防諜

この項目「防諜」は途中まで翻訳されたものです。(原文:Counterintelligence at 17:44, 4 June 2014 UTC.) 翻訳作業に協力して下さる方を求めています。ノートページや履歴、翻訳のガイドラインも参照してください。要約欄への翻訳情報の記入をお忘れなく。(2014年9月) |

防諜︵ぼうちょう、英:Counterintelligence、略語CI︶とは、外国政府やテロリストによる諜報活動や破壊活動を無力化することである[1]。

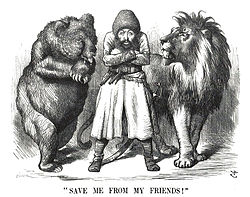

アフガニスタンのシール・アリー・ハーン国王と彼の﹁友人﹂であるロ シアの熊とイギリスのライオンを描いた政治的戯画︵1878年︶。グレート・ゲームでは両国による組織的なスパイ活動と監視がこの地域全体で行われた。

スパイ活動の近代的な戦術と専門的な政府諜報機関の整備は19世紀後半に発展を遂げた。この発展の鍵となった背景には、イギリス帝国とロシア帝国が中央アジアをめぐって繰り広げた戦略的なライバル関係と衝突の時代をあらわすグレート・ゲームにあった。ロシアのこの地域に対する野望とインドにおけるイギリスの立場に対する潜在的な脅威に対抗するため、イギリスはインド高等文官に監視、諜報と防諜のシステムを導入した。この知られざる衝突の存在は、ラドヤード・キップリングの有名なスパイ小説﹃キム﹄のなかで描かれている。彼はグレート・ゲーム︵この言葉は彼によって有名になった︶においてスパイ活動と諜報活動が﹁昼夜を問わず、決して絶えることなく﹂行われる様子を描写した。[4]

専門的な諜報および防諜機関の創設は、ヨーロッパ列強による植民地戦争と軍事技術の開発競争と直接結びついていた。スパイ活動はより広く行われるようになり、外国のスパイを見つけ、取り締まるよう警察と国内の治安を維持する軍隊の役割を広げることは不可欠なこととなった。オーストリア=ハンガリー帝国の諜報局は、19世紀終盤からセルビアの国外で展開されていた汎スラブ主義者による運動に対抗する活動を行う役割を担った。

上述のことがあり、フランスではドレフュス事件が起きた後、1899年に軍事的な防諜の責務を遂行するため、秩序の維持と公共の安全に対して第一義的に責任を負う公安部︵Sûreté générale︶が内務省内に設置された。[5]

オフラーナは1880年に創設され、敵のスパイ活動を取り締まる任務 を担った。1905年、サンクトペテルブルクでの集合写真。

ロシア帝国内務省警察部警備局︵オフラーナ[6]︶は、政治的テロリズムや左翼革命運動に対処するため、1880年に創設されたが、敵国のスパイ活動を取り締まることも任務とされた。[7]その主な関心事は、頻繁に活動する外国から破壊活動の指示を受けた革命家の活動だった。彼らの活動を監視するため、ピョートル・ラフコフスキーはパリにアンテナを建てた。その目的を達成するため、当局は秘密作戦、身分秘匿捜査、私的通信の傍受や解読を含む多くの手段を用いていた。オフラーナはそのプロバカートルを使ったボリシェヴィキを含む革命家集団の活動への浸透工作の成功によって一躍有名になった。[8]

政府の直接の指示による統合された防諜機関もまた創設された。イギリスの秘密勤務局は、政府が防諜活動を指揮する初の独立したおよび省庁間を超える協力の下でできた組織として1909年に創設された。

ウィリアム・メルヴィルによる激しいロビー活動や彼が持っていたドイツの動員計画の情報およびドイツによるボーア人へ経済的な支援が露見したため、政府は陸軍省内に新たに諜報部局を設置する権限を認め、1903年、メルヴィルによる指揮の下、MO3︵その後MO5へと改称︶が組織された。メルヴィルはロンドンの一角に身を潜めて活動し、彼がロンドン警視庁特別部で活動していた頃に築いた知識と人脈を生かし、国内の防諜活動と外国への諜報活動双方に従事した。

その成功により、1909年、政府諜報委員会はリチャード・ホールデンとウィンストン・チャーチルの協力を得ながら、イギリス国内および国外の諜報活動の監督、特にドイツ帝国政府に対する活動に集中するため、海軍本部、陸軍省と外務省が協力して秘密勤務局が設置された。初代長官は通称Cことマンスフィールド・スミス=カミングだった。[9]秘密勤務局は1910年に外国部門と国内の防諜部門とに分割された。後者はヴァーノン・ケルにより指揮され、当初はドイツの大規模なスパイ活動による大衆の恐怖を鎮めることを目的としていた。[10]戦争中、ケルは警察ではない組織の長として、ロンドン警視庁特別部のバシル・トムソンと緊密に連携しながら、インド人革命家たちがドイツ人と協力しながら行っていた活動を中止させたりした。ライバルの省庁や軍の組織への相談や協力を仰ぐことなく優先的に活動することができるようにするため、新たに設置された秘密情報部は省庁を超える協力の下でできた組織であり、関連する他のすべての政府機関より優先的にその機密資料に接することができるようになった。[11]

政府は、より場当たり的だった以前とは対照的に、初めて平時において、整理され、手続きが定義されているのと同時に中央集権化され独立した、諜報と防諜の官僚組織を持つことができるようになった。

概要[編集]

防諜とは、外国政府やテロリストによる諜報や破壊活動を無力化し、それらから政府機関の情報プログラムを守ることを目的とする活動である[2]。外国勢力やその組織または個人、国際テロ活動などによって代表、あるいはそれらのために実行される防諜やその他の諜報活動・妨害工作・暗殺などに対抗して収集された情報や活動を指し、人的、物的、文書あるいは通信セキュリティプログラムを含むことがある[3]。歴史[編集]

防諜手段[編集]

防諜手段としては以下のものが挙げられる。 ●防諜捜査︵CI investigation︶‥公安警察による法に基づく捜査活動。 ●防諜作戦︵― operation︶‥支援作戦と機密作戦に分類される。 ●支援作戦︵― support operation︶‥情報保全の支援。 ●機密作戦︵― sensitive operation︶‥外国政府の諜報活動に対する攻勢作戦。対スパイ︵counter-espionage、略語CE︶作戦を含む。 ●防諜収集︵― collection︶ ●収集活動︵Collection activity︶‥外国政府の諜報活動に関する情報収集。 ●連絡︵Liaison︶‥情報交換のための友好国の情報機関との接触。 ●情報源の収集活動︵CASO: Collection Activities and Source Operations︶‥直接の脅威に関する情報収集。 ●選別︵Screening︶‥主としてHUMINTを利用した人物の資格審査。人物の採用の際に実施される。 ●聴取︵Debriefing︶‥民間人からの事情聴取。 ●機能サービス︵Functional Services︶‥ ●脅威評価︵TVA‥threat vulnerability assessment︶‥ ●敵諜報模擬︵Adversary intelligence simulation︶‥レッド・チーム評価︵Red Team Evaluation︶ ●秘匿エージェント支援︵Covering agent support︶ ●技術サービス︵― Technical Services︶ ●視察︵Surveillance︶ ●嘘発見器︵Intelligence polygraph︶ ●TSCM ●コンピュータ・ネットワーク作戦︵CNO:Computer Network Operation︶ ●情報作戦︵IO︶ ●対信号諜報︵C-SIGINT:Counter-Signals Intelligence︶ ●分析︵Analysis︶‥外国政府の諜報活動を分析。 ●生産︵Production︶‥情報評価、報告書の作成。 ●技術サービス︵Technical services︶‥防諜機関の技術的支援。[12]防諜機関[編集]

多くの国の政府は情報機関と防諜機関を分けて組織しており、防諜機関はアメリカの連邦捜査局︵FBI︶や日本の公安警察のように、警察内の一部門として組織されている場合が多い。また、イギリスの防諜機関である内務省公安部︵MI5︶は直接的な捜査権を持っていないが、捜査権のあるロンドン警視庁公安部︵Special Branch︶と呼ばれる公安警察と緊密に協力している。 ロシアの主な防諜機関は、ソビエト連邦期の国家保安委員会︵KGB︶の第2本部および第3本部が前身である連邦公安庁︵FSB︶である。 カナダは王立カナダ騎馬警察の公安警察が諜報活動と防諜活動を一手に担当していたが、1984年にカナダ公安情報部︵CSIS︶が発足して諜報活動を担うようになり、諜報と防諜が分離した。 フランスでは、国内におけるテロ対策を警察機関の枠組みのなかに作りあげている。テロ対策担当の予審判事は、アメリカとイギリスにおける捜査官、検察官、裁判官の機能を併せ持つ複数の機能を担っている。テロ対策担当予審判事は、防諜機関の国土監視局︵DST︶や情報機関の対外治安総局︵DGSE︶から協力を要請され、ともに活動することもある。 スペインでは、内務省が軍の支援を受けながら国内におけるテロ対策を担当している。外国からの防諜活動は、国家情報本部︵CNI︶が責任を負っている。2004年3月11日のマドリード列車爆破テロ事件の発生後、内務省と国家情報本部との連携で問題があったことが発覚し、国家テロ対策本部が創設された。スペインのテロ事件調査委員会は、この本部を作戦の調整のためだけでなく、情報収集のためにも活用することを提言している。[13] 防諜活動の内容も攻撃的なものと防御的なものに分類される場合もある。アメリカの中央情報局︵CIA︶の国家秘密本部︵NCS︶は攻撃的カウンターインテリジェンスを担当するのに対し、国務省の外交保全局︵DSS︶は、アメリカの在外公館︵大使館・総領事館︶において、人と情報の保護に携わる防御的カウンターインテリジェンスを担当する。[14] 防諜活動という用語は、現実的には諜報活動に対抗するものを指すとされるが、攻撃的カウンターインテリジェンスには諜報活動が含まれるため、ここでは広義の意味で捉えられることを避けるために使われている。主な防諜機関[編集]

詳細は「en:List of counterintelligence organizations」および「情報機関の一覧」を参照

- 日本

- 米国

- 連邦捜査局(FBI)国家公安部

- 英国

- 内務省公安部(MI5、正式にはSS)

- ロシア

- ロシア連邦保安庁(FSB)

- イスラエル

- イスラエル公安庁 シャバック(שב"כ)

- フランス

- フランス国土監視局(DST)

- ドイツ

- 連邦憲法擁護庁(Bfv)

防諜の任務[編集]

CIAの工作本部長を務めたフランク・ワイズナーは、直属の上司であったアレン・W・ダレスCIA長官の言葉を引用し、防諜とは﹁敵対するものによって提起された状況に対抗するためだけに、動くものである﹂と語り[15]、防諜が﹁敵対する諜報活動に携わる者﹂に対する精力的な攻撃を行うときに、最も効果的なものになりうると考えていた[16]。

現代の防諜活動は、脅威が外国政府の諜報活動に限定されていた時代と比べ、拡大されてきている。最大の脅威は、非国家かつ多国籍のテロリストである。それでもなお、外国政府の諜報活動は防諜に対する脅威であり続けている。

防諜は、インテリジェンス・サイクル・セキュリティの部分を構成するものであり、同様に、インテリジェンス・サイクル・マネジメントの一部を構成するものでもある。以下に示すような、

(一)物理的セキュリティ︵Physical security︶

(二)人的セキュリティ︵Personnel security︶

(三)通信セキュリティ︵Communications security、COMSEC︶

(四)情報セキュリティ︵Information security、INFOSEC︶

(五)セキュリティの機密化︵Security classification︶

(六)運用におけるセキュリティ︵Operations security、OPSEC︶

にみられるセキュリティの分野の多様性もまた、インテリジェンス・セキュリティ・マネジメントと防諜の学問分野に含まれる。﹁積極的セキュリティ﹂という言葉に含まれる訓練や、社会の実際の、また潜在的なセキュリティに関する情報を集めるための手段もセキュリティに含まれる。例えば、諜報機関が通信を傍受して特定の国で使われているただひとつの特定の無線送信機を識別したとき、その人物が使用した無線送信機を検知したということは、防諜の対象となるスパイの存在を示唆していることになる。特に、防諜は、少なくとも他のものと比べ、ヒューミントのディシプリンに関する情報収集と大きな関係を持っている。防諜は情報の生産と保護の両方を行うことができる。

アメリカの諜報と関連のある省庁は、幹部の業務︵Chief of Mission︶の権限によるものを除き、海外における防諜について、自身が責任を負う[17]。

政府は自国の人員、設備、情報を保護する目的で防諜する。多くの国の政府は、これらの保護の責任を分散させている。アメリカのCIAの防諜体制は、人員と設備の保護は警備部︵Office of Security︶が、情報の保護は国家秘密本部︵NCS︶内の防諜部と各地域部が連携して担当している。防諜の第一人者といわれるジェームズ・ジーザス・アングルトンが防諜部長を務めていた時は、防諜部は完全に独立して業務を遂行していた。アメリカ軍の防諜体制についても同様に、複雑に分割されてきた。

防諜機関は緊密な連携が求められる。アメリカの防諜機関の相互依存についてはアメリカ人の社交性と関連があるとされている。一方で、相互依存によるリスクも存在する。[17]

防諜で重要なのは、獲得工作を防ぐことである。実際、冷戦時代にKGBが獲得工作に重点を置いていたことが研究から明らかとなっている。

イギリスでは、ケンブリッジ・ファイヴの発覚により、ソ連の獲得工作が明るみに出た。さらに、内務省公安部︵MI5︶長官であったサー・ロジャー・ホリスにもソ連の協力者ではないかという疑惑が起こるなど、ソ連による獲得工作はイギリス政府の首脳部にまで達していた。

アメリカでも、KGB将校であるアナトリー・ゴリツィンとユーリ・ノセンコの亡命による告発をめぐり大きな混乱が起きた。ゴリツィンはアングルトンが大きな信頼を寄せていたキム・フィルビーについて密告した。CIA工作本部のジョージ・キセバルターは、アメリカとイギリスが共同で行っていたオレグ・ペンコフスキーの獲得工作について、KGBが仕掛けた罠であるというアングルトンの説を信じなかった。ノセンコは、KGBのイギリス海軍に対する諜報活動の中心人物であったジョン・バッサルについて暴露したが、バッサルはKGBが他の諜報活動について秘密を保護するための生贄であるという主張も存在していた。

防御的カウンターインテリジェンス[編集]

防御的カウンターインテリジェンスは、その組織自体の脆弱性を探すための実践的な訓練であり、そして、リスクと利益に注意を払いながら、弱点の発見に近づいていく。 防御的CIは、外国の諜報活動︵FIS︶によって発見されやすい、組織の中で脆弱な場所を探すことから始まる。FISはカウンターインテリジェンス・コミュニティによる造語であり、そして、今日の世界では、﹁外国﹂とはすなわち﹁対立するもの﹂と置き換えられる。対立するものは実際に国家であるかもしれないが、国境を超える集団または国内の反乱者の集団であることもある。FISに対抗する作戦は、自国や友好国の安全を脅かす集団に対抗するためのものである可能性もある。友好国の政府を支援するためになされる活動の範囲は、幅広い機能を含むこともあり、軍事支援や防諜活動だけでなく、人道支援や開発援助︵例えば国家の建設︶もその範囲に含まれる。[18] ここで使われている用語は、まだ定義が定まっていないものもあるが、﹁国境を超える集団﹂にはテロリスト集団だけでなく、国境を超える犯罪組織も含まれる。国境を越える犯罪組織には麻薬取引、資金洗浄、サイバーテロ、密輸を行う集団などが含まれる。 ﹁反乱者﹂とは、その国の政府によって犯罪組織または軍事組織と認識されている政府に対立する集団である場合や、自国や友好国の政府に対する秘密の諜報活動や秘密作戦を行っている疑いのある集団であることもある。 カウンターインテリジェンスとカウンターテロリズムは、外国の諜報機関やテロリスト集団に対する戦略的な評価や、現在進行中の作戦や捜査への戦術的なオプションの準備を提供すると分析されている。カウンターエスピオナージには、二重スパイ、欺騙、または外国の諜報機関の職員をリクルートすることなどの外国の諜報活動に対する積極的な行動も含まれる。秘密のヒューミントの人的資源は、敵の思考に対して最大の洞察を与えるが、それらはまた、敵の攻撃においてその組織の最も脆弱なものとなりうる。敵のエージェントを信用する前に、そのような人物が自国で信用されているかどうかを疑ってから始めることを忘れてはならない。彼らはその国に未だに忠誠を誓っているかもしれないからである。攻撃的カウンターインテリジェンス[編集]

攻撃的カウンターインテリジェンスは、発見した外国の諜報活動を行う人物を無力化し、逮捕するか、あるいはその人物が外交官である場合には、ペルソナ・ノン・グラータを宣言することによって国外退去を命じる、必要最低限の、一連の技法である。その最低限のことを行った後、諜報活動を行う人物に関する情報を獲得しようとするか、または敵意のある諜報機関に対してダメージを与えるために活発な情報操作を行う。 ワイズナーは彼自身およびダレスとともに、外国からの攻撃、勢力の浸透、または諜報活動に対する最善の防御の方法は、それらの敵意のある活動に対して積極的な方法をとることであると強調した。[16]これはしばしばカウンターエスピオナージと呼ばれる方法であり、敵による諜報活動または友好国に対する諜報活動への物理的な攻撃を検知し、損害を与えることや情報の損失を防ぎ、可能であるならば反撃を行うことである。カウンターエスピオナージは敵に対抗するために行われるものだけでなく、外国の諜報機関のエージェントをリクルートすることや、実際に自身の活動に忠誠を誓っている人物を疑うこと、敵の諜報活動にとって有益なリソースを取り除くことにより、敵の諜報活動を撃退しようと積極的に試みるものである。これらのすべての行為は、国家による組織だけでなく非国家的な脅威にも適用される。 もし自国で、あるいは友好国で敵意のある行為が行われた場合には、警察による協力を通じて、敵のエージェントは逮捕されるか、あるいはその人物が外交官である場合には、ペルソナ・ノン・グラータが宣言される。諜報活動の観点からは、逮捕または脅威を取り除くための行為のために、ある側にとって有利となる状況を利用することは、通常好ましいことである。諜報活動の優先権は、特に外国の脅威と自国民とともに活動する外国人が重なる場合、時として法執行機関の本来の役割と抵触することがある。 囚人に協力する選択する手段が与えられている場合、または深刻な状況に直面している場合、そしてスパイ活動によって死刑が言い渡されている場合を含むいくつかの状況では、最初の手順として逮捕という措置が取られる。この協力とは、その組織について誰もが知っていることを供述することであるが、できれば敵対組織に対する欺瞞的行動を積極的に支援することである。防諜による諜報活動の安全の確保[編集]

防御的カウンターインテリジェンスでは、特に諜報活動を行う際の、文化、源泉、手段と資源におけるリスクの分析が行われる。効果的な諜報活動はしばしばリスクを負って行われるものであるため、リスク管理はそれらの分析に常に反映されなければならない。リスクを計算に入れている場合でさえ、適切な対応策を取り入れることによって活動のリスクを軽減する必要がある。 FISは特に開かれた社会、また、その環境において開拓していくことができ、インテリジェンス・コミュニティーを崩壊させるために内部の人物と接触してきた。攻撃的カウンターエスピオナージは侵入者を見つけ、無力化するための最も強力な手法であるが、それが唯一の手段ではない。何が個人を所属している側から転向させるのかについて理解することが囚人プロジェクトの目的である。個人のプライバシーを侵害することなく、特に情報システムの利用における、異常な振る舞いを見つけるためのシステムを開発することは可能である。 ﹁意思決定者は敵の諜報機関による管理または操作から自由であることが求められる。なぜならすべての諜報機関のディシプリンは我々と対峙する勢力を操作することを目的としているからであり、すべての情報の収集の目的と原則から諜報活動の信頼性を有効なものにすることは必要不可欠である。従って、各々の諜報機関は、防諜の任務に関連する源泉と方法の信頼性を普遍的な標準に従って有効化しなければならない。他の任務の分野では、我々は情報を収集、分析して実践と他の諜報活動に普及させ、改善、最善の方法、普遍的な標準を推進する﹂。[19] 諜報活動は国外だけでなく国内の脅威からも攻撃を受けやすい。それは転覆、背信、脆弱性、政府と企業の秘密、そして諜報活動の情報源と方法のリークなどによってである。この内部の脅威は、オルドリッチ・エイムズ、ロバート・ハンセン、エドワード・リー・ハワードなどの主な秘密活動にアクセスすることができた人物により、アメリカの国家の安全保障に甚大な被害を与えてきた。防諜に関するファイルを閲覧する際の異常な行動を検知する電子システムを導入していれば、ロバート・ハンセンのソビエト︵後のロシア︶から報酬を受け取っていたことへの容疑による捜査はもっと早く表面化していたかもしれなかった。異常は、単純に特に独創的な分析官が訓練された直観によって関係があると感じ、それらについて調査しようとすることによって現れる。 これらの新たなツールと技術が﹁国家の造兵廠﹂に加わったことにより、カウンターインテリジェンス・コミュニティは外国のスパイの操作、積極的な捜査の指揮、逮捕または、外交官が関わる場合には、彼らが実際の外交上の地位と矛盾したことを行ったように関連付けて国外に追放するか、または欺くために彼らを無意識のうちに経路として利用するか、または彼らを二重スパイに仕立てようとする。[19]﹁気づいている︵Witting︶﹂とは諜報活動の神髄を示した用語であり、事実または情報の断片への気づきだけでなく、その諜報活動に対する関連性への気づきをも示している。 ヴィクトル・スヴォーロフは、かつてのソビエト軍の諜報機関︵つまりソビエト連邦軍参謀本部情報総局︵GRU︶の偽名の工作員であるが、彼はヒューミントの工作員が亡命することは、亡命のために離反を始めようとする工作員または志願して国を後にしようとする者にとって特別な脅威となると主張した。﹁温かく迎えられた﹂志願者は、彼らが敵の諜報員から軽蔑されているという事実を考慮していない。 ﹁共産主義の醜い側面を非常に多く見てきたソビエトの諜報員は、同胞を喜んで売り渡す者に対して最大限の反感を持つことが非常に多い。そしてGRUまたはKGBの職員が、彼が所属している犯罪的な組織との関係を断とうと決断したとき、何かの幸運がよく起こり、彼が真っ先に行うのは、その嫌悪すべき志願者について暴露しようとすることである﹂。[20]防諜部隊防護活動[編集]

軍事、外交およびその関連施設に対する攻撃は、1983年にベイルートで行われたフランスとアメリカの平和維持軍に対する攻撃や、1996年のサウジアラビアのアル・コバール・タワーに対する攻撃、1998年のコロンビアとケニアで行われた基地や大使館に対する攻撃、2000年にケニアで行われたアメリカ海軍のミサイル駆逐艦に対する攻撃など、実際に起こりうる本当の脅威である。アメリカ軍を保護する方法は、軍人やその家族、資源、施設と機密情報に対して行われる一連の活動に向けられるものであり、そしてほとんどの国はそれらの施設を保護するために同じようなドクトリンを持っており、また起こりうる攻撃に対して注意深く備えている。部隊防護は偶然または自然災害によらない、故意の攻撃からの防護と定義される。 防諜部隊防護活動︵CFSO︶は海外において人的資源を活用して行われる作戦であり、通常は秘密裏に行われ、国内とのセキュリティのレベルのギャップを埋めるとともに、諜報活動を行う際に指揮官からの諜報員への要求を満たすことが目的である。[21] 地元の人々と交流している軍警察やパトロール隊は、防諜のためのヒューミントの資源としては本当に価値があるかもしれないが、彼ら自身が防諜部隊防護活動を行うことはない。グレッグホーンは国家の諜報機関の諜報員の保護と、敵を撃退するための軍隊を提供したり、部隊防護のための情報の提供が諜報機関に必要とされることを区別している。ヒューミントの資源は、本当にヒューミントとして利用するかもしれないが、特に防諜と関連があるわけではい外国人との混同を防ぐ軍の偵察パトロール隊など他にもある[22]。部隊防護、諜報機関の活動、または国家の安全保障にとって重要な施設の保護に用いられるアクティブ・カウンターメジャーは、ヒューミントのディシプリンと関わりがあるが、外国のエージェントを発見するための非正規、臨時のあるいは付随した資源と呼ばれる人的資源からの情報、例えば、 (一)政治亡命のために離反を始めようとする情報機関に志願して採用された者 (二)気づいていない人的資源︵防諜にとって有益な情報を提供し、漏洩の過程にあるそのような情報が、審査で彼らに有利に働いているとは知らないかもしれない、すべての個人︶ (三)発見され捕虜となった者 (四)難民と国外追放者 (五)審査中に接触を受け、面接を受けた者 (六)公式の連絡係 から受け取った情報の選別と報告を行う。 ﹃物理的セキュリティは重要である、しかしそれが部隊防護活動の役割に優先することはない...すべての諜報機関のディシプリンは部隊防護活動のための情報を収集するために利用され、諜報活動と諜報機関によって収集されたヒューミントの情報は、テロリストや部隊防護の他の脅威の示唆と警告を与える際に重要な役割を果たす﹄。[23] 現地国に展開する軍への部隊防護は、任務の遂行中や、宿泊先においてさえ、国家レベルのテロ防護組織による十分な支援を受けていないかもしれない。ある国において、すべての活動の、軍事支援や顧問団とともに、部隊防護防諜活動の人員とともに活動することにより、現地国の法執行機関と諜報機関との関係を築き、地域の環境について理解し、言語能力を改善することが可能になる。部隊防護防諜活動による国内のテロリズムの脅威への取り組みのためには、その国における法的な能力の問題を解決することが必要となる。 コバール・タワーへのテロ攻撃におけるテロリストの計画が教訓となり、長期間にわたる部隊防護防諜活動の必要性が明らかとなった。﹃ヒズボラのスパイたちは、この攻撃のための情報の収集と計画の活動が1993年に開始したと考えられていた。彼らは1994年の秋にアメリカ軍の軍人がコバール・タワーに宿泊していたことを認識し、施設の下見を開始し、テロの計画を立てるため1995年の6月まで継続した。1996年3月、サウジアラビアの国境警備隊がプラスチック爆弾を持ち込もうとしたヒズボラのメンバーを逮捕し、2人のヒズボラのメンバーのさらなる逮捕につながった。ヒズボラの指導者はそれらの逮捕により、代わりの人材をリクルートし、テロの計画を継続した﹄[24]。防御的カウンターインテリジェンスの任務[編集]

アメリカのドクトリンでは、他の国のそれでは必ずしも必要不可欠なものではないが、CIは外国の諜報活動によるヒューミントに対抗するための基本的な手段である。1995年のアメリカ陸軍のカウンターインテリジェンスのマニュアルでは、CIは様々な情報収集のディシプリンに幅広く焦点を当てている。CIのタスクの全体の一部を紹介すると、 (一)CIの関心事となる組織、場所、そして個人について発展、維持、そして複数のディシプリンに基づいた脅威となるデータとインテリジェンスに関する情報の収集を進めること。これには、反乱者やテロリストの下部組織やCIの任務を支援することができる個人が含まれる。 (二)すべての分野のセキュリティに携わる人員に対して教育を施すこと。この内容は脅威に関する複数のディシプリンについてのブリーフィングである。ブリーフィングの焦点と機密種別のレベルは調整することができるし、されなければならない。その際、ブリーフィングを用いてサポートされている指令に、その指令または活動に対して発生する多分野の脅威の性質を徹底させることができる。 より最近のアメリカ軍が使用しているインテリジェンスのドクトリン[25]は、その基本的な対象を、通常カウンターテロリズムを含む、カウンター・ヒューミントにだけ向けるよう厳しく制限されている。軍事または他のリソースに対する脅威に関するすべての情報収集活動について、誰が責任を負うのか、このドクトリンのもとでは必ずしも明確ではない。アメリカ軍のカウンターインテリジェンスのドクトリンの総覧については、統合作戦を支援するためのカウンターインテリジェンスとヒューマンインテリジェンス︵Joint Publication (JP) 2-01.2, Counterintelligence and Human Intelligence Support to Joint Operations︶として資料が公開されている。 情報収集活動のディシプリンに対するより特定の対抗手段は以下の通りである。| ディシプリン | 攻撃的CI | 防御的CI |

|---|---|---|

| ヒューミント | 対偵察、攻撃的カウンターエスピオナージ | 作戦の安全を確保するための欺騙 |

| シギント | 運動エネルギーおよび電子攻撃の推奨 | 安全な電話、暗号、欺騙を用いた無線の運用セキュリティ |

| イミント | 運動エネルギーおよび電子攻撃の推奨 | 欺騙、運用セキュリティの対抗手段、欺騙(おとり、カモフラージュ)、可能であるならば、隠れたり活動を中止して上空の衛星からのレポートを利用する |

カウンター・ヒューミント[編集]

カウンター・ヒューミントは組織内において、敵のスパイまたは二重スパイとして活動するヒューミントの源泉の発見、または敵のヒューミントの源泉となりそうな個人の発見の双方を扱う。カウンターインテリジェンスの幅広いスペクトラムに関連するもうひとつのカテゴリーがある。なぜ個人がテロリストとなるのかということである。

MICEとは、

●Money︵金︶

●Ideology︵イデオロギー︶

●Compromise (or coercion)︵ハニートラップのような罠に嵌めることによって弱みを握り、意のままに動くことを強いること(?)︶

●Ego︵欲求︶

の頭字語であり、人々が裏切りや機密資料の公開、敵への作戦の漏洩、またはテロリスト集団に加わるような行為を行う最も普遍的な理由を表している。それゆえ、これらの領域におけるリスクのために信頼のある人物が経済的なストレスを抱えているかどうかや極端な政治思想に傾倒していないかどうか、恐喝に対して脆弱であるかどうか、周囲から認められるために過度な欲求を持っているかまたは批判に対して不寛容であるかについて監視することは有意義である。もし幸運であれば、問題を抱えている職員をいち早く見つけ、彼らを思いとどまらせるための支援が提供され、スパイ行為を回避するだけでなく、有用な職員として活用することができる。

時には、アール・エドウィン・ピッツの事例のように、予防と中立化の任務が重なることもある。ピッツは機密情報をソビエト、ソビエト連邦の崩壊後にはロシアに売り渡したFBIのエージェントであった。ピッツはロシアのFSBのエージェントのふりをしたFBIのエージェントとしてふるまうよう打診され、彼はFBIに対する背任の容疑によって逮捕された。彼の活動は、彼がFBIのエージェントであった頃に感じた悪い扱いを背景とした、金と欲求の双方が動機であると思われた。彼に言い渡された刑罰により、彼は知っている外国のエージェントについてFBIにすべて話すよう要求された。皮肉なことに、彼が話したロバート・ハンセンによって容疑をかけられた行為は、その時点では深刻に受け止められていなかった。

情報や作戦を漏洩しようとする動機[編集]

そのスローガンが宣言された後、囚人プロジェクトは中央情報局長官の指揮の下で行われたインテリジェンス・コミュニティーの職員の努力の成果であり、囚人プロジェクトの特徴を見つけるため、インテリジェンス・コミュニティーの支援によって行われたスパイ活動の研究である。それは﹁実際のスパイ活動の目的について、面接と心理学的な評価によるスパイ活動についての分析であり、さらに目的の知識について情報を提供しうると考えられる人物は、より深く目的を理解するため接触され、私生活と彼らがスパイ活動に従事している時に他の人からどのように受け止められているか観察される﹂。[26]| 態度 | 兆候 |

|---|---|

| 彼の基本的な思考の構造 |

|

| 彼は自分の行為によって孤立していると感じている。 |

|

| スパイ活動への着手 |

|

囚人プロジェクトとカウンターエスピオナージに対する議会の監視について、ある記者の報告によると、公正で基本的な機能のひとつは、外国のヒューミントとなる可能性があるか、または既に転向した可能性がある職員の振る舞いを監視することである。報道を振り返ってみると、警告は発せられていたが気付かれていなかったことを示している[27]。オルドリッチ・エイムズ、ジョン・アンソニー・ウォーカーやロバート・ハンセンなどの数人の著名な人物によるアメリカへの浸透の事例は、報酬に満足していない個人によるものというパターンを明らかにした。相続や宝くじの当選など完全に善意の理由で金遣いを変える人々もいるかもしれないが、そのようなパターンは無視されるべきではない。

他の人とうまくやっていくことが難しい敏感な状況に置かれている人物は、欲求に基づいたアプローチと妥協するリスクとなるかもしれない。CIAの監視部門の低い地位の職に就いていたウィリアム・カンパイルズはKH-11の重要な作戦マニュアルをわずかな報酬と引き換えに売却した。面接官に対し、カンパイルズは日常的に上司や同僚と衝突を起こしており、もし誰かが彼の﹁問題﹂に気づいていたら、また外部のカウンセリングを受けていたら、彼はKH-11のマニュアルを盗まなかったかもしれないと述べた。[27]

1997年までに、囚人プロジェクトの報告書は、セキュリティ・ポリシー諮問委員会の公式会合に提出されていた[28]。1990年代中盤の予算の削減が原動力の損失につながった一方で、調査結果はセキュリティ・コミュニティの間で利用された。彼らは

﹁スパイ活動の根底には根源的かつ複眼的な動機のパターンが横たわっている。将来の囚人分析はスパイ活動における金が果たす役割、忠誠心の新しい側面のような新たな問題の追究と何が産業スパイ活動の進展に向かわせるのかについて焦点が当てられるだろう﹂

と強調した。

カウンター・シギント[編集]

軍事やセキュリティを取り扱う組織は、商業的な電話または一般的なインターネット接続において情報が通過する際に不適切な情報を検知することによって、安全な通信、そして監視のない安全なシステムを提供する。専門的な技術に詳しい者による傍受に対して脆弱なものにならないようにするため、安全な通信を利用するための必要な教育、そしてそれらを正しく利用するための指導が行われる。カウンター・イミント[編集]

イミントに対抗する基本的な手段は、いつ敵が写真を撮影し、写真の撮影を妨害するのかを知ることである。ある状況、特に自由な社会においては、公的な建造物が常に写真やそれ以外の技術の標的となることは受け入れなければならない。 カウンターメジャーには目視可能な敏感な対象物を秘匿またはカモフラージュすることも含まれる。偵察衛星のような脅威に対処するには、衛星が上空にいるときに、その周回軌道に気づくことによって人員に活動を止めさせて安全を確保することができる、あるいは機微に触れるような部分を隠すことができるかもしれない。これはまた、偵察用の航空機や無人機にも適用され、より直接的にそれらを撃墜する、あるいはそれらの出撃の際やまたは支援の範囲内にある間に攻撃するという手段もあるが、戦時においては選択肢の一つとなる。カウンター・オシント[編集]

オシントの分野の概念が広く認識されるまでは、国家の安全保障に直接関わる資料は検閲を行うことがオシントに対処するための基本的な考え方だった。民主的な社会では、戦時においてすら、検閲は報道の自由を侵すことがないように注意しなくてはならないが、そのバランスの設定は国と時代によって異なる。 イギリスは一般的に報道の自由が非常に高い水準で保障されていると考えられているが、かつてはD-Noticeと呼ばれ、現在はDA-Noticeと呼ばれている制度が存在する。多くのイギリス人ジャーナリストはこの制度が常に議論の対象となるだろうと思いながらも公正に運用されていると考えている。MI5の元高官でありながら年金を受け取ることなく、彼の著作である﹃スパイキャッチャー﹄を出版する前にオーストラリアに移住したピーター・ライトは、特定の状況における防諜活動について言及した。その書籍の多くにおいて合理的な著述をするなかで、それは無線の受信機の存在と設置した場所を検知する手段であるラフター作戦のようないくつかの特定の及び機微に触れるような技術について明らかにしている。カウンター・マシント[編集]

マシントはここでは完結したものとして言及する。しかしその分野にはとても幅広く、領域のタイプごとに異なる戦略的な技術が含まれるが、それはここでの焦点ではない。しかしながら、ひとつの例を取りあげるとするならば、ライトの書籍によって明らかにされたラフター作戦の技術があげられる。マシントで取り扱う無線の周波数には中間域の周波数が使われているという知識により、ラフターの監視技術では検知することができない信号によって交信を行う受信機を設計することが可能となる。攻撃的カウンターインテリジェンスの理論[編集]

現在のカウンターインテリジェンスにおける攻撃ドクトリンは、基本的には人的資源に対して直接狙いを定めるものであり、それゆえカウンターエスピオナージは攻撃的カウンターインテリジェンスの一部と考えることができる。作戦を展開する上での核心は、敵の諜報機関またはテロリスト組織の活動の有効性を落とさしめることである。攻撃的カウンターエスピオナージ︵とカウンターテロリズム︶は2つの方法で行われ、どちらもいくつかの方法によって敵︵外国の諜報機関またはテロリスト︶を操作するまたは敵の通常の作戦を混乱させることによって行われる。 防御的カウンターインテリジェンスの作戦は、容疑者を逮捕することにより、秘密のネットワークを突き破るか、または外国の諜報機関に対してそれが全く捕捉可能であり、もし防諜活動が正しく行われるならばそれが効果的であることを彼らの活動を示威することによって進められる。もし防御的カウンターインテリジェンスによってテロリストの攻撃を阻止することができているならば、それはうまくいっているといえる。 攻撃的カウンターインテリジェンスは、長期的な観点から敵の能力にダメージを与えようとする。もしそれによって自国に敵対する勢力が存在しない脅威に対して大規模なリソースを投入することにつながる、またはテロリストがその国における彼らの﹃スリーパー・エージェント﹄がすべて信頼できるものではなく、代わりの人材に置き換えなければ︵そしてセキュリティ上のリスクを潰さ︶なければならないと考えるようになれば、単独の防衛の作戦上の見地からはそれ以上はない大成功といえる。しかしながら、攻撃的カウンターインテリジェンスを実施するためには、検知以上のことをしなければならない。敵と関係のある人物を騙さなければならない。 カナダ国防省はその軍警察国家防諜隊の指令においていくつかの論理的に意義のある分類をしている[29]。その用語法は他で使われているものと同じではないが、その分類は有益である。 (一)﹃カウンター・インテリジェンスとは敵意のある諜報機関、またはスパイ活動、破壊活動、国家転覆、テロリストの活動、組織化された犯罪や他の犯罪行為と関係があるおそれがある個人によって提起された国防省の職員、カナダ軍の隊員、そして国防省とカナダ軍の所有物と情報の安全に対する脅威となる懸念の特定とそれへの対応の活動を意味する﹄。これは他でいう防御的カウンターインテリジェンスに相当する。 (二)﹃セキュリティ・インテリジェンスとは敵意のある諜報機関やスパイ活動、破壊活動、国家転覆、テロリストの活動、組織化された犯罪や他の犯罪行為と関係があるおそれがある個人の身元や属性、能力の特定、意図を探ること意味する﹄。これは攻撃的カウンターインテリジェンスに直接あたるものではない︵強調が付け加えられている︶が、攻撃的カウンターインテリジェンスを実施するための諜報活動の準備の必要性を示している。 (三)カナダ軍国家防諜隊の任務には、﹃国防省とカナダ軍に対するスパイ活動、破壊活動、転覆、テロリストによる活動や他の犯罪行為の脅威となる存在の素性の特定、捜査と対処、高度の機密情報または特別な国防省またはカナダ軍の所有物を危険にさらすおそれのある現実のまたは起こりうる脅威の身元や属性の特定、捜査と対処、防諜の捜査、作戦の実施と国防省とカナダ軍の権益を脅威から守るため、または予防するためのセキュリティに関するブリーフィングとデブリーフィング﹄が含まれる。この指令は攻撃的カウンターインテリジェンスを実施するうえではよい文章の指令である。 国防省は、﹃セキュリティ・インテリジェンスのプロセスは刑事事件の犯罪者情報の獲得が目的であり、この種の情報の収集がその任務の範囲内に止まるカナダ軍国家捜査局による捜査と混同してはならない﹄とさらに有益な定義づけをしている[30]。 防諜の訓練を受けた本職の諜報員を操ることは、彼の気が向いていない限り容易ではない。思いやりのある人物から始めない試みは、長期間の従事と、自らが防諜の標的であることや防諜のテクニックも理解している誰かの防御を打開するための創造的な思考力を要するだろう。 一方、テロリストはセキュリティの機能として偽装工作に関与するが、外国の諜報機関よりもうまく配置された敵に操られたり騙されたりする傾向があるようだ。これは部分的には多くのテロリスト集団のメンバーが﹁しばしばお互いを信用せず、争いあい、意見が異なり、様々な信念を持っている﹂という事実によるものであり、外国の諜報機関として内部的に団結しているわけではなく、彼らが欺騙と操作によってより脆弱になる可能性を表している。 特に本職として始めたわけではない、攻撃的カウンターインテリジェンスの役割を果たそうとする人物は、様々な方法で存在する。研ぎ澄まされた感覚を磨くよう注意深く養成された人物は、Aという機関に対して敵対的な行為を行おうとするか、あるいは日和見的になり、離反してしまうかもしれない。 離反のように日和見的に獲得された者は、事前に予想されておらず、そのため計画もされていないという不利な点がある。二重スパイになるという決断は大いなる熟考、分析、評価の末に行われ、もしその人物が志願した場合、それを受け入れる組織は影響について考える十分な時間がないまま行動せざるをえない。このような状況では、殊にその人物が秘密裏に接近してきた場合には、志願者について精査する必要性と危険を回避する必要性とが抵触する。志願者と離反者は油断のならない相手であり、扇動の可能性は常に存在する。他方で最善の作戦は志願者によってもたらされることもある。諜報機関のプロフェッショナルとしてのスキルはこのような状況を処理する能力によって試される。[31] エージェントとしての志願者が現れたとき、作戦が意味があるものであるかどうか、志願者が作戦にふさわしい人物かどうか、組織がその作戦を支援することができるかどうかを判断するためには4つの基本的な質問が必要になる。| 問い | 答え |

|---|---|

| 彼はすべてを語っているか? | 通常は、候補者に対するポリグラフ検査、幹部による審査、そして書類選考などを行うことによって十分な情報を得ることができる。これらの手続きは採用されない者には行われないため、意思決定は非常に迅速に行われなければならない。特に危険な隠蔽の可能性があるふたつの点は、かつての諜報機関との繋がりとside-commoである。 |

| 彼には耐性があるか? | この用語は2つの概念、彼が近い将来に防諜の対象となる人物にアクセスし続ける能力、および彼が二重スパイを演じる際に生じる恒常的な(また時には着実に増え続ける)プレッシャーに耐えられるだけの精神的なスタミナを持っているか、をつなぎあわせるものである。もし彼に耐性がないならば、彼は有用であり続けるかもしれないが、作戦は短期間のものにしなければならない。 |

| 敵は彼を信頼しているか? | 敵が彼を信頼しているかどうかを示すものは、彼に与えられた通信システムのレベル、勤続年数、階級、与えられた訓練の種類や内容の中に見つかることがある。もし敵がそのエージェントと距離を置いているならば、彼を二重スパイとして採用することによって大きな見返りが得られる可能性はほとんどない。 |

| 彼との連絡をどちらの側からも管理下に置くことができるか? | 連絡を管理下に置くことはこちら側にあっても十分難しいが、特にエージェントが敵の領地に住んでいる場合はなおさらである。しかし敵のチャンネルを管理下に置くことは最善の状況ですら難しい。そのためには時間、技術、そしていつもの通り、マンパワーが必要となる。 |

これらの質問に対して、1つもしくは2つの否定的な答えがあったからといって、作戦が実行不可能であるとしてただちに拒絶される根拠にはならない。But they are ground for requiring some unusually high entries on the credit side of the ledger.

最初の選考は穏やかな雰囲気で行われるデブリーフィングまたは面接によって行われる。面接官はリラックスしたカジュアルな格好をしているかもしれないが、彼のそうした表面的な態度の裏には入念に考え抜かれた目的がある。彼は対象となる人物の目的に対する動機、情緒の状態と精神的なプロセスについて最初の判断をしようとしている。

例えば、もし他の諜報機関の職員であった離反者が自らの善意を表すために他の諜報機関の職員なら絶対に明かさないようなとても敏感な情報を明らかにしながら接近してきた場合、そこには2つの可能性がある。

●離反者が真実を語っているか

●または挑発しようとしているか

のどちらかである。

時にはその人物の態度が、2つの可能性のうちどちらであるかを想起させることもある。さらにその人物の正体を特定し、彼に関する資料を調査するため、離反者が所属していた機関についての情報を獲得する必要もある。

動機とは精神と感情衝動の複合体であるから、エージェントがどのような人物でどのような活動を代表しているのかを立証するよりも、エージェントがなぜ自分自身を代表しているのかを判断する方が難しいかもしれない。二重スパイとなる動機への疑問は、面接官が2つの観点から判断しようと試みる。

●エージェントによる理由の説明と、

●面接官が彼の言っていることや振る舞いから推理する。

志願者が民主主義的なイデオロギーを尊重することについて語ることもあるかもしれないが、西側諸国の歴史や政治についての会話は潜在的な二重スパイが民主主義について真に理解していないことを明らかにするかもしれない。イデオロギーは彼が協力しようとしている本当の動機ではないかもしれない。そのような人物が民主主義についてのロマンティックな作り話を創作しているということもありえるかもしれないが、彼は自分が考える防諜の職員が聞きたいと思っていることを言っているのだと考えるほうがより現実的である。防諜の職員は志願者が基本的な動機、金銭または復讐、について心地よく言及することができるようにしなければならない。そのようなものをエージェントがそれらを見ることができるところに贅沢なカタログとして置いておき、彼がどのように反応するか、願望、嫌悪感、または不信感を示すのかを観察することは有益である。

職員が動機が何であるかと考えることとエージェントがそれについて何を語っているかとの間で判断することは簡単なことではない、なぜなら二重スパイは広範囲で様々な動機に基づいて行動するからであり、時には自虐的な願望から双方から罰せられることを願望を持つ者さえいるからである。経済、宗教、政治、または復讐が動機である者もいる。最高の二重スパイは彼の僚友のために行うすべての行為によって毎日喜びを感じる者である[31]。

エージェントの心理学的および物理的な持続可能性の判断もまた困難なものである。時にはある理由から、心理学者または精神医が呼ばれることもある。そのような専門家、またはよく訓練された防諜の職員が二重スパイのなかに反社会性パーソナリティ障害の兆候を認識することもあるかもしれない。二重スパイの作戦の視点から、ここで鍵となる特徴は、

| 彼らはストレスがかかる状況ではたいてい穏やかで落ち着いてはいられないだけでなく、決まった作業や退屈な作業にも耐えることができない。 | 彼らは他人に対する態度が独善的であるために、形式的な、また大人の感情に基づいた他人との関係を持ち続けることができない。 |

| 彼らは平均以上の知能を持っている。彼らは言語が堪能であり、時には2つかそれ以上の言語を解する。 | 彼らは猜疑心が強く、他人の動機や能力については皮肉っぽくすらあるが、彼ら自身の競争力については誇大に評価している。 |

| 彼らがエージェントとして信頼できるは、主にどの程度、上司の指示が彼らの最大の興味と一致していると考えられるかによって決まる。 | 彼らが望むのは短期的に得られるものだけである。彼らは多くを望み、彼らはそれを今欲している。遠い将来の報酬を得るためにこつこつ努力を続けるような忍耐強さは彼らにはない。 |

| 彼らには秘密裏に物事を行うことが生まれつきであり、自分の目的を隠し、他人を欺くことを楽しんでいる。 |

志願者はひとりの人間として、また作戦を行う可能性がある者であるとして考慮されなければならない。手に余るものとして拒否された者が、防諜機関または二重スパイおよびその事例の両方について独立した見方を獲得し維持するための地位に就くことを受け入れることがある。

作戦の潜在的価値の推測には彼がふさわしい資質、施設、技術的支援を備えた人物であり、作戦を継続することによって彼の本国政府の他の活動に損害を与えることができるかどうか、遅かれ早かれ外国のとの連絡所の事例について共有することが必要であり、また望ましいものであるかどうか、そして事例が政治的な意味を包摂しているかどうかが考慮されなければならない。

攻撃的カウンターインテリジェンスの作戦の類型[編集]

攻撃的カウンターインテリジェンスの目的は組織に忠誠を誓うことから始まる。これらは以下のような例にまとめることができる。 ●組織A‥外国の諜報機関︵FIS︶または国家に基づかない集団 ●組織A1‥Aのクライアント、支援組織または同盟国 ●組織B‥自国または同盟国の組織 ●組織B1‥Bのクライアント、支援組織、または同盟国 ●組織C‥この文脈において中立的であると考えられる第三国の組織。 二重スパイと離反者はすぐに感情的な葛藤を生み出すかもしれない組織Bに忠誠を誓うことから始める。偽旗作戦もまた葛藤を生み出す可能性を秘めている。これらの作戦では組織Cに所属していると思われている人々を採用するが、彼らが真実を語っていないためである。彼らは実際には作戦の性質により組織AまたはBのために活動する。モール[編集]

モール︵もぐら︶は組織Aに忠誠を誓うことから始めるが、諜報員として訓練を受けている場合と受けていない場合とがある。実際には彼らは訓練を受けていないが外国の諜報機関に浸透していく意思があり、そのリスクも理解していない場合、または類まれな勇敢な人物で、B国に対する高い関心があり、限られた準備のために本当に忠誠を誓っている組織が明らかになった場合に報復を受けるリスクを負うことをいとわない場合とがある。 組織Aから始め 組織Bに加入し 組織Aに報告する、またはその組織を離れるか組織が崩壊するまで作戦を混乱させる。 留意すべきことは、プロフェッショナルの諜報員のなかには、敵の諜報機関の作戦、技術、軍事作戦について重要な情報を得るため、敵の組織の人物と個人的な関係を築くためモールとしての役割を受け入れる者もいるということである。そのような人物は事務員や宅配業者を装い多くの書類を撮影したりするが、実際にはそうではなく、敵が何を考えているかを探ることが目的であり、そのためのモールは一般的な人的な資産となる。 整理すると、すべてのモールは人的な資産であるが、すべての人的な資産がモールであるわけではない。 より困難な方法のひとつには、敵の諜報機関︵またはテロリスト集団︶が﹁離反﹂の構えを取っている︵自主的に情報を提供としようとしている︶敵の諜報員を採用しようとする場合の﹁どっちつかず﹂のモールがある。 他の特別な事例を挙げると、時に若い年齢で組織に入るが、上級の地位につくまで明らかに報告したり疑いを持たれるような何かをしたりすることなく活動する﹁深く潜伏した﹂あるいは﹁スリーパー﹂と呼ばれるモールがある。キム・フィルビーは彼が既に共産主義に染まってからイギリス政府に採用され活動したエージェントの例である。偽旗浸透[編集]

特殊な事例として、偽旗作戦によって組織に浸透する場合が挙げられる。 組織Cに所属することから始め、 組織Aに採用されたと思い込み、 実際には組織Bによって採用され、嘘の情報を組織Cに送る。離反者[編集]

組織を離れることを望む人物、そのような者は時には高いレベルの地位にある者、または経済的な困窮によって露見するリスクの少なかった者であることもあるが、そのようの人物は進んで捕らわれようとやって来る。たとえそうであったとしても、離反者は確かに情報を携えており、そして資料や他の価値のあるデータをもたらすこともある。 組織Aに所属することから始め、 組織Aを離れ、組織Bに行く。そのままの離反者[編集]

別の方法として、敵の諜報機関︵またはテロリスト集団︶における地位に相当する範囲内で敵に直接採用される場合、または諜報員︵またはテロリスト︶の活動を維持しながら自らが所属する組織に対するスパイ行為を行う場合が挙げられる。これは﹁エージェント﹂または﹁そのままの離反者﹂としても知られる。[22] 組織Aに所属することから始め、 組織Aで活動を続けながら組織Bに情報を流す。二重スパイ[編集]

二重スパイの作戦運用について考えを巡らせる前に、諜報機関はその人的資源について考えなければならない。そのエージェントを管理するには、現地の職員、工作官と幹部レベルの双方において技術と洗練性が必要とされるだろう。 諜報機関がその二重スパイを第二次世界大戦におけるダブルクロス・システムによって行われたように物理的に管理下に置くことができなければ、複雑さは天文学的に膨れあがる。 始まりから終わりに至るまで、二重スパイの作戦の運用は最大限の注意深さをもって計画され、実施され、そしてすべてについて報告されなければならない。そのような問題において、詳細についての量や管理する上で必要とされる支援は時に受け入れがたいとさえ思われる。しかし、浸透工作では支援が少ないことが常であるため、離反者が伝えることができる我々が知ることが必要なことは、時間が経つにつれて少なくなっていき、彼らに残された時間的制約のため、二重スパイはその現場に携わる者の一員として活動を続けていく。[17] 海外で行われる活動、特に警察が中立的あるいは敵対的である地域で行われるものもまた、鋭い専門性が必要とされる。[31] 工作官はエージェントの母国の地理や言語のニュアンスについて知っておかなければならない。工作官はエージェントのコミュニケーションにおける微妙な感情表現を理解し、どのようなものであれ情報の詳細について確認する必要があるため、通訳を用いることは極めて愚かな状況である。工作官は自国、同盟国、または敵国の関連法について知っている必要があり、作戦の成否はそれにかかっている。工作官はたとえ友好国においてであっても、通常警察官はエージェントに対して疑念を持ち尋問するものであるため、作戦を成功させるため、その地域の法執行機関や治安部隊との調整力および知識を持っている必要がある。 最も望ましいのは、二重スパイのコミュニケーションを完全にコントロールしている下で行われている状況である。通信がモールス符号で行われていた頃は、運用者は﹁こぶし﹂と呼ばれるユニークな符合のリズムを持っていた。マシントの技術の時代では、運用者個人によって認識していたため、異なるエージェントに交代することは不可能だった。エージェントもまた、意図的あるいは微妙な変化によって彼が立場を変えたことを伝えるための合図を送ることができた。 モールス信号が使われなくなる一方、その代わりとして声紋認識が採用されることが多くなった。文書による通信でも、文法または語彙の選択にはパターンがあり、エージェントが元々どの組織に所属していたのかについて知ることができ、それによって発覚する危険を回避することができる。 ︵エージェントの︶過去の︵そして特に以前所属していた諜報機関に関する︶全ての情報は、彼の行動パターン︵個人的および国家の組織の構成員としての︶に関する動かしがたい証拠となり、彼との関係について理解することができる。 組織への浸透に成功した敵の諜報員を発見することは、浸透された諜報機関に発見した諜報員を二重スパイとして利用するために転向させる可能性を提供する。二重スパイとして活動を開始することは、生涯を通じてその作戦に深く影響を与える。彼らはほとんどすべて以下の3つの方法から活動を開始する。 ●自発的にエージェントとなる者 ●発見され、通常は強要されて二重スパイとなる者 ●挑発エージェント 二重スパイ 組織Aから始め、 組織Bに採用される。 組織Aを裏切り、彼が知っているすべてを組織Bに伝え、 二重スパイとして活動しながら組織Aに関する情報を組織Bに伝え続ける。 偽旗二重スパイ 組織Aから始め、 組織Cに所属し、 エージェントが実際には組織Bが情報を入手しているにもかかわらず、誤った情報によってあたかも組織Cに話していると思い込ませる状況を組織Bが作る。 積極的浸透工作員 組織Aから始め、実際に組織Aに忠誠を誓い、 組織Bに行き、組織Aのために活動するが転向したいと言い、組織Bに彼と組織Aとのコミュニケーションチャンネルへのアクセスを開示し、 組織Bが知らない組織Aとのつながりを維持する副次的コミュニケーションチャンネルXを保ったまま、 Xを通じて組織Bの作戦技法について組織Aに報告し、 Xを通じてう情報を嘘の組織Aから組織Bに流す。 受動的プロバカートル 組織Aは組織Cに対して分析を行い、どのターゲットが組織Bにとって何が魅力的なのかについて決断する。 そして組織Aは組織Bに忠誠を誓うと思われる組織Cの人員をリクルートする。 組織Aがリクルートした、組織Cの人員は、組織Bに対して貢献的である。 組織Aは組織Cの人員の浸透により組織Bの内情を知ることが可能となり、組織Bと組織Cの関係を傷つけることができる。 これを完遂することは非常に困難であり、もし達成できたとしても、本当の困難はこの﹁転向した資産﹂をコントロールし続けることにある。転向した敵のエージェントをコントロールすることは、エージェントの新たな忠誠心が一貫したものであるかどうかを見極めるということに本質的に要約される多様な側面を持った複雑な実践であり、つまりそれは二重スパイの転向が本物であるか偽のものであるかを意味する。しかしながら、このプロセスは全く一筋縄ではいかず、不確実性と疑念を伴うことがある。 テロリスト集団に関しては、所属していた組織を裏切ったテロリストは、外国の諜報機関を裏切った諜報員とほとんど同じ方法で、以前所属していた組織に対する二重スパイとなることがありうる。そのため、その危険性を和らげるため、一般的に二重スパイが所属していたテロリスト集団に対して活動する場合にはどのように活用するのがよいか方法が話し合われる。[22] 二重スパイとは、2つの諜報またはセキュリティ機関︵またはそれ以上の共同作戦︶に秘密裡に従事し、1つの機関または従事する複数の機関それぞれにその他の機関の情報を提供する人物であり、他の機関の指示によって意図的に極めて重要な情報を渡さなかったり、またはある機関に意図せずして操作されることがあるため、極めて重要な事実は敵の諜報機関からは差し控えられる。情報を言いふらす人物、虚偽の情報を生み出す人物、そして組織のためでなく自分自身のために活動するような人物はエージェントではないため二重スパイではない。両方の側からエージェントとしての関係を持つ二重スパイは、通常目標とする機関の職員として配置される浸透工作とは区別される。 意図せずして二重スパイとなる者は極めて稀である。エージェントが実際には敵を欺いていながら敵の利害にダメージを与えているときにその機関を仕えていると考えさせるときに必要とされる操作スキルは明らかに最高位に位置する。 作戦が成功するか予測するために最も重要な手がかりは、エージェントが最初にまたは前にどこに所属していたか、それが自由意志で形成されたものであるかどうか、その期間の長さ、そしてその階級の程度にある。敵との秘密の関係が何年もの間続くことの影響は深く微妙であり、機関Bの工作官と機関Aの二重スパイが共同で作業することは民族性または宗教によって特徴づけられ、たとえエージェントがAの政府に嫌悪感を抱いていても、そのような絆が深くなることがあるかもしれない。機関Bの工作官が二重スパイのことを深く思いやることもあるかもしれない。 長期にわたる秘密作戦のもうひとつの産物は、ほとんどの作戦においてエージェントをコントロールすることが難しくなるかもしれないことである。工作官が優れた訓練と経験を彼に与えたことによりエージェントは工作官の優位性を決断させ、この優位性を認識することにより工作官はエージェントをより扱いやすくなる。しかし事実を付け加えると、経験が豊富な二重スパイは米国での経験よりも長いビジネス経験を持っているかもしれず、少なくとも2つの異なる機関で勤務したことにより直接比較できる知識を得たことにより彼はさらなる優位性を持つことになる。そして明らかなのは工作官の優位性はマージンは減少し、消滅するか、あるいは覆されさえする。 One facet of the efforts to control a double agent operation is to ensure that the double agent is protected from discovery by the parent intelligence service; this is especially true in circumstances where the double agent is a defector-in-place. Like all other intelligence operations, double agent cases are run to protect and enhance the national security. They serve this purpose principally by providing current counterintelligence about hostile intelligence and security services and about clandestine subversive activities. The service and officer considering a double agent possibility must weigh net national advantage thoughtfully, never forgetting that a double agent is, in effect, a condoned channel of communication with the enemy.配置された二重スパイ[編集]

A service discovering an adversary agent may offer him employment as a double. His agreement, obtained under open or implied duress, is unlikely, however, to be accompanied by a genuine switch of loyalties. The so-called redoubled agent whose duplicity in doubling for another service has been detected by his original sponsor and who has been persuaded to reverse his affections again also belongs to this dubious class. Many detected and doubled agents degenerate into what are sometimes called "piston agents" or "mailmen," who change their attitudes with their visas as they shunt from side to side. Operations based on them are little more than unauthorized liaison with the enemy, and usually time-wasting exercises in futility. A notable exception is the detected and unwillingly doubled agent who is relieved to be found out in his enforced service to the adversary.能動的工作員[編集]

There can be active and passive provocation agents. A double agent may serve as a means through which a provocation can be mounted against a person, an organization, an intelligence or security service, or any affiliated group to induce action to its own disadvantage. The provocation might be aimed at identifying members of the other service, at diverting it to less important objectives, at tying up or wasting its assets and facilities, at sowing dissension within its ranks, at inserting false data into its files to mislead it, at building up in it a tainted file for a specific purpose, at forcing it to surface an activity it wanted to keep hidden, or at bringing public discredit on it, making it look like an organization of idiots. The Soviets and some of the Satellite services, the Poles in particular, are extremely adept in the art of conspiratorial provocation. All kinds of mechanisms have been used to mount provocation operations; the double agent is only one of them. An active one is sent by Service A to Service B to tell B that he works for A but wants to switch sides. Or he may be a talk-in rather than a walk-in. In any event, the significant information that he is withholding, in compliance with A's orders, is the fact that his offer is being made at A's instigation. He is also very likely to conceal one channel of communication with A-for example, a second secret writing system. Such "side-commo" enables A to keep in full touch while sending through the divulged communications channel only messages meant for adversary eyes. The provocateur may also conceal his true sponsor, claiming for example (and truthfully) to represent an A1 service (allied with A) whereas his actual control is the A-a fact which the Soviets conceal from the Satellite as carefully as from us.受動的工作員[編集]

Passive provocations are variants involving false-flag recruiting. In Country C, Service A surveys the intelligence terrain through the eyes of Service B (a species of mirror-reading) and selects those citizens whose access to sources and other qualifications make them most attractive to B. Service A officers, posing as service B officers, recruit the citizens of country C. At some point, service A then exposes these individuals, and complains to country C that country B is subverting its citizens. The stake-out has a far better chance of success in areas like Africa, where intelligence exploitation of local resources is far less intensive than in Europe, where persons with valuable access are likely to have been approached repeatedly by recruiting services during the postwar years.[31]多様に転身する諜報員[編集]

A triple agent can be a double agent that decides his true loyalty is to his original service, or could always have been loyal to his service but is part of an active provocation of your service. If managing a double agent is hard, agents that turned again (i.e., tripled) or another time after that are far more difficult, but in some rare cases, worthwhile. Any service B controlling, or believing it controls, a double agent, must constantly evaluate the information that agent is providing on service A. While service A may have been willing to sacrifice meaningful information, or even other human assets, to help an intended penetration agent establish his bona fides, at some point, service A may start providing useless or misleading information as part of the goal of service A. In the World War II Double Cross System, another way the British controllers (i.e., service B in this example) kept the Nazis believing in their agent, was that the British let true information flow, but too late for the Germans to act on it. The double agent might send information indicating that a lucrative target was in range of a German submarine, but, by the time the information reaches the Germans, they confirm the report was true because the ship is now docked in a safe port that would have been a logical destination on the course reported by the agent.[32] While the Double Cross System actively handled the double agent, the information sent to the Germans was part of the overall Operation Bodyguard deception program of the London Controlling Section. Bodyguard was meant to convince the Germans that the Allies planned their main invasion at one of several places, none of which were Normandy. As long as the Germans found those deceptions credible, which they did, they reinforced the other locations. Even when the large landings came at Normandy, deception operations continued, convincing the Germans that Operation Neptune at Normandy was a feint, so that they held back their strategic reserves. By the time it became apparent that Normandy was indeed the main invasions, the strategic reserves had been under heavy air attack, and the lodgment was sufficiently strong that the reduced reserves could not push it back. There are other benefits to analyzing the exchange of information between the double agent and his original service, such as learning the priorities of service A through the information requests they are sending to an individual they believe is working for them. If the requests all turn out to be for information that service B could not use against A, and this becomes a pattern, service A may have realized their agent has been turned. Since maintaining control over double agents is tricky at best, it is not hard to see how problematic this methodology can become. The potential for multiple turnings of agents and perhaps worse, the turning of one’s own intelligence officers (especially those working within counterintelligence itself), poses a serious risk to any intelligence service wishing to employ these techniques. This may be the reason that triple-agent operations appear not to have been undertaken by U.S. counterintelligence in some espionage cases that have come to light in recent years, particularly among those involving high-level penetrations. Although the arrest and prosecution of Aldrich Ames of the CIA and Robert Hanssen of the FBI, both of whom were senior counterintelligence officers in their respective agencies who volunteered to spy for the Russians, hardly qualifies as conclusive evidence that triple-agent operations were not attempted throughout the community writ large, these two cases suggest that neutralization operations may be the preferred method of handling adversary double agent operations vice the more aggressive exploitation of these potential triple-agent sources.[22] Triple agent Starts out working for B Volunteers to be a defector-in-place for A Discovered by B Offers his communications with A to B, so B may gain operational data about A and send disinformation to A A concern with triple agents, of course, is if they have changed loyalties twice, why not a third or even more times? Consider a variant where the agent remains fundamentally loyal to B Quadruple agent Starts out working for B Volunteers to be a defector-in-place for A. Works out a signal by which he can inform A that B has discovered and is controlling him Discovered by B Offers his communications with A to B. B actually gets disinformation about A's operational techniques A learns what B wants to know, such as potential vulnerabilities of A, which A will then correct Successes such as the British Double Cross System or the German Operation North Pole show that these types of operations are indeed feasible. Therefore, despite the obviously very risky and extremely complex nature of double agent operations, the potentially quite lucrative intelligence windfall – the disruption or deception of an adversary service – makes them an inseparable component of exploitation operations.[22] If a double agent wants to come home to Service A, how can he offer a better way to redeem himself than recruiting the Service B case officer that was running his double agent case, essentially redoubling the direction of the operation? If the case officer refuses, that is apt to be the end of the operation. If the attempt fails, of course, the whole operation has to be terminated. A creative agent can tell his case office, even if he had not been tripled, that he had been loyal all along, and the case officer would, at best, be revealed as a fool. Occasionally a service runs a double agent whom it knows to be under the control of the other service and therefore has little ability to manipulate or even one who it knows has been successfully redoubled. The question why a service sometimes does this is a valid one. One reason for us is humanitarian: when the other service has gained physical control of the agent by apprehending him in a denied area, we often continue the operation even though we know that he has been doubled back because we want to keep him alive if we can>. Another reason might be a desire to determine how the other service conducts its double agent operations or what it uses for operational build-up or deception material and from what level it is disseminated. There might be other advantages, such as deceiving the opposition as to the service's own capabilities, skills, intentions, etc. Perhaps the service might want to continue running the known redoubled agent in order to conceal other operations. It might want to tie up the facilities of the opposition. It might use the redoubled agent as an adjunct in a provocation being run against the opposition elsewhere. Running a known redoubled agent is like playing poker against a professional who has marked the cards but who presumably is unaware that you can read the backs as well as he can.[31]脚注[編集]

(一)^ ﹁カウンターインテリジェンス﹂﹃日本大百科全書﹄小学館、コトバンク。2021年4月3日閲覧。

(二)^ Johnson, William (2009). Thwarting Enemies at Home and Abroad: How to be a Counterintelligence Officer. Washington DC: Georgetown University Press. pp. 2

(三)^ Executive Order 12333. (1981, December 4). United States Intelligence Activities, Section 3.4(a). EO provisions found in 46 FR 59941, 3 CFR, 1981 Comp., p.1

(四)^ Philip H.J. Davies (2012). Intelligence and Government in Britain and the United States: A Comparative Perspective. ABC-CLIO

(五)^ Anciens des Services Spéciaux de la Défense Nationale ( France )

(六)^ "Okhrana" literally means "the guard"

(七)^ Okhrana Britannica Online

(八)^ Ian D. Thatcher, Late Imperial Russia: problems and prospects, page 50

(九)^ “SIS Or MI6. What's in a Name?”. SIS website. 2008年7月11日閲覧。

(十)^ Christopher Andrew, The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of Mi5 (London, 2009), p.21.

(11)^ Calder Walton (2013). Empire of Secrets: British Intelligence, the Cold War, and the Twilight of Empire. Overlook. pp. 5–6

(12)^ Lowenthal, M. (2003). Intelligence: From secrets to policy. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

(13)^ Archick, Kristen (2006年7月24日). “European Approaches to Homeland Security and Counterterrorism” (PDF). Congressional Research Service. 2007年11月5日閲覧。

(14)^ “Counterintelligence Investigations”. 2008年5月8日閲覧。

(15)^ Dulles, Allen W. (1977). The Craft of Intelligence. Greenwood. ISBN 0-8371-9452-0. Dulles-1977

(16)^ abWisner, Frank G. (1993年9月22日). “On "The Craft of Intelligence"”. 2007年11月3日閲覧。

(17)^ abcMatschulat, Austin B. (1996年7月2日). “Coordination and Cooperation in Counerintelligence”. 2007年11月3日閲覧。

(18)^ “Joint Publication 3-07.1: Joint Tactics, Techniques,and Procedures for Foreign Internal Defense (FID)” (PDF) (2004年4月30日). 2007年11月3日閲覧。

(19)^ ab“National Counterintelligence Executive (NCIX)” (PDF) (2007年). 2015年1月22日閲覧。

(20)^ Suvorov, Victor (1984). “Chapter 4, Agent Recruiting”. Inside Soviet Military Intelligence. MacMillan Publishing Company

(21)^ abUS Department of the Army (1995年10月3日). “Field Manual 34-60: Counterintelligence”. 2007年11月4日閲覧。

(22)^ abcdeGleghorn, Todd E. (2003年9月). “Exposing the Seams: the Impetus for Reforming US Counterintelligence” (PDF). 2007年11月2日閲覧。

(23)^ US Department of Defense (2007年7月12日). “Joint Publication 1-02 Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms” (PDF). 2007年10月1日閲覧。

(24)^ Imbus, Michael T (2002年4月). “Identifying Threats: Improving Intelligence and Counterintelligence Support to Force Protection” (PDF). 2007年11月3日閲覧。

(25)^ Joint Chiefs of Staff (2007年6月22日). “Joint Publication 2-0: Intelligence” (PDF). 2007年11月5日閲覧。

(26)^ Intelligence Community Staff (1990年4月12日). “Project Slammer Interim Progress Report”. 2007年11月4日閲覧。

(27)^ abStein, Jeff (July 5, 1994). “The Mole's Manual”. New York Times 2007年11月4日閲覧。

(28)^ Security Policy Advisory Board (1997年12月12日). “Security Policy Advisory Board Meeting Minutes”. 2007年11月4日閲覧。

(29)^ “Canadian Forces National Counter-Intelligence Unit” (2003年3月28日). 2007年11月19日閲覧。

(30)^ “Security Intelligence Liaison Program” (2003年3月28日). 2007年11月19日閲覧。

(31)^ abcdeBegoum, F.M. (18 September 1995). “Observations on the Double Agent”. Studies in Intelligence 2007年11月3日閲覧。

(32)^ Brown, Anthony Cave (1975). Bodyguard of Lies: The Extraordinary True Story Behind D-Day

参考文献[編集]

- Field Manual No.2(FM 2-0) "Intelligence" (Department of the Army, 17 May 2004)

- Johnson, William R. Thwarting Enemies at Home and Abroad: How to Be a Counterintelligence Officer (2009)

外部リンク[編集]

- 日本においてロシア諜報機関に協力した情報提供者の類型化 - J-Stage 犯罪心理学研究 2017 年 55 巻 1 号 p. 29-45

関連項目[編集]

- 公安警察

- 秘密警察

- 防衛秘密の漏洩 - 自衛隊に於ける情報漏洩。

- 情報保全隊の市民活動監視問題 - 情報保全隊からの情報漏洩も問題となった。

- 秘匿通信

- インテリジェンス・サイクル・セキュリティ

- Irregular warfare

- List of counterintelligence organizations

- スメルシ (Soviet counter-intelligence, abbreviation of the phrase "Smash Spies")

- X-2 Counter Espionage Branch

- コインテルプロ