にロンドンで代表団に戻されたということである。このことはヴィクトリア女王による中立宣言に対する明らかな違反だった[35]。

国際法では、﹁戦時禁制品﹂が船上で発見されたとき、その船は最も近い捕獲審判所に裁定を求めることとされている。これがウィルクスの当初の考えだったが、フェアファックスは、サンジャシントからトレントに乗員を移せばサンジャシントが危険なくらい手薄になり、またトレントの他の乗客や郵便の受取人にとっては甚だしく不都合になるので、ウィルクスに反対した。この場の責任者だったウィルクスはフェアファックスの主張に合意し、アメリカ連合国の2人の使節およびその秘書官達を除いて、トレントがセントトマスまで進むことを認めた[36]。

サンジャシントは11月15日にバージニア州ハンプトン・ローズに到着し、ウィルクスはワシントンに使節捕獲の報せを打電した。その後ボストンに行って、アメリカ連合国の捕虜を収容する施設であるウォーレン砦に捕虜を届けるよう命令された[37]。

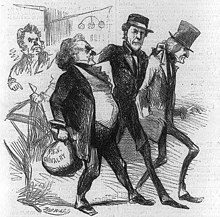

事件発生後、新聞紙に掲載されていた風刺漫画

北部人の大半は11月16日の新聞夕刊を飾ったトレント捕獲の記事で事件のことを知った。11月18日月曜日までに、新聞は﹁愛国心の迸りの大波に完全に飲まれている﹂ように見えた。メイソンとスライデルは、﹁檻に入った大使﹂であり、﹁ごろつき﹂﹁臆病者﹂﹁俗物﹂﹁冷淡で残虐でわがまま﹂と罵られた[38]。

全ての者がこの捕獲を法的に正当化することに熱心だった。ボストン駐在のイギリス領事は、2人に1人の市民が﹁小脇に法律書を抱えて歩き回り、サンジャシントがイギリスの郵便船を止めたその権利を証明しようとしている﹂と記していた。多くの新聞も同様にウィルクスの行動の合法性を論じ、多くの法律家はさらに進んでその正当性の承認を付け加えた[39]。ハーバードの法律学教授セオフィラス・パーソンズは﹁ウィルクスがメイソンとスライデルをトレントから連行する法的権利があることを確認し、それは我々の政府がチャールストンを封鎖する権利があるのと同じだ﹂と記した。著名な民主党員でフランクリン・ピアース政権で司法長官を務めたケイレブ・クッシングは、﹁私の判断では、ウィルクス船長の行動は、その事情に拘わらず、いずれもそして全ての自尊心のある国民がその主権と権力によってしなければならず、またしたであろうものである。﹂という考えに同意した。海事法の専門家と見なされるリチャード・ヘンリー・デイナ・ジュニアは、アメリカ連合国使節が﹁アメリカ合衆国に敵対的な任務に就いていた﹂故に身柄拘束は正当であり、﹁我々の自治法における反逆罪﹂で有罪であるとした。元イギリス駐在大使で国務長官も務めたエドワード・エヴァレットも、﹁身柄拘束は完全に合法であり、ウォーレン砦への収監も完全に合法になる﹂と論じている[40]。

11月26日にボストンのリビア・ハウスでウィルクスの栄誉を称える晩餐会が催された。マサチューセッツ州知事ジョン・A・アンドリューはウィルクスを﹁男らしく英雄的な成功﹂と誉め上げ、ウィルクスが﹁船首にイギリスのライオンを戴く船の舳先に砲弾を放った﹂とき、﹁アメリカ人の心を歓喜させた﹂と話した。マサチューセッツ州首席判事のジョージ・T・ビゲローはウィルクスのことを﹁北部の忠実な男達全ての常として、この6か月間ため息ばかりついてきたが、﹃私が責任を取る﹄と進んで自分に言い聞かせる人にとってはなおさらだったろう﹂と賞賛した[41]。12月2日、アメリカ合衆国議会はウィルクスに対して﹁反逆者ジェイムズ・M・メイソンとジョン・スライデルの逮捕と拘禁について、その勇敢で機敏で愛国的な行動に﹂感謝し、﹁彼の善行を議会が大いに楽しませてもらった証拠として、適当な標章と工夫を凝らした金メダル﹂を授与されることを提案する決議を全会一致で採択した[42]。

しかし事態を精査していくに連れて、人々は疑いを持ち始めた。海軍長官ギデオン・ウェルズは、ウィルクスの行動について海軍省の﹁断固たる承認﹂を記し、一方でトレントを捕獲審判所に曳航できなかったことは、﹁中立国の同様な義務違反への対応として今後の前例には決して認められないに違いない﹂と注意した時に多くの者が感じた曖昧さを回想していた[43]。11月24日、﹁ニューヨーク・タイムズ﹂はこの点で前例を見つけられなかったと報じた。サーロー・ウィードの﹁オルバニー・イブニング・ジャーナル﹂は、もしウィルクスが﹁保証されない判断をしたのならば、我々の政府はその手続きを適切に否定し、栄誉と公正に基づきイギリスの﹃あらゆる満足﹄を認めることになる、と示唆した[44]。メイソンとスライデルを捕まえたことは、昔の米英戦争に導いた原因であり、アメリカ合衆国がその誕生以来反対してきた強制徴用に大変類似しているとコメントする者が現れるまで長くは掛からなかった。戦時禁制として人間を捉えることは、多くの者に共感を持たせることはできなかった[45]。

ヘンリー・アダムズは強制徴用問題に関してその兄に次のように書いていた。

やれやれ、何てことだ?一体、我々の父達の偉大な原則を放棄し、いまいましいイギリスのやり方に戻ろうというのか。アダムズ家の誰もが抗議し抵抗してきたその原則に従おうというのか。貴方は狂っている。貴方達全員が狂っている。[46]

大衆もこの問題が法的に解決されるものというよりも、イギリスとの深刻な紛争を避ける必要性から解決されるべきことを認識し始めた。古参議員のジェームズ・ブキャナン、トマス・ユーイング、ルイス・カスおよびロバート・J・ウォーカー等は全て、捕虜を解放する必要性を訴えるようになった。12月の第3週までに、新聞の論調の大半はこれらの意見を反映して、アメリカ市民に捕虜解放に備えるように訴え始めていた[47]。ウィルクスが命令無しに動いて、実際にサンジャシントの甲板上で捕獲審判を行う誤りを犯したという意見が広まっていた[48]。

アメリカ合衆国は当初引き下がることを大変躊躇していた。スワードは、長い間のアメリカ合衆国による国際法の理解として、2人の使節を即座に釈放する機会を失っていた。11月末にスワードがアダムズに宛てた手紙では、ウィルクスが指示の下に動いたのではないが、イギリスから何らかの反応があるまで情報を伏せておくよう記していた。アメリカ連合国の認知は戦争に繋がる可能性が強いことも繰り返していた[49]。

リンカーンは当初捕虜捕獲に熱狂し、釈放には乗り気でなかったが、現実には次のように述べていた。

私は反逆者が白い象︵厄介者︶になることを怖れる。我々は中立国の権利に関するアメリカの原則に忠実であらねばならない。我々は、ウィルクス船長が行ったのとまさに同じ権利を主張して、イギリスと戦った。イギリスがこの行動に対して抗議し、捕虜の釈放を要求するならば、我々はそれに譲らねばならず、我々の原理の侵犯としてあの行動を謝罪し、かくして中立国に関連して平和を保つべくこの国を永遠に拘束する。またそれでこの国が60年間間違っていたことを認める。[50]

12月4日、リンカーンはカナダの財務大臣アレクサンダー・ゴールトと会見した。リンカーンはゴールトに、イギリスと事を構えることも、カナダに対して非友好的な考えを持つことも無いと伝えた。ゴールトが具体的にトレント号事件について尋ねると、リンカーンは﹁あー、あれはうまく解決されるでしょう﹂と答えた。ゴールトがこの会見の模様をライアンズに伝え、ライアンズはそれをラッセルに回送した。リンカーンが請け合ったにも拘わらず、ゴールトは﹁しかし私は、アメリカ政府の政策が世論に従順であるので、現在の状況では楽観はできないだろうし、期待すべきでもないという以前の考え方を変えることはできない﹂と記していた[51]。議会に対するリンカーンの年間教書は直接トレント号事件に触れなかったが、アメリカ合衆国は300万人の陸軍兵を動員できるという陸軍長官サイモン・キャメロンの推計に基づき、﹁国内での争乱に携わっていても、海外から自国を護ることができることを世界に示す﹂ことができると述べていた。

金融界もこの事件の行方に関わりがあった。財務長官サーモン・チェイスはヨーロッパにおけるアメリカの利益に影響するような事件を心配していた。ニューヨーク市の銀行が金の支払いを停止する意図があることに気づいており、クリスマスの日に行われた閣僚会議でスワードを支持する長たらしい議論を行うことになった。チェイスはその日記に、メイソンとスライデルを釈放することが﹁目標のようであり、私には辛いものである。しかし我々は事態を中途半端にしたまま遅れが許されず、大衆心理は穏やかでないままとなり、我々の商売には重大な支障を来し、反逆者に対する我々の行動は大きく妨げられるに違いない。﹂と記していた[52]。歴史家のウォーレンは、﹁トレント号事件では国内の銀行危機を引き起こさなかったが、大衆の信頼に寄りかかっていた戦時財政の場当たり的な仕組みを事実上崩壊させることに寄与した﹂と述べている[53]。

12月15日、イギリスの反応に関する最初の報せがアメリカ合衆国に届いた。イギリスは11月27日に事件のことを知ることになった。スワードが最初の新聞を持ってきたときに、リンカーンはオービル・ブラウニング上院議員と同席していた。その記事ではパーマストンが捕虜の釈放と謝罪を要求していた。ブローニングはイギリスによる戦争の恐れが﹁愚かなこと﹂と考えたが、﹁我々は死ぬまで戦うことになる﹂と述べた。その夜の外交レセプションで、スワードはウィリアム・H・ラッセルが﹁我々は全世界を炎で包むことになる﹂と言っているのを聞かされた[54]。議会のムードも変わっていた。12月16日と17日に問題に関して議論したときに、ハト派民主党員のクレメント・L・ヴァランディガムが、アメリカ合衆国は名誉に関わる事として捕虜の拘束を続けるという決議案を提案した。この動議は109票対16票で反対され、委員会審議に移された.[55]。政府の公式の反応はイギリスからの正式な反応を待つことになり、それが届いたのは12月18日だった。

背景[編集]

アメリカ連合国とジェファーソン・デイヴィス大統領は、ヨーロッパの繊維産業がアメリカの綿花に依存しているために、ヨーロッパ諸国の調停という形でアメリカ連合国の外交認知と仲裁に繋がると、当初から考えていた。歴史家のチャールズ・ハバードは次のように記している。 デイヴィスは外交政策を内閣の他の者に任せており、積極的な外交を行うよりも、外交的な目的を果たせる事件を期待している方だった。この新しい大統領は、綿花がヨーロッパ列強からの認知と国の正当性を保証してくれるという考え方に賭けていた。当時、アメリカ連合国の強い希望の一つは、イギリスがその繊維産業に大きな影響があることを怖れ、アメリカ連合国を認知して、北軍による海上封鎖を破ってくれるというものだった。デイヴィスが閣僚やヨーロッパ諸国に対する大使として選んでいた者達は、政治的および個人的理由によるものであり、外交的な可能性を考えたものではなかった。これはアメリカ連合国からの外交がほとんど無くても、綿花がアメリカ連合国の目的を達成してくれるという考え方があるのも理由だった[1]。

外交認知の問題︵1861年2月-8月︶[編集]

追跡と捕獲︵1861年8月-11月︶[編集]

フェアファックスはカッターでトレントに漕ぎ寄せ乗船した。拳銃とカトラス︵短剣︶で武装した20人の部隊が2隻のカッターでトレントに横付けした[25][33]。フェアファックスは、ウィルクスが国際的な事件を起こそうとしており、その範囲を拡大しようとは望んでいないことを確信していたので、その武装護衛にはカッターの中に留まるよう命令した。フェアファックスは乗船すると、怒り心頭に発するモワール船長の所に連れて行かれ、そこで﹁メイソン氏とスライデル氏および彼等の秘書官を逮捕し、捕虜として近くのアメリカ合衆国の戦闘艦に連行する﹂命令を受けていると伝えた。乗員と乗客がフェアファックスを脅したので、トレントの船腹にある2隻のカッターの武装兵はこの脅しに反応して、船腹を上り、フェアファックスを護った。モワール船長はフェアファックスの要求した乗客名簿提出を断ったが、メイソンとスライデルが前に出てきて、自分達であることを確認した。モワール船長は船内の戦時禁制品捜索も拒否した。フェアファックスはこの問題を押すことはできなかった。それは船を戦利品として捕獲する必要があったからであり、それはほぼ間違いなく戦争行為だった。メイソンとスライデルは自発的にフェアファックスと同行することを正式に拒否したが、フェアファックスの部下がカッターに誘導したときには抵抗しなかった[25][34]。

ウィルクスは後に、トレントは﹁高度に重要な積み荷を運んでおり、アメリカ合衆国にとっては有害な指示を与えられていた﹂と考えたと主張することになった。フェアファックスが船内を捜索できなかったことに加えて、外交官が携行する手荷物に文書が見つからなかったことには別の理由があった。メイソンの娘が後の1906年に記したところに拠れば、トレントの乗客だったイギリス海軍のウィリアムズ中佐がアメリカ連合国の郵袋を確保しており、後にロンドンで代表団に戻されたということである。このことはヴィクトリア女王による中立宣言に対する明らかな違反だった[35]。

国際法では、﹁戦時禁制品﹂が船上で発見されたとき、その船は最も近い捕獲審判所に裁定を求めることとされている。これがウィルクスの当初の考えだったが、フェアファックスは、サンジャシントからトレントに乗員を移せばサンジャシントが危険なくらい手薄になり、またトレントの他の乗客や郵便の受取人にとっては甚だしく不都合になるので、ウィルクスに反対した。この場の責任者だったウィルクスはフェアファックスの主張に合意し、アメリカ連合国の2人の使節およびその秘書官達を除いて、トレントがセントトマスまで進むことを認めた[36]。

サンジャシントは11月15日にバージニア州ハンプトン・ローズに到着し、ウィルクスはワシントンに使節捕獲の報せを打電した。その後ボストンに行って、アメリカ連合国の捕虜を収容する施設であるウォーレン砦に捕虜を届けるよう命令された[37]。

フェアファックスはカッターでトレントに漕ぎ寄せ乗船した。拳銃とカトラス︵短剣︶で武装した20人の部隊が2隻のカッターでトレントに横付けした[25][33]。フェアファックスは、ウィルクスが国際的な事件を起こそうとしており、その範囲を拡大しようとは望んでいないことを確信していたので、その武装護衛にはカッターの中に留まるよう命令した。フェアファックスは乗船すると、怒り心頭に発するモワール船長の所に連れて行かれ、そこで﹁メイソン氏とスライデル氏および彼等の秘書官を逮捕し、捕虜として近くのアメリカ合衆国の戦闘艦に連行する﹂命令を受けていると伝えた。乗員と乗客がフェアファックスを脅したので、トレントの船腹にある2隻のカッターの武装兵はこの脅しに反応して、船腹を上り、フェアファックスを護った。モワール船長はフェアファックスの要求した乗客名簿提出を断ったが、メイソンとスライデルが前に出てきて、自分達であることを確認した。モワール船長は船内の戦時禁制品捜索も拒否した。フェアファックスはこの問題を押すことはできなかった。それは船を戦利品として捕獲する必要があったからであり、それはほぼ間違いなく戦争行為だった。メイソンとスライデルは自発的にフェアファックスと同行することを正式に拒否したが、フェアファックスの部下がカッターに誘導したときには抵抗しなかった[25][34]。

ウィルクスは後に、トレントは﹁高度に重要な積み荷を運んでおり、アメリカ合衆国にとっては有害な指示を与えられていた﹂と考えたと主張することになった。フェアファックスが船内を捜索できなかったことに加えて、外交官が携行する手荷物に文書が見つからなかったことには別の理由があった。メイソンの娘が後の1906年に記したところに拠れば、トレントの乗客だったイギリス海軍のウィリアムズ中佐がアメリカ連合国の郵袋を確保しており、後にロンドンで代表団に戻されたということである。このことはヴィクトリア女王による中立宣言に対する明らかな違反だった[35]。

国際法では、﹁戦時禁制品﹂が船上で発見されたとき、その船は最も近い捕獲審判所に裁定を求めることとされている。これがウィルクスの当初の考えだったが、フェアファックスは、サンジャシントからトレントに乗員を移せばサンジャシントが危険なくらい手薄になり、またトレントの他の乗客や郵便の受取人にとっては甚だしく不都合になるので、ウィルクスに反対した。この場の責任者だったウィルクスはフェアファックスの主張に合意し、アメリカ連合国の2人の使節およびその秘書官達を除いて、トレントがセントトマスまで進むことを認めた[36]。

サンジャシントは11月15日にバージニア州ハンプトン・ローズに到着し、ウィルクスはワシントンに使節捕獲の報せを打電した。その後ボストンに行って、アメリカ連合国の捕虜を収容する施設であるウォーレン砦に捕虜を届けるよう命令された[37]。

北部の反応︵1861年11月16日-12月18日︶[編集]

イギリスの反応︵1861年11月27日-12月31日︶[編集]

USSジェイムズ・アジャーがサウサンプトンに到着し、マーチャンドが﹁ザ・タイムズ﹂紙からその標的がキューバに到着していたことを知ると、アメリカ連合国の使節がイギリスの船舶に乗っているとしても、必要な場合にはイギリスの海岸から見える範囲で2人の使節を捕獲するつもりだと豪語することで、そのニューズへの反応にした[56]。マーチャンドの声明によって心配の種ができたイギリスの外務省は、王室法務室の3人︵女王の弁護士、検事総長、および訴訟長官︶から、イギリスの船舶で外交官を捕縛することの合法性について法律家の見解を求めた[57]。11月12日付け文書による返答は次のようなものだった。 アメリカ合衆国の軍艦がイギリスの郵便蒸気船とイギリスの領海外で遭遇したとき︵これは内閣が提出した仮説に使われた例だった︶、郵便船を曳航し、乗船し、書類を調べ、一般の郵袋を開け、その中身を調べることができる。ただし、イギリス政府の役人あるいは部署に宛てた郵袋や小包は開けられない。 アメリカ合衆国の軍艦は西インド諸島の蒸気船に乗り組む乗員を捕獲し、アメリカ合衆国の港に連れて行ってそこの捕獲審判所の裁定を仰ぐことができる。しかしメイソン氏とスライデル氏を移動させ、捕虜として連行し、船にはその航行を続けさせるような権利は無い。[58] 11月12日、パーマストンはアダムズに、外交使節がイギリスの船舶から連れ去られた場合は抗議することを個人的に伝えた。パーマストンはアメリカ連合国の者を捕まえることが﹁考えられるあらゆるやり方の中でも非常に不適切﹂であり、イギリスにいるアメリカ連合国の者が﹁既に決められた政策を変えさせるようなこと﹂は無いと強調した。パーマストンはジェイムズ・アジャーがイギリスの領海内にいることを疑問に呈したので、アダムズは、マーチャンドに与えられた命令書を読んでおり︵マーチャンドはイギリスにいる間にアダムズを訪問していた︶、それはアメリカ連合国の船舶からメイソンとスライデルを逮捕することに限られていたと請け負った。 実際にメイソンとスライデルが逮捕されたという報せがロンドンに届いたのは11月17日になってからだった[59]。大衆の大半と新聞の多くは即座にそれがイギリスの名誉に対する許されない侮辱であり、海事法の目に余る侵犯だと認識した。﹁ロンドン・クリニクル﹂の以下の反応が典型的なものだった。 スワード氏は全ヨーロッパと喧嘩を始めようとしている。アメリカ人を誘導する意味のない利己主義という精神で、その小人の艦隊と彼等が軍隊と呼ぶ形の無いちぐはぐな部隊の集合とで、陸ではフランスと、海ではイギリスと対等であるという幻想を抱いている。[60] ロンドンの﹁標準的﹂な考え方はこの逮捕劇を、﹁この国を目標にした一連の計画的打撃の一つに過ぎない...すなわち北部州との戦争に引き込むための﹂というものだった[61]。アメリカ人訪問者からスワードに送られた手紙では、人々は怒り狂っており、投票をすれば1,000人のうち999人が即座の宣戦布告に賛成になることを怖れる﹂と記されていた。イギリス議会のある議員は、アメリカが事態を正しく処理しなければ、イギリスの国旗が﹁細かく引き裂かれて、ワシントンの大統領トイレで使われるために送られる﹂と述べていた[62]。 ﹁ザ・タイムズ﹂は12月4日にアメリカ合衆国からの最初の報告を掲載し、その通信員ウィリアム・ハワード・ラッセルはアメリカの反応について、﹁大衆の下層階級の中に大変暴力的な考えがあり、彼等は誇りと見栄で満たされているので、どんなに名誉ある譲歩でもそれを書いた人には致命的なものになる。﹂としていた[63]。しかし﹁ザ・タイムズ﹂編集者ジョン・T・ディレインは、穏健な姿勢を採り、大衆に﹁最悪の灯りの中でこの行動を見ない﹂よう警告し、リンカーン政権の初期にまで遡ってあったイギリスのスワードに対する懸念にも拘わらず、アメリカ合衆国が﹁ヨーロッパ列強と喧嘩を強いる﹂ことに意味があるかを問うように勧めた[64]。 イギリス政府はトレントに乗っていたウィリアムズ中佐がイングランド到着後直接ロンドンに来ていたので、彼から確かな情報を入手した。ウィリアムズは海軍本部で首相と数時間を過ごした。政治指導者達の最初の反応は、断固としてアメリカに対抗するものだった。元外務大臣のクラレンドン卿は、スワードが﹁喧嘩を売ろうとしており、彼が海に出て行こうと決心してもワシントンではそれが実行できないことがわかる﹂と告発して、多くの者が考えていることを表現した[65]。 ラッセルが即座の閣僚会議を要求したが、パーマストンはこれに抵抗し、再度法務室に実際に起こった出来事に基づく解説書を準備するよう要求した。緊急閣僚会議は2日後の11月29日金曜日に開催されることになった。パーマストンはまた陸軍省に、1862年の軍事予算削減は棚上げすべきことを伝えた[66]。ラッセルは11月29日にアダムズと短時間会見し、アメリカ側の意図に一筋の光明があるか判断しようとした。アダムズは、ウィルクスが命令無しに行動したと伝える手紙をスワードが既に発していたことを知らなかったので、事態を解決に導くような情報をラッセルに提供できなかった[67]。 パーマストンは緊急閣僚会議の開催に当たって、帽子をテーブルに放り出し、﹁貴方達がこの事態にどう対処するか知らないが、これは身の破滅だ﹂と叫ぶことから始めたと言われている。法務室の報告書が読み上げられ、ウィルクスの行動の違法性が確認された。ライアンズからの報告書が出席者全員に配られた。これらの報告書は、使節逮捕を支持するアメリカの興奮状態を伝えており、ライアンズが以前にスワードがこのような事件を引き起こすかもしれないと警告していた報告書に言及し、アメリカ合衆国がウィルクスが誤ったことを認める際の難しさも説明していた。ライアンズはまた、カナダに援軍を送ることを含め力を見せつけることも推薦していた。パーマストンは、この事件全体がスワードによってイギリスとの紛争を﹁引き起こす﹂ために仕組まれた﹁念入りに計画された侮辱﹂である可能性が強いことをラッセルに示した[68]。 討議が続いた後の11月30日、ラッセルはライアンズからスワードに届けさせることを意図した文書の草稿をヴィクトリア女王に送った。女王はこれを夫君のプリンス・アルバートに渡して査読を求めた。アルバートはこの後その命を奪うことになる腸チフスに罹っていたが、報告書を通読し、最後の言葉があまりに好戦的だったので、表現を和らげるように改めた。アルバートからパーマストンに宛てた11月30日付け返書には次のように書かれていた。 女王は、︵スワードに宛てた文書の中に︶アメリカの船長が指示を受けて動いたのではなく、あるいは指示を誤解して行動したのであり、アメリカ合衆国政府は、イギリス政府がその国旗を侮辱されること、および郵便の安全性が危険に曝されることを許せないことを十分に理解すべきこと、アメリカ合衆国政府が意図的にこの国に侮辱を加えようとしており、多くの悩ましい事態に加えて論争の種を押しつけているとイギリス政府は考えたくないこと、それ故にこの国を満足するに足るだけの救済策、すなわち不幸な乗客の解放と適切な謝罪を自発的に提案してくるものと考えたいという、希望の表明を入れるべきと考えている。[69] 内閣はスワードに送る公式文書にアルバートの提案を入れ、ワシントンがウィルクスの行動とイギリス国旗を侮辱する意図の双方を否定するように仕向けた。イギリスはこのとき、謝罪とアメリカ連合国使節の釈放を要求していた[70]。ライアンズ個人に与えられた指示では、スワードに7日間の返答期間を与え、満足な返答が得られない場合はワシントンの大使館を閉めて帰国するように言っていた。ラッセルは事態に対処するためのさらなる用心として、ライアンズがスワードと会って、実際に公式文書を渡す前にその内容について助言を与えるよう、私的な注意を与えた。ライアンズは、使節が釈放される限り、﹁謝罪については無くても容認できること﹂と、アダムズを通じて送られた説明で十分であることを伝えられた。ラッセルはイギリスが必要ならば戦う用意があることを繰り返し、﹁最良の解決策はスワードが解任されて、他の理性的な者が引き継ぐこと﹂を提案した。この文書は12月1日、オイローパに乗せられて発送された[71]。 軍備が進められる中で、アメリカの返事を待っていたその月の残り期間は外交が止まった。トレントの最初の報せが入って以来、イギリスの金融市場には混乱があった。その月の前半は値付けを止めたコンソル公債は2%下落し、クリミア戦争初年の水準まで行った。他の債権も4ないし5%下落した。鉄道株や植民地と外国の債券が下落した。﹁ザ・タイムズ﹂は、金融市場があたかも戦争が避けられないかのように反応していると述べた[72]。 外交官逮捕に対するイギリスの適切な反応を熟考する初期の時点で、ナポレオン3世が、アメリカとイギリスの戦争に乗じて、﹁ヨーロッパあるいは他所﹂でイギリスの利権を脅かす行動を採るのではないかという心配があった[73]。フランスとイギリスの利権はインドシナ半島、スエズ運河建設、イタリアおよびメキシコで衝突していた。パーマストンは西インド諸島でフランスが石炭を貯留していることが、フランスのイギリスに対する戦争準備を示すものと見ていた。フランス海軍は小さいままだったが、クリミア戦争のときはイギリス海軍に対抗できることを示していた。フランスが装甲艦を建造できれば、イギリス海峡における明らかな脅威になるはずだった[74]。 フランスはイギリスの疑念の多くを迅速に緩和させた。11月28日、イギリスの反応あるいはアメリカ合衆国にいるメルシエからの情報が無いままに、ナポレオンはその閣僚と会議を開いた。彼等はアメリカの行動の違法性に疑念を持たず、イギリスがどのような要求をしようとも支持することで合意した。外務大臣ソウヴネルはロンドンのシャルル・ド・フラオー伯爵に手紙を書き、イギリスに彼等の判断を知らせるように伝えた。ソウヴネルはイギリスの文書に盛られた内容を知った後、イギリス大使のカウレー卿に、その要求は完全に承認できるものであることを伝え、12月4日にはメルシエにライアンズを助けるよう指示を送った[75]。 直前までアメリカ陸軍全軍の指揮官だったウィンフィールド・スコット将軍とスワードの側近と知られたサーロー・ウィードがパリに到着したときに小さな動揺が起こった。彼等の任務はアメリカ連合国の情報宣伝に対処するに、自国の情報宣伝を行うことであり、そのことはトレント号事件より前に決まっていたことだったが、カウレーにとってはタイミングがあまりに良すぎた。スコットは、スワードがリンカーンを操作して捕虜逮捕に仕向けたことで事件の全責任がスワードにあると非難している、という噂が流れた。スコットは12月4日付け文書でこの噂を否定した。その文書はパリの﹁コンスティチュショナル﹂紙に掲載され、さらにロンドンの新聞の大半を含めヨーロッパ中で再掲された。スコットは噂を否定するときに、﹁イギリスとの友好関係保存のためならば、分別のあらゆる本能と共に良き隣人関係が我々の政府をして、栄誉ある犠牲も厭わなくさせることになる。﹂と述べていた[76]。 アメリカ合衆国の穏当な意図は、その強い支持者であり、反穀物法同盟の指導者だったジョン・ブライトとリチャード・コブデンによっても論じられていた。両人はアメリカの行動の合法性については強い留保を表明していたが、アメリカ合衆国はイギリスに対して攻撃的な意図は持っていなかったと論じた。ブライトは、この紛争がワシントンで意図的に仕組まれていたと公に発言した。12月初旬、その支持者に対する演説で、﹁我々がアメリカ政府に代表を送る前に、我々がそれに対する返事を聞く前に、︵我々が︶全て武装し、鞘から剣を抜き放ち、全ての者が拳銃やラッパ銃を点検すべきだろうか?﹂と言って、イギリスの軍備を非難した。コブデンは大衆集会での演説、および新聞、出席できない集会の組織者、さらにイギリス内外の有力者に文書を送ることで、ブライトの側に荷担した。時間の経過と共に戦争に反対する声が強くなってきたので、イギリス内閣は仲裁など戦争に代わる手段も検討し始めた[77]。軍備︵1860年12月-1861年12月︶[編集]

イギリスは南北戦争が始まる前であっても、世界的な権益のために分裂されたアメリカ合衆国に関する軍事政策を持っておく必要性があった。1860年、海軍准将アレクサンダー・ミルンが北アメリカと西インド諸島駐屯イギリス海軍の総指揮官となった。1860年12月22日、就任間もない段階でミルンが発した命令は、﹁アメリカ合衆国内部での衝突がその分裂にまで至ったとしても、アメリカ合衆国の如何なる党派にも怒りを与えるような、またはどちらかの側に党派心を表すような手段あるいは誇示﹂を避けるというものだった。1861年5月まで、ミルンはこの指示書に従い、また脱走が起こりそうな港を避けるというイギリス海軍の昔からの政策に従い、アメリカ海岸への接近を避けていた。5月13日に中立宣言が発せられた。このことでアメリカ連合国の私掠行為および北軍の海上封鎖艦艇によるイギリスの中立権に対する脅威に関心が高まったので、ミルンの部隊は補強された。6月1日、イギリスの港は拿捕した船に対して閉鎖されたので、北軍にとっては大きく有利となった。ミルンは北軍による海上封鎖の有効性を監視していたが、それを破ろうという試みが起きなかったので、11月には監視を中断した[78]。 ミルンが6月14日にライアンズから受け取った手紙には、﹁アメリカ合衆国から我々に対する突然の宣戦布告は、如何なる時にも全く起こりえないこととは見なしていない﹂と書かれていた。ミルンはその分散した部隊に警告し、6月27日には海軍省に宛てた文書で更なる援軍を要請し、西インド諸島防衛力の弱さを訴えていた。ジャマイカに関しては﹁工事の計画が悪く、お粗末に実行されている。動かない大砲、朽ちた砲架、腐食した砲弾、弾薬などあらゆる種類の倉庫の欠如、荒廃し湿った火薬庫などである﹂とその状態が報告されていた[79]。その現存部隊は商業と防衛拠点を護るだけで完全に使われてしまい、しかもその多くは不適切なままだと明らかにした。﹁突然の用に供される特殊任務の﹂艦船は1隻しか無かった[80]。 イギリス陸軍の場合、1861年3月末時点で、ノバスコシアに正規兵2,100名、カナダの残り部分、ブリティッシュコロンビア州、バミューダおよび西インド諸島に散開した基地で2,200名が配置されていた。カナダ副総督で北アメリカ総司令官のウィリアム・フェンウィック・ウィリアムズはその小部隊でできることを行ったが、イギリス当局に繰り返し手紙を書いて、その防衛を適切にするためにかなりの援軍を必要とすることを訴えていた[81]。 5月と6月に幾らかの陸軍増援が派遣された。しかし海上封鎖とバンチ事件で警告を受けたパーマストンが、カナダにおける正規兵を1万名まで増強しようとすると、抵抗に遭った。陸軍省長官であるジョージ・コーンウォール・ルイスは、イギリスに対する実際の脅威があるのか疑問を呈した。ルイスは、﹁通常の了見を持った政府が、内戦にあたってその敵の数を無分別に増やしたり、さらにはイギリスのような恐ろしい敵に敵対するのは信じがたい﹂と判断した。6月21日に議会で行われた議論では、政治的、軍事的および経済的に見て、総論は増援に反対だった。これ以前からカナダの防衛は地元政府の負担に移すべきだという試みが、議会で議論されていた。植民地担当大臣のニューカッスル公爵は、ウィリアムズによる増援要請が﹁過去数年間﹂続いていたものの一部だと考え、その間にも大変多くの要求や提案を受けていた。ニューカッスル公爵は増援に対する冬季宿舎が不足して居ることも心配であり、脱走が深刻な問題になることを怖れていた[82]。 海軍省長官のサマセット公爵は、パーマストンがミルンの補強に動いていることに反対した。サマセットは現存部隊の大半が蒸気船で構成されており、北軍の主要帆船よりも優勢であると考え、イギリスがその艦隊を鋼鉄船に造り替えているときに、余分な費用を掛けることを躊躇っていた。この議会と内閣からの抵抗について、歴史家のケネス・ボーンは﹁それ故に、トレントの侵害に関する報せがイギリスに届いたとき、イギリスは、北部が譲らなかったときにほとんど誰もが避けられないと合意するであろう戦争に対する備えがまだ適切でなかった﹂と結論づけることになった[83]。 トレント号事件の初めからイギリス指導層は、軍事的な選択が国益を守るための基本であることに気付いていた。海軍省長官は、アメリカ合衆国からの厳しい攻撃にはカナダを守れないことと、それを後に回復させるのは難しく費用も掛かることになると考えていた。ボーンは、﹁1815年以降の米英関係の曖昧さの中で、庶民院の倹約癖と実行に伴う大きな困難さのために、米英戦争に対する適切な備えが常にできなかったように見える。﹂と記した[84]。サマセットは陸上での戦争よりも海上での戦争を提案した[85]。 イギリス領インドは北軍の火薬に使われる硝石の主要産地だった。ラッセルはトレント号事件を知ってから数時間のうちに、硝石の輸出を停止させることに動いた[86]。トレント号事件の報せがイギリスに届いてからは迅速に軍備が始まった。陸軍長官ジョージ・コーンウォール・ルイスは﹁ライフル3万挺、砲兵1個大隊、および数人の士官をカナダに﹂1週間以内に送る提案をした。12月3日にはパーマストンに宛てて、﹁キュナード蒸気船を使い、来週歩兵1個連隊と砲兵1個大隊を派遣することを提案する﹂、その後できるだけ早く歩兵3個連隊と多くの砲兵を送ることも提案すると記した文書を送った[87]。しかし、この時の北アメリカは冬に入っていたので、セントローレンス川は凍り始めており、援軍はノバスコシアに上陸させることとされた。 ラッセルはルイスとパーマストンがあまりに早く行動して、ある筈の和平のチャンスを取り逃がしてしまうことを心配し、﹁ルイスとサマセット公爵を支援するための小さな委員会﹂で作戦計画を立てることを要請した。この委員会は12月9日に創られて招集された。委員はパーマストン、ルイス、サマセット、ラッセル、ニューカッスル、グランビル︵外務大臣︶およびケンブリッジ公︵イギリス陸軍総司令官︶で構成され、グレイ伯爵︵ルイスの次官︶、シートン卿︵元カナダ総司令官︶、ジョン・フォックス・バーゴイン将軍︵要塞化総括監察官︶およびP・L・マクドゥーガル大佐︵元カナダライフル隊指揮官︶が顧問となった。委員会の第1課題はカナダの防衛であり、この問題について以前に立てられた作戦と、専門家の証言から委員会が組み立てた情報とに依存することになった[88]。 当時のカナダには、5,000名の正規兵とほぼ同数の﹁訓練されていない﹂民兵がおり、その民兵の5分の1だけが組織化されていた。イギリスは12月中に18隻の輸送船を使って11,000名の部隊を送ることができ、12月末までにさらに28,400名を派遣する用意ができていた。危機が去った12月末、5万名から20万名と予測されたアメリカ軍の侵略に対し、士官924名と兵卒17,658名が援軍として到着していた[89]。 カナダではウィリアムズ将軍が11月と12月に使える砦や要塞を回った。歴史家のゴードン・ウォーレンは、ウィリアムズが﹁砦は朽ち果ているか存在しないかであり、それに必要な修復工事量は想像も付かない﹂ことが分かったと記した[90]。12月2日、ウィリアムズの要請でカナダ政府は現役の志願兵を7,500名まで増やすことに合意した。カナダ法では定住民兵が可能であり、それは16歳から50歳までの全ての男性で構成されていた。ボーンは定住民兵とカナダの民兵隊の状態について次のように記していた。 その誇るべき記録にも拘わらず、あるいはそれ故に、カナダ民兵隊は単なる紙の軍隊になってしまっていた。法によって18歳から60歳までの男性は全て従軍すべきものとされているが、その大多数は定住民兵であり、登録されているに過ぎない。唯一活動している軍隊は志願兵のものであり、軍務管理所に拠れば年に6日ないし12日の訓練を受けているだけである。登録許可された5,000名のうち、1861年時点では4,422名に過ぎなかった。ニューカッスルは﹁惨めな小軍隊だ!その多くは去年から大きく改善されて居なければ、訓練されていないに等しい﹂と言っていた。[91] 12月20日、ウィリアムズは総計約38,000名になった定住民兵の各大隊から選抜した75名の1個中隊の訓練を始めた[92]。ウォーレンは定住民兵について次のように表現している。 訓練されず規律もない彼等は、あらゆる形の服装をしており、アメリカボダイ樹の皮のベルトもあれば、帽子にはミドリのバルサムの枝もあった。火打ち石銃、散弾銃、ライフル銃および大鎌と武器も様々だった。その士官は命令の前に﹁プリーズ﹂を付け、左旋回のコマンドに田舎者の隊列がジグザグになったとしても、恐ろしくなって怯んでいた。[92] ウィリアムズの任務は南北戦争が始まったときに北軍と南軍が直面したものと大差はなかった。カナダ総督のチャールズ・モンクは、4月までにその地域から総計10万名の部隊を動員できると考えた︵イギリスが武装の大半を供給するものと仮定した︶。その数字はニューカッスルによってイギリス軍がカナダで当時利用できると予測したものだった[93]。 軍事基本計画が立てられたのは、概して準備の足りなかったカナダの軍事事情の範囲内でのことだった。その作戦は1862年春まで利用可能とはならない部隊を元にしていた[94]。カナダはアメリカ合衆国との戦争の備えができていなかった[95]。戦時内閣の中では、北軍が戦争を中断してカナダに全力を向けると考えたマクドゥーガル大佐と、戦争が続くと考えるバーゴイン将軍の間に意見の不一致があった。しかし、両者はカナダがアメリカ合衆国からの大きな陸戦に直面し、その攻撃には抵抗するのが難しいということでは一致していた[96]。防衛は﹁要塞の幅広い体系﹂と﹁五大湖の支配権の確保﹂に掛かっていた。バーゴインは強力な要塞で守りの姿勢で戦う戦術的長所を強調したが、以前に創られた要塞化の計画は実行されることが無かったのも事実だった。五大湖では、カナダもアメリカ合衆国も11月時点で海軍力を備えていなかった。ここでは1862年春までイギリス軍は脆弱なままだった[97]。 アメリカからの攻勢に対して弱いことの代案として、カナダからアメリカ合衆国を侵略する案が提案された。ポートランドとメイン州の大半の占領に成功すれば、アメリカ合衆国東西の通信線と輸送線に沿ってカナダ侵略に使う戦力を分散できることになると考えられた。バーゴイン、シートンおよびマクドゥーガルがこの作戦を全て支持し、ルイスは12月3日にパーマストンに提案した。しかしこの攻撃の準備が行われることはなく、その成功可能性は開戦当初に始められる攻撃に依存することになった[98]。マクドゥーガルは﹁カナダへの併合を望む集団がメイン州に存在すると考えた︵ボーンは疑念を挟んでいる︶。この集団がイギリスによる侵略を助けてくれるはずだった。海軍の水路測量技師ワシントン船長とミルンの両者は、そのような集団が存在するならば、攻撃を延長して、﹁メイン州がその所属を変えたい﹂ということが明らかになるまで待つのが最善だと考えた[99]。 ﹁ザ・タイムズ﹂がカナダの軍事力について上に上げた数字とは異なる数字を報告していることは注目すべきである。﹁ザ・タイムズ﹂は38,000名の備えのない民兵ではなく、66,615名の民兵と志願兵からなる民兵軍があり、﹁アメリカ合衆国が振り向けられる勢力にあらゆる面で引けを取らない﹂としていた[100]。﹁ザ・タイムズ﹂はまた、1862年2月10日に、105,550名の武器と装備が、2,000万の銃弾と共にカナダに到着したと報じた[101]。 モントリオール特派員より、12月23日、この時点までにカナダではその国土侵略に対抗するために武装した6万名がいることになった。1か月前ならカナダは敵の餌食だった。1か月経って寸分の隙もなく武装し、冬の間にもたらされる可能性のある如何なる軍隊にも堅いも守りを発揮できるようになった。[102] 志願兵や民兵の大隊がイギリス領北アメリカ︵すなわち、現代のオンタリオ州とケベック州の南側3分の1に相当するカナダ、ニューブランズウィック州、ノバスコシア州、プリンスエドワード島およびニューファンドランド島であり、現在のニューファンドランド・ラブラドール州にあるニューファンドランド島の大半は含んでいなかった︶に動員できたかはさておき、1862年に︵1861年では動員できなかった︶、実際にイギリス軍が動員できた戦力は次の通りだった。 ●1860年 - 歩兵4個大隊、要塞砲兵4個大隊 ●1861年7月の増強 - 歩兵3個大隊、野砲兵1個大隊、および現存する駐屯地から派遣できる勢力 ●トレント号事件による補強 - 歩兵9個大隊、野砲兵5個大隊、要塞砲兵8個大隊、工兵3個中隊、その他支援任務部隊と本部参謀 1862年初めの勢力は歩兵14個大隊︵1個大隊の一部および本部参謀の一部は北大西洋の冬のためにノバスコシアに上陸できなかった。参謀はボストンに上陸し、陸路アメリカ合衆国の中を抜けてモントリオールに向かった︶、野砲兵6個大隊、要塞砲兵12個大隊、工兵3個中隊、およびその他支援任務部隊だった[103] 。 上記の中で、歩兵5個大隊、野砲兵3個大隊、要塞砲兵6個大隊は海上をノバスコシア州ハリファックスからニューブランズウィック州セントジョンに移動し、そこから陸路橇を使ってカナダのリビエール・ドゥ・ルーに移動した。期間は1862年1月1日から3月31日だった。10日間の陸路搬送とリビエール・ドゥ・ルーからビル・ドゥ・ケベックまでの鉄道は国境から1日の行程にあった︵ある場所ではアメリカ合衆国メイン州からライフル銃の射程内にあった︶。イギリス軍参謀は必要な場合に歩兵に道路を守らせる配置を計画した。陸路を進んだ部隊と、既にカナダにあったイギリス軍を含め、1862年3月までにイギリス軍野戦部隊は歩兵9個大隊と野砲兵4個大隊になるはずであり、これは3個旅団︵すなわち1個師団︶に相当していた。ニューブランズウィック州とノバスコシア州の間には2個旅団以上の勢力があった[104]。 比較のためにアメリカ合衆国は1861年4月に動員を始めており、最初は3か月の短期間徴兵75,000名が招集された。その後、長期間徴兵︵24か月ないし36か月︶50万名の呼びかけが7月に行われた。1861年12月31日までに公式記録では42万5,000名が﹁現役任務﹂でその部隊と共にあり、その他に一時的な﹁特別あるいは日雇い﹂任務、病気あるいは逮捕中として挙げられた52,000名がいた[105]。これらの兵士は連隊、旅団および師団に組織化され、師団は3個旅団︵それぞれ3ないし4個歩兵大隊︶と3ないし4個の師団付き砲兵大隊から構成された。師団は1861年に組織化され︵最初のものは7月のポトマック軍バンクス師団︶、1862年1月までに、ポトマック軍に13師団、バージニア州西部に2個、メリーランド州に1個︵バーンサイド︶、サウスカロライナ州に1個︵シャーマン︶、オハイオ軍に5個、ミズーリ州とテネシー州に各1個が配備された。総計は24個師団となった。この総計には、別の旅団レベルの部隊、メイン州からカリフォルニア州までの様々な要塞や基地の守備隊は含まれていない。追加師団は1862年に組織化された。 イギリスが最大の力を持っており、必要ならばアメリカ合衆国と戦える能力があったのは海上だった。12月1日、海軍省はラッセルに宛てて、ミルンが﹁アメリカ、西インド諸島およびイギリスの間の貴重な貿易を保護するために必要と考えられる手段に特別の注意を払うべき﹂と書き送った。しかし、サマセットは世界中のイギリス海軍戦隊に、アメリカの船舶を見つけ次第攻撃できる準備をするよう暫定命令を発した。内閣は厳密な海上封鎖を敷き維持することがイギリスの成功にとって不可欠であることにも合意した[106]。 1864年にミルンはその作戦を以下のように記した。 我々の基地、特にバミューダとハリファックス市を確保するために、当時ダンロップ代将の指揮下にあったメキシコの戦隊と私の指揮下にあったバミューダの戦隊で南部の港を封鎖し、続いて即座に私の戦隊で北部主要港を封鎖し、さらに南部の戦隊と協業してチェサピーク湾を封鎖する。[107] アメリカ連合国との共同作戦の可能性について、サマセットはミルンに宛てて12月15日に次のように書き送っていた。 概して、ワシントンあるいはボルティモア攻撃のような見かけでの作戦で、大規模な共同作戦の可能性は避けた方が良い︵艦隊が関わる可能性がある場合は除く︶。経験から異なる国の軍隊が共同作戦を行うときは常に大きな悪魔が潜んでいる。この場合に防御側の敵の利点は、それに対する部隊の統合を補う以上のものがある。[108] サマセットは要塞化された基地に攻撃することに反対し、ミルンも次のように賛同していた。 戦争の目的は勿論敵の戦力を無能にするためとのみ考えられる。それが任務であり、その任務の中でも船舶が重要である。現代の見解は町に与える損傷を軽視しているので、砦だけが攻撃されるのであれば目的は達せられない。船舶が港で砲撃されれば、町も被害を受けるに違いない。それ故に船舶に砲撃されないではおけない。このことは実際に海上での船舶に対する作戦に匹敵する。町が守られていなかったり、守りが屈するならば、通商禁止令が布かれ、上納金が要求される[109] イギリスはアメリカよりも海軍力が優れていると確信していた。北軍が持っている船舶量はミルンの動員可能な戦力を上回っていたが、北軍の艦隊の多くは単に改装された商船であり、イギリス海軍は使える大砲の量では勝っていた。ボーンは、両軍が装甲艦への移行を進めたので、この長所が戦争の間に変化しえたと述べている。特にイギリスの装甲艦は喫水が深く、アメリカの海岸線では操船できなかったので、アメリカの装甲艦に対して木造帆船で海上封鎖するのは難しくなっていた[110]。 勿論軍事的な選択肢は必要とされなかった。もしされていたならば、﹁17世紀から18世紀に続いたイギリスの世界支配は消失していただろう。イギリス海軍はかつてなく強力だったが、もはや時流には逆らえなかった。﹂とウォーレンが結論づけている[111]。軍事史家ラッセル・ウェイグリーはウォーレンの分析に同意し、次のように付け加えている。 イギリス海軍は、海軍の空白期に存在し、フランスから半ば乗り気でない散発的な挑戦を受けていたこと以外重大な競争相手がいなかったので、外見的には海上の優越性を保持していた。当時、イギリス海軍は北アメリカ海岸でその力を行使する難しさを感じていたであろう。蒸気船の出現で、1812年の米英戦争で海上封鎖戦隊が行ったように、アメリカの水域をその最良の戦艦が無条件に巡航する能力が無くなっていた。ハリファックスに主要基地があり、アメリカ連合国からの支援があったとしても、イギリス海軍はアメリカ合衆国海岸に基地を保持することが危なっかしいものであることが分かった筈である。イギリス艦隊に大西洋を渡る戦争を強いたとすれば、母港から遠く離れた海域でかなり強力な敵と対戦することになり、蒸気船の海軍でそのような成功例は無かった。アメリカ海軍が第二次世界大戦で日本と戦って成功したのが最初の事例である。[112] 1862年2月、イギリス陸軍総司令官ケンブリッジはトレント号事件に対するイギリスの軍事対応に関して異なる分析を行っていた。 我々は戦争を開始するところまで行かなかったが、その能力を誇示できなかったことを残念に思わない。アメリカと世界全体にとっては貴重な訓練になったであろうし、そうする必要性が生じた場合は、イギリスが何をでき何をするかを示したことだろう。われわれは、ある人々がやりくりできると考えるようなそれほどの軍事力をもっておらず、今の我々の軍事組織はいつでも戦えるし、危急のときに備えているというようなものであるという事実も明らかにした。また我々は困難に任務を扱える有能な人員がいることも証明している。[113]解決︵1861年12月17日-1862年1月14日︶[編集]

1861年12月17日、アダムズはスワードの11月30日付け文書を受け取った。それにはウィルクスが命令無しに行動したことが記されており、アダムズは即座にそれをラッセルに告げた。ラッセルはこの報せに勇気づけられたが、イギリスからの文書に対する正式な返信があるまで行動は採らなかった。この報せは公開されなかったが、北軍の意図についての噂が新聞に掲載された。ラッセルはその情報の確認を拒み、ジョン・ブライトは後に議会に﹁この文書がこの国の人々に与えられる情報として公開されないのはどういうことか?﹂と質問した[114]。 ワシントンでは、ライアンズが12月18日に公式文書と彼への指示書を受け取っていた。ライアンズは支持通りにスワードと12月19日に会見し、イギリスの反応の内容を説明したが、実際に文書は渡さなかった。スワードは公式文書を受け取ってから7日以内に正式な返書を発することを期待されていると告げられた。スワードの要請によってライアンズはイギリス文書の非公式写しを渡し、スワードは即座にそれをリンカーンに見せた。12月21日土曜日、ラインズがスワードを訪問して﹁イギリスの最後通告﹂を渡したが、いろいろ議論したあとで、正式な手交はさらに2日後ということで合意された。ライアンズとスワードは、7日間という期限がイギリス政府からの公式文書の一部であると考えるべきではないということで合意した[115]。 上院外交委員会委員長であり、外交問題ではリンカーン大統領顧問を務めることの多かったチャールズ・サムナー上院議員は、即座にメイソンとスライデルを釈放する必要があることを認識していたが、民衆が興奮状態である間は沈黙を保っていた。サムナーは過去にイギリスに旅し、イギリスの政治的な活動家と定期的な文通を行っていた。12月にはリチャード・コブデンとジョン・ブライトから特別な警告を伝える手紙を受け取っていた。ブライトとコブデンは政府の戦争準備状況と、ウィルクスの行動の合法性に関して自分達のものを含め世間に広まる疑惑を論じていた。イギリスにおける強硬な反奴隷制度論者のアーガイル公爵夫人は、使節の逮捕が﹁かつてない狂気の行動であり、︵アメリカ合衆国︶政府が戦争を強いるつもりで無ければ、全く考えられないこと﹂とサムナーへの手紙で知らせていた[116]。 サムナーはこれらの手紙を持って、イギリスの公式要求を知ったばかりのリンカーンのところへ行った。サムナーとリンカーンは翌週毎日のように会見して、イギリスとの戦争から来る影響を論じあった。12月24日、サムナーは、イギリスの艦隊が北軍の海上封鎖を破って独自の封鎖を行うこと、フランスがアメリカ連合国を認知しメキシコやラテンアメリカで活動を行うこと、戦後︵アメリカ連合国が独立したとして︶南部を通じてイギリス製造業の密貿易が広がればアメリカの製造業を破壊することといった心配事を記した。リンカーンは直接ライアンズと会見できると考え、﹁私が心から平和を望んでいることを彼に5分間でも示す﹂と言ったが、サムナーはそのような会見の外交的不適切さを説明した。両人は調停が最善の解決策であるという合意に至り、サムナーはクリスマスの朝に予定されている閣僚会議への出席を要請された[117]。 閣僚会議の時までにヨーロッパからの関連情報がワシントンに入っていた。12月25日、アダムズが12月6日付けで発信した手紙がワシントンに届き、それには以下のように書かれていた。 この国の感情は燃え上がっており、もしこの報せが対岸に届く前にアメリカ合衆国政府が説明の可能性を排除するやり方でウィルクス船長を支持するようなことがあれば、衝突は避けられない。...もはや︵イギリスの︶閣僚や人民は、敵対関係を進めているのはアメリカ合衆国政府の意志であると信じている。[118] これと同時にイギリスに駐在する2人のアメリカ領事からの文書も届けられた。マンチェスターからは、イギリスが﹁大きな活力を持って﹂軍備を進めているという報せ、ロンドンからは﹁強力な艦隊が﹂日夜を挙げずして建造されているという報せだった。パリからロンドンに移動したサーロウ・ウィードは、スコット将軍の文書が広まっていることを確認し、スワードに宛てて﹁このように迅速で巨大な軍備は知らない﹂と記した手紙を送った[119]。 全てが否定的な報せと共にフランスからの公式反応も届いた。デイトンは既にソウヴネルとの会見の模様をスワードに伝えており、その中でフランスの外務大臣が、ウィルクスの行動は﹁明らかに国際法の侵犯﹂であるが、フランスは﹁アメリカ合衆国とイギリスとの間の戦争では傍観者に留まる﹂と伝えていた[120]。ソウヴネルから直接の文書がクリスマスの日に届き︵実際に閣僚会議の最中に配達された︶、捕虜の解放と、そうすることでフランスとアメリカ合衆国がイギリスに対して繰り返し主張してきた海上における中立国の権利を確認することを勧めていた[121]。 スワードは閣僚会議の前にイギリスに対する公式返書の草稿を準備しており、詳細で組織だった立場を持っていた唯一の出席者だった。スワードの主要論点は、捕虜の釈放が中立国の権利に関するアメリカの伝統的な姿勢に一致することであり、大衆もこれを認めるはずだということだった。チェイスと司法長官のエドワード・ベイツはヨーロッパからの様々な伝言に強い影響を受けており、郵政長官のモンゴメリー・ブレアはこの会議の前であっても捕虜の釈放に賛成していた。リンカーンは調停に固執したが、その支持は得られず、当座の対象は事件に巻き込まれイライラしているイギリスだということになった。この会議で結論は出ず、翌日の会議に持ち越された。リンカーンは翌日に自身が作った文書を用意したいと表明した。翌日スワードの捕虜釈放提案は反対意見無しに承認された。リンカーンは反論をせず、後にスワードに、スワードの姿勢に対する説得力ある反論を書けないことが分かったと教えた[122]。 スワードの返書は﹁長く、高度に政治的な文書﹂だった[123]。スワードは、ウィルクスが自分の意志で行動し、逮捕自体が不躾で暴力的に行われたというイギリスの主張を否定したと述べた。トレントの捕獲と捜索は国際法に則ったものであり、ウィルクスの犯した唯一の誤りはトレントを司法権限のある港に曳航できなかったことにある。それ故に﹁我々が常に我々に対して全ての国がすべきと主張していることをイギリスに対して行う﹂ために捕虜釈放が求められる。スワードの返書は実際に、ウィルクスの捕虜に対する待遇が戦時禁制に対するものであると認め、その捕獲はイギリスが中立国の船舶からイギリス市民を強制徴用することと同等だとしていた[124]。 ライアンズは12月27日にスワードの事務所に呼ばれ、返書を渡された。スワードの述べた事件に関する分析よりも、捕虜釈放に重点を置いたライアンズは返書をロンドンに回送し、次の指示があるまでワシントンに留まることにした。捕虜釈放の報せは12月29日に新聞に掲載され、大衆の反応は概して肯定的だった。この判断に反対した者の中にウィルクスがいた。ウィルクスは﹁彼等の逮捕によって行われた意気地の無い屈服とあらゆる善の放棄﹂だと述べた[125]。 メイソンとスライデルははウォーレン砦から解放され、マサチューセッツ州プロビンスタウンでイギリス海軍のスクリュー推進スループ船HMSリナルドに乗船した。彼等リナルドでセントトマスに行き、1月14日にイギリスのサウサンプトンに向かう郵便船ラプラタに乗り換えた。釈放の報せは1月8日にイギリスに届いた。イギリスはこの報せを外交の勝利として受け取った。パーマストンは、スワードの返書にはイギリスの解釈とは異なる﹁国際法の多くの原則﹂が入っていると述べ、ラッセルはスワードに宛ててその法解釈に異議を唱える詳細な文書を送ったが、事実上危機は回避された[126]。事件の後[編集]

歴史家のチャールズ・ハバードは危機の解決にあたってアメリカ連合国の考え方を次のように説明している。 トレント号事件の解決はアメリカ連合国の外交にとっては重大な打撃だった。まず、1861年の夏から秋に進んでいた外交認知の動きを止めさせた。イギリスでは、アメリカ合衆国が必要な場合は自国を護る用意があるが、国際法を守る責任を認識しているという考え方が生まれた。さらに、イギリスとフランスでは、アメリカの交戦状態に関して、ヨーロッパ諸国が中立を守る限り、平和が保たれるという考えも生まれた。[127] アメリカ連合国の外交認知の問題は残っていた。この問題は1862年を通じてイギリスとフランスの政府で検討され、調停案として正式に提案するものであり、拒むのは難しいという筋書きだった。アメリカでの戦争が激化し、シャイローの戦いでの血生臭い結果が知られると、人道的な理由でヨーロッパ諸国による干渉が一理あると見られるようになった[128]。しかし、1862年9月に公表された奴隷解放予備宣言によって、奴隷制度の問題がこの戦争の中心課題であることが明らかにされた。アンティータムの戦いと奴隷解放予備宣言に対する当初のイギリスの反応は、戦争自体がより激しさを増す中で、南部の中での奴隷反乱を生むだけだというものだった[129]。1862年11月になってヨーロッパ諸国による干渉の動きは尻すぼみになった[130]。脚注[編集]

- ^ Hubbard pg. 7. Hubbard further writes that Davis’ policy was “a rigid and inflexible policy based on economic coercion and force. The stubborn reliance of the Confederates on a King Cotton strategy resulted in a natural resistance to coercion from the Europeans. Davis’s policy was to hold back cotton until the Europeans “came to get it.” The opinions of Secretary of War Judah Benjamin and Secretary of the Treasury Christopher Memminger that cotton should be immediately exported in order to build up foreign credits was overridden by Davis. Hubbard pg. 21-25

- ^ Jones pp. 2–3. Hubbard p. 17. Mahin p. 12.

- ^ Berwanger p. 874. Hubbard p. 18. Baxter, The British Government and Neutral Rights, p. 9. Baxter wrote, “the British government, while defending the rights of British merchants and shipowners, kept one eye on the precedents and the other on the future interests of the mistress of the sea.”

- ^ Graebner p. 60–61.

- ^ Mahin p. 47. Taylor p. 177.

- ^ Mahin p. 7. Mahin notes that Seward had talked in the 1850s of annexing Canada and in February 1861 had spoken frequently of reuniting the North and South by a foreign war.

- ^ Dubrulle pg. 1234.

- ^ Donald, Baker, Holt pp. 311–312. Hubbard pp. 27–29

- ^ Jones pp. 3–4, 35.

- ^ Hubbard pp. 34–39. Walther p. 308. Russell had written to Lyons about the arrival of the three Confederates: “If it can possibly be helped, Mr. Seward must not be allowed to get us into a quarrel. I shall see the southerners when they come, but unofficially, and keep them at a proper distance.” Graebner p. 64.

- ^ Mahin p. 48. Graebner p. 63. Donald, Baker, Holt p. 312.

- ^ Mahin pp. 48–49. Hubbard p. 39. Jones p. 34

- ^ Donald, Baker pg. 314. Mahin pg. 48-49. Taylor pg. 175-179. Taylor notes that British officials already believed that Seward would provoke an international crisis as a diversion from the Union’s internal problems. For example, an article in the New York Times, believed to have been planted by Seward in order to transmit a warning to Britain, had said that any permanent dissolution of the Union would invariably lead to United States acquisition of Canada.

- ^ Mahin pg. 54-55. The negotiations between the United States and Britain failed when Lord Russell, aware that the treaty would obligate the British to treat Confederate privateers as pirates, informed Adams on August 19, 1861 that, “Her Majesty does not intend thereby to undertake any engagement which shall have any bearing, direct or indirect, on the internal differences now prevailing in the United States.”

- ^ Berwanger, pp 39-51

- ^ Mahin pg. 54-56. Hubbard pg 50-51.

- ^ Warren pg. 79-80.

- ^ Mahin pg. 98.

- ^ Mahin pg. 96-97.

- ^ Walther pg. 316-318. Hubbard pg. 43-44, 55. Monaghan pg. 174. Monaghan notes that as the news of the Trent Affair reached London, Russell made the following reply to written correspondence from the Confederate commissioners, “Lord Russell presents his compliments to Mr. Yancey, Mr. Rost, and Mr. Mann. He has had the honor to receive their letters of the 27th and 30th of November, but in the present state of affairs he must decline to enter into any official communication with them.”

- ^ Mahin pg. 58. Hubbard pg. 58

- ^ Weigley pg. 78. Weigley suggests an interesting alternative hypothesis to the traditional narrative of events when he writes, “The Confederate government may have intended the Mason-Slidell mission as a trap to bring the United States and Great Britain to war. The itinerary of the two emissaries was suspiciously well advertised. At Havana, they fraternized and dined with the officers of the San Jacinto, again publicizing their departure plans. On board the Trent, Slidell appeared unduly eager to become a captive.”

- ^ Hubbard pg. 60-61. Mahin pg. 58. Musicant pg. 110.

- ^ Musicant pg. 110-111

- ^ a b c d http://h42day.100megsfree5.com/histanex/11anxs/08trent.html

- ^ Musicant pg. 110-111. Mahin pg. 59

- ^ Musicant pg. 111. Monaghan pg. 173

- ^ Mahin pg. 59. Donald, Baker, Holt pg. 315. Ferris pg. 22. Wilkes later said that he had consulted “all the authorities on international law to which I had access, viz, Kent, Wheaton and Vattel, besides various decisions of Sir William Scott and other judges of the Admiralty Court of Great Britain.” Musicant pg. 111. Musicant notes that the availability of the law texts on San Jacinto were the result of the complex legal situations that were likely to have been encountered in its two year anti-slave-trade patrol of the African coast.

- ^ Donald, Baker, Holt pg. 314

- ^ Mahin pg. 59

- ^ Nevins pg. 387-388

- ^ Fairfax pg. 136-137

- ^ Fairfax pg. 137

- ^ Fairfax pg. 137-139. Ferris pg. 23-24

- ^ Mahin pg. 60. Ferris pg. 22. Monaghan pg. 167. Williams was the only British naval officer involved in the incident.

- ^ Mahin pg. 61. Ferris pg. 25-26. Fairfax pg. 140. Fairfax adds the following in his account of the proceedings, “I gave my real reasons some weeks afterward to Secretary Chase, whom I met by chance at the Treasury Department, he having asked me to explain why I had not literally obeyed Captain Wilkes's instructions. I told him that it was because I was impressed with England's sympathy for the South and felt that she would be glad to have so good a ground to declare war against the United States. Mr. Chase seemed surprised, and exclaimed, ‘You have certainly relieved the Government from great embarrassment, to say the least.’”

- ^ Mahin pg. 61

- ^ Ferris pg 32-33. Jones pg. 83. Jones wrote, “The seizure of these two Southerners in particular drew a triumphant response. Mason had been a principle (sic) advocate of the hated Fugitive Slave Law and the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and Slidell had earned a reputation as one of the most dedicated secessionists in Congress.” Charles Francis Adams Jr. pg. 541. Charles Francis Adams Jr., son of the U. S. Minister to Great Britain, wrote, “Probably no two men in the entire South were more thoroughly obnoxious to those of the Union side than Mason and Slidell.”

- ^ Ferris pg. 33-35

- ^ Charles Francis Adams Jr. pg 548-549

- ^ Charles Francis Adams Jr. pg. 547

- ^ Charles Francis Adams Jr.pg. 548

- ^ Charles Francis Adams Jr. pg. 548.

- ^ Ferris pg. 34.

- ^ Jones pg 83.

- ^ Jones pg. 89.

- ^ Ferris pg. 35-36

- ^ Donald, Holt, Baker pg. 315

- ^ Nevins pg. 392-393. Jones pg. 89

- ^ Mahin pg. 62. Nevins pg. 392-393.

- ^ Mahin pg. 64. Warren pg. 170-171

- ^ Warren pg. 173.

- ^ Niven pp. 270-273.

- ^ Jones pg. 88. Warren pg. 174-175.

- ^ Warren pg. 175-176.

- ^ Mahin pg. 64-65. Nevins pg. 389. The Nashville had captured and destroyed the Union merchant ship Harvey Birch on its trip. Adams tried to have the ship declared a pirate. British authorities held it briefly in port, but by November 28 Russell had determined that she was properly documented as a CSA warship, and its officers were properly credentialed by the CSA. Ferris pg. 37-41

- ^ Mahin pg. 65

- ^ Baxter, “Papers Relating to Belligerent and Neutral Rights, 1861-1865 pg. 84-86. Warren pg. 96-97. Warren writes that at a cabinet meeting on November 11 Lord Chancellor Richard Bethell, an Admiralty judge for twenty three years, and Dr. Stephen Lushington, a judge on the High Court of the Admiralty, both argued that simply removing the envoys would not have been a violation of international law.

- ^ Donald, Baker pg. 316. Mahin pg. 25.

- ^ Donald, Baker, and Holt pg. 315

- ^ Warren pg. 107

- ^ Warren pg. 105.

- ^ Mahin pg. 69

- ^ Warren pg. 106-107

- ^ Warren pg. 109

- ^ Ferris pg 44

- ^ Warren pg. 109.

- ^ Jones pg. 84-85. Ferris pg. 52. Mahin pg. 69. Lyons, in a private letter, reported to Palmerston that (although he could not “vouch for the truth” of his source) he had heard that unbeknownst to Lincoln, Seward had directly ordered the capture by Wilkes. Mahin pg. 70.

- ^ Mahin pg 68-69

- ^ Jones pg. 85.

- ^ Ferris pg. 52- 53.

- ^ Warren pg. 146-147

- ^ Ferris pg. 76. Clarendon in September, anticipating the U.S. would pick a fight with Britain wrote that he felt “N[apoleon] w[oul]d instantly leave us in the lurch and do something in Europe w[hic]h we can’t stand.”

- ^ Warren pg. 85.

- ^ Ferris pg. 79.

- ^ Ferris pg. 80-84.

- ^ Warren pg. 149-152.

- ^ Baxter, The British Government and Neutral Rights pg. 10-12.

- ^ Baxter, The British Government and Neutral Rights pg. 14

- ^ Bourne pg 601

- ^ Bourne pg. 601

- ^ Bourne pg. 602-605

- ^ Bourne pg 604-605

- ^ Bourne pg. 600

- ^ Ferris pg. 63

- ^ Donald, Holt,Baker pg. 316. Ferris pg 62

- ^ Ferris pg 64

- ^ Ferris pg. 64. Warren pg. 133. Bourne pg. 607.

- ^ Warren pg. 132-133. Mahin pg. 72. Ferris pg. 65. Ferris indicates in footnote no. 30 on page 219 that his account is based largely on Bourne who “is the only scholar, I believe, who has examined most of the pertinent archival sources.”

- ^ Warren pg. 134. Warren further wrote, “At Toronto and Kingston, he proposed earthworks with heavy ordnance, and allocated two hundred men for extending and strengthening them. A new ten-gun battery was to replace the rusty cannon overlooking the Grand Trunk Railway tracks, wharf, and channel, and a Royal Artillery officer arrived to instruct men in its use. Williams wanted to blow bridges over the St. Lawrence and, in the event of attack, close Toronto by sinking ships. Desperate moves were necessary.”

- ^ Bourne pg. 611

- ^ a b Warren pg. 133.

- ^ Warren pg. 134.

- ^ Warren pg. 135

- ^ Warren pg. 34-35

- ^ Bourne pg. 609. Bourne wrote, “The vast length of the exposed frontier made it virtually impossible for the British to defend it in its entirety – but, worse, the Americans were peculiarly well placed to attack it. They not only had superior local resources in men and material, they also had excellent communications for concentrating those resources upon the frontier and for reinforcing them from the heart of commercial and industrial America – in fact sufficiently good communications in Macdougall’s view to outweigh the difficulties of a winter campaign.”

- ^ Bourne pg. 610-613. On the lake situation Bourne wrote, “Quite clearly there could be no hope of securing the command of the lakes unless adequate preparations were made in advance of hostilities. But the time was peculiarly unfavorable for such measures; the whole question of colonial military expenditure had recently been investigated by a committee of the house of commons whose bias was plainly to encourage greater efforts on the part of the colonists themselves. On 17 October, therefore, Somerset had concluded that the defence of all the lakes would be ‘very difficult’ and that the main effort must be left to the Canadians themselves, though ‘perhaps with proper arrangements we might defend Lake Ontario and Kingston Dockyard.’ But even for this limited programme no preparation had been made by the time Lewis raised the matter at the Cabinet of 4 December. Nor was anything done later.”

- ^ Bourne pg 620-621. On December 26 de Gray had prepared a memorandum indicating 7,640 troops would be needed for the initial attack. Macdougall had prepared a memorandum on December 3 in which he suggested that 50,000 troops would be necessary to guarantee success.

- ^ Bourne pg. 625-626. Washington wrote, “Possibly a very strict blockade, without an attack, might induce the people of Maine to consider whether it would not be for their interest to declare themselves independent of the United States, and so profit by all the advantages that would be derived from railway communication with Canada and the Lakes.”

- ^ The Times, 6th January 1862, pg 9 and The Times, 8th January 1862, pg 19

- ^ 10th February 1862, pg10

- ^ The Times, 8th January 1862, pg 10

- ^ Campbell, pg. 64

- ^ Campbell, pg. 60-63

- ^ Moody et al, pg. 775-776

- ^ Baxter, The British Government and Neutral Rights pg 16. Bourne pg. 623-627.)

- ^ Baxter, The British Government and Neutral Rights pg. 17

- ^ Bourne pg. 627 fn 4

- ^ Bourne pg 625

- ^ Bourne pg. 623-624.

- ^ Warren pg. 154

- ^ Weigley pg. 80-81.

- ^ Bourne pg. 630. Bourne wrote (pg. 231), “By the destruction of American shipping, by a severe blockade, by the harassing of the Northern coastal cities and perhaps by the occupation of Maine the British might, while being unable to secure a decisive military victory, not only draw off the enemy from hard-pressed Canada and inspire the South morally and materially, but, above all, so sap the North’s moral and economic strength as to bring her Government to sue for peace on unfavourable terms.”

- ^ Mahin pg. 73.

- ^ Ferris pg. 131-135

- ^ Donald pg. 31-36

- ^ Donald pg. 36-38

- ^ Mahin pg. 70. Ferris pg. 180.

- ^ Ferris pg.80

- ^ Mahin pg. 98. Warren pg. 158. The words in quotes are Dayton’s.

- ^ Weigley pg. 79. Ferris pg. 181-182.

- ^ Ferris pg. 181-183. Taylor pg. 184.

- ^ Taylor pg. 184

- ^ Ferris pg. 184

- ^ Ferris pg. 188-191

- ^ Ferris pg. 192-196.

- ^ Hubbard pg. 64

- ^ Jones pg. 117-137

- ^ Jones pg. 138-180.

- ^ Jones pg. 223.

参考文献[編集]

概論[編集]

- Adams, Jr., Charles Francis (April 1912), “The Trent Affair”, The American Historical Review (American Historical Association) 17 (3), ISSN 0002-8762, OCLC 1830326

- Adams, Ephraim Douglass (1924), “"VII: The Trent"” (txt), Great Britain and the American Civil War, 1, Longmans Green, OCLC 251298695, オリジナルの2007年9月27日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2009年9月21日閲覧。

- Bourne, Kenneth. "British Preparations for War with the North, 1861-1862," The English Historical Review Vol 76 No 301 (Oct 1961) pp 600–632 in JSTOR

- Campbell, W.E. "The Trent Affair of 1861,". The (Canadian) Army Doctrine and Training Bulletin. Vol. 2, No. 4, Winter 1999 pp 56–65

- Moody, John Sheldon, et al. The war of the rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies; Series 3 - Volume 1; United States. War Dept., pp. 775

- Donald, David Herbert, Baker, Jean Harvey, and Holt, Michael F. The Civil War and Reconstruction. (2001) ISBN 0-393-97427-8

- Foreman, Amanda. A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (2011)

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. (2005) ISBN 978-0-684-82490-1

- Fairfax, D. Macneil. Captain Wilkes’s Seizure of Mason and Slidell in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War: North to Antietam edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel. (1885).

- Ferris, Norman B. The Trent Affair: A Diplomatic Crisis. (1977) ISBN 0-87049-169-5

- Graebner, Norman A. "Northern Diplomacy and European Neutrality," in Why the North Won the Civil War edited by David Herbert Donald. (1960) ISBN 0-684-82506-6 (1996 Revision)

- Hubbard, Charles M. The Burden of Confederate Diplomacy. (1998) ISBN 1-57233-092-9

- Jones, Howard. Union in Peril: The Crisis Over British Intervention in the Civil War. (1992) ISBN 0-8032-7597-8

- Mahin, Dean B. One War at A Time: The International Dimensions of the Civil War. (1999) ISBN 1-57488-209-0

- Monaghan, Jay. Abraham Lincoln Deals with Foreign Affairs. (1945). ISBN 0-8032-8231-1 (1997 edition)

- Musicant, Ivan. Divided Waters: The Naval History of the Civil War. (1995) ISBN 0-7858-1210-5

- Nevins, Allan. The war for the Union: The Improvised War 1861-1862. (1959)

- Niven, John. Salmon P. Chase: A Biography. (1995) ISBN 0-19-504653-6

- Taylor, John M. William Henry Seward: Lincoln’s Right Hand. (1991) ISBN 1-57488-119-1

- Walther, Eric H. William Lowndes Yancey: The Coming of the Civil War. (2006) ISBN 978-0-7394-8030-4

- Warren, Gordon H. Fountain of Discontent: The Trent Affair and Freedom of the Seas, (1981) ISBN 0-930350-12-X

- Weigley, Russell F., A Great Civil War. (2000) ISBN 0-253-33738-0

一次史料[編集]

- Baxter, James P. 3rd. "Papers Relating to Belligerent and Neutral Rights, 1861-1865". American Historical Review Vol 34 No 1 (Oct 1928) in JSTOR

- Baxter, James P. 3rd. "The British Government and Neutral Rights, 1861-1865." American Historical Review Vol 34 No 1 (Oct 1928) in JSTOR

- Library of Congress Memory Archive for November 8

- Harper's Weekly news magazine coverage