フランクとモンゴルの同盟

表示

フランクとモンゴルの同盟はフランク人 (この場合、フランク王国に由来を持ち、西方教会、特にローマカトリック教会に属する西ヨーロッパの諸国と、それら諸国が起こした十字軍によって建国されたレヴァント地域の十字軍国家 (ウトラメール)諸国のことを指す) とモンゴル人の間で模索された協力関係を言う。13世紀、彼らの共通の敵であるイスラム国家に対抗するため、フランク人による十字軍国家とモンゴルの帝国の間では様々なリーダーによって何度かの同盟に向けた試みが行われた。この当時、モンゴル人は既にキリスト教を一部受容しており、モンゴル宮廷に多くの有力なネストリウス派キリスト教徒が存在していたことから、このような同盟への動きは当然の成り行きであった。要因の一つには、伝説として永らく語り継がれていたプレスター・ジョン (多くの信者がある日聖地に十字軍の援軍として現れると信じていた、東方の神秘的王国の王[1][2]) の伝説の存在がある。フランク (前出の通り、十字軍研究の分野では西欧諸国とそれらのレヴァント十字軍によって成立した国家のことを指す[3]) には東方からの援軍について、提案を受け入れ易い背景が整っていたと言える。フランク人とモンゴル人は、イスラム教徒を共通の敵としていたが、数十年の間に多くの文書、贈り物、特使が交わされたにもかかわらず、しばしば提案された同盟締結は、ついに有効な同盟実現には至らなかった[1][4]。

西欧とモンゴルとの接触は、1220年頃に、教皇とヨーロッパ各国王から大ハーンのようなモンゴル皇帝へ時折送られた書簡から始まり、その後モンゴルに征服された旧ペルシャ地域のイルハン朝へと引き継がれた。交流は、モンゴルが服従と朝貢を要求するのに対して、西欧諸国はモンゴルにキリスト教西方教会への改宗を求めるというパターンを繰り返す傾向にあった。モンゴル人はアジアの全域で彼らの進出に伴って既に多くのキリスト教国家とイスラム国家を征服しており、イスラム国家であるアッバース朝とアイユーブ朝を徹底的に破壊し滅亡させてきたが、この後数世代の間、この地域の最後のイスラム国家であるエジプトのマムルーク朝とは戦わなかった。十字軍国家の一つであるキリキア・アルメニア王国の王ヘトゥム1世は、1247年にモンゴルに服属の姿勢を示すことによって独立保証を得ることに成功し、他の周辺キリスト教国家の君主にもモンゴルへの服従と提携について薦めたが、わずかに彼の義理の息子にあたるアンティオキア公国のボエモン6世の説得に成功したのみであった。ボエモン6世は1260年に同調し、モンゴルに服属している。アッコの聖ヨハネ騎士団に代表される近隣の他のキリスト教国家の君主達はモンゴル人に対してより懐疑的であったため、彼らを地域で最も重要な脅威として認識していた。そのため、アッコの騎士らはイスラム・マムルーク朝と歴史的にも奇妙な消極的同盟関係に係わっていった。その結果、1260年にマムルーク軍とモンゴル軍の間で戦われたアイン・ジャールートの戦いの際には、モンゴルを攻撃するために進軍してきたエジプト軍が十字軍国家領内を通過することを黙認している[5]。

1260年代中頃から、モンゴルは脅威を及ぼす敵国であるという見方から、イスラム教徒に対する潜在的同盟国へと西欧諸国の態度が変わり始めた。モンゴルはこれを最大限利用しようと考え、協力と引き換えに再征服したエルサレムをキリスト教国家に返還することを約束した。連携を強化しようとする試みはペルシャのモンゴル国家、イルハン朝の創始者であるフレグから彼の子孫であるアバカ、アルグン、ガザン、オルジェイトゥまで、歴代ハーンとの交渉を通じて続けられたが、いずれも成功しなかった。モンゴルは1281年から1312年の間に、キリスト教諸国との共同作戦として度々シリア攻撃を目論んだが、致命的な物流補給の難しさとして軍が到着するのに数ヶ月単位で時間がかかることが仇となり、結局、いかなる方法においても効果的な作戦行動を調整することが出来なかった[6]。やがて、モンゴル帝国は内乱のために崩壊していき、エジプトのマムルーク朝は十字軍国家からパレスチナとシリア全土を取り返すことに成功した。1291年のアッコ陥落の後、残った十字軍は、キプロス島へ退いた。騎士団の一部はタルトゥースの沖合にあるアルワード島に立てこもり、再度モンゴルとの共同軍事行動を計画し、タルトゥースに橋頭堡を確立する最後の試みを行ったものの失敗に終わった。イスラム教徒は島を包囲してこれに応じた。1302年 (1303年の秋の説もあり) アルワード島も陥落し、十字軍は聖地での最後の足場を失うこととなった[7]。

現代歴史家の間では、西欧とモンゴルの間の同盟がレヴァント地域に勢力の均衡を変えることに成功したかどうか、そして、それがフランク人にとって賢い選択であったかどうかについて議論されている[8]。伝統的に、モンゴル人は外部の第三国を臣下または敵国としてみなす傾向があり、同盟国のような中間的な概念はほとんどなかったと考えられている[9][10]。

背景 (1209–1244)[編集]

西欧諸国市民の間では、偉大なるキリスト教同盟国が東方からやって来るという噂や予言が永らく語り継がれていた。これらの噂は第1回十字軍 (1096年–1099年) と同時期には既に広まっており、十字軍が戦いに敗れた後にうねりとなって一般に伝播した。プレスター・ジョンとして知られている虚像に関する伝説が生まれ、彼の国ははるか彼方のインド、中央アジアにあるとされ、極端な例ではエチオピアですら彼の地と考えられていた。この伝説は十字軍兵士の士気を高めた。また、東方から来た一部の人々は、彼らが永らく待ち望んだプレスター・ジョンによって送られた軍であるかもしれないという希望から、快く受け入れられることとなった。1210年、キリスト教信者でナイマン部の君主であったクチュルク (当時既にナイマン部はチンギス・カン率いるモンゴル軍に破れ壊滅しており、彼は西遼に亡命し、君主耶律直魯古 (チルク) の女婿となっていた。後に西遼を簒奪し、モンゴルと戦って1228年に戦死。) の闘争の噂が西欧に届いた。噂では、クチュルクの軍は当時強大なイスラム国家であったホラズム・シャー朝 (君主はアラーウッディーン・ムハンマド) と戦っていた (実際にはクチュルクはホラズム朝を主敵としては戦っておらず、むしろハン位の簒奪時にはチルクに対抗するためホラズム朝と同盟さえしている[11]。その他、クチュルクは西遼の簒奪後はウイグル族のカラハン朝を攻撃しているが、実際にホラズム朝を攻撃し滅ぼしたのはモンゴルの将軍ジェベである) 。欧州ではクチュルクこそが神話のプレスター・ジョンではないかという噂が広まり、再び東方のイスラムと戦おうという気運が高まっていった[12]。

第5回十字軍 (1213年–1221年) の間、キリスト教徒はエジプトのディムヤート包囲に失敗して退いており、プレスター・ジョンの伝説はチンギス・カンに率いられた急速に拡大するモンゴル帝国の現実と混同されていった[12]。1219年–1221年には、モンゴルの侵略軍はマー・ワラー・アンナフル地域やペルシャ地域に侵入し、東イスラム世界を侵略し始めていた[13]。十字軍兵士の間で、﹁インドのキリスト教諸国の王﹂ (プレスター・ジョン本人か彼の子孫の1人であるデイビッド王) が東方からイスラム教徒を攻撃しており、十字軍への援軍に来る途中なのだと噂が広まった[14]。1221年6月20日付けの書簡で、ローマ教皇ホノリウス3世までもが﹁聖地を救うために極東から来ている軍隊﹂についてコメントしている[15]。

1227年、チンギス・カンが亡くなると、モンゴル帝国は彼の子孫によって4つの汗国に分割され、やがて内戦状態へと堕落していった。モンゴルの指導者達がモンゴルの首都カラコルムに戻り、次期大ハーンの地位を巡って相互に反目し合っている間に、北西のジョチ・ウルスでは、彼らのいとこに当たるバトゥによってヴォルガ・ブルガール侵攻が行われ、主にハンガリーとポーランド方面でヨーロッパを侵略、拡大していった。イルハン朝として知られる南西部は、チンギス・カンの孫にあたるフレグの指導下にあった。彼は彼の兄で大ハーンのモンケを支援し続けたため、ペルシャとエルサレム方面へ前進を続けると同時に、キプチャクとも戦った[16]。

1246年のグユクからローマ教皇インノケンティウス4世への書簡 (ペルシア語で書かれている)

西欧とモンゴル帝国の間の最初の公式な交流は、ローマ教皇インノケンティウス4世 (在位: 1243年–1254年) と大ハーンとの間で行われ、書簡文書を携えた特命全権公使は陸路で数年を掛けて目的地であるカラコルムに到達した。交流は、西欧がモンゴルにキリスト教西方教会への改宗を要請し、モンゴルが西欧に服属を要求することで応えるという西欧–モンゴル間の規則的パターンとなって開始された[9][17]。

1242年、チンギス・カンの後継者である大ハーン、オゴデイの死去に伴い、モンゴルのヨーロッパ侵略は一旦終了した。モンゴルでは大ハーンが亡くなると、帝国各地から次期大ハーンを選出するクリルタイを開催するため、有力モンゴル人達は首都カラコルムに呼び戻された[18]。その間、モンゴル軍の冷酷な西方への進軍は、ついにはエジプトのアイユーブ朝イスラム教徒と同盟して、自らも西へと進出していたホラズム・シャー朝をさらに西へと追いやった[19]。続く1244年、ホラズム朝はキリスト教徒からエルサレムを奪還した。その後のラ・フォルビーの戦いでの喪失の後、キリスト教国の諸王は新たな十字軍 (第7回十字軍) に備え始め、1245年6月、第1リヨン公会議でインノケンティウス4世によって宣言された[20][21]。エルサレムの喪失は、一部の西欧人に、モンゴルをキリスト教西方教会に改宗させることが出来たならば、キリスト教国の潜在的同盟国になりうる存在としてモンゴル人に目を向けさせることとなった[4]。

1245年3月、インノケンティウス4世は複数の教皇勅書を出し、その幾つかは﹁タタールの皇帝﹂宛にフランシスコ会のプラノ・カルピニを使節として送られた。今日この書簡は Cum non solum と呼ばれている (ラテン語文書では書物の題名という概念が発達していなかった時代、冒頭の数語 (インキピット) を用いて題名に代えるのが通例であり、この書簡のインキピットから命名された) が、この中でインノケンティウス4世は平和に対する欲求を表明し (モンゴルの語彙では﹁平和﹂と﹁服従﹂は同義語であることを知らなかったと思われる[22]) 、モンゴルの統治者がキリスト教徒に改宗し、キリスト教徒を殺すのを止めるよう依頼した[23]。しかし、新しいモンゴルの大ハーンとして1246年にカラコルムで即位したグユクは、ローマ教皇の服従とモンゴルの権威に対して西欧君主らの朝貢を要求する内容のみで回答した[24]。

そなた達は誠実な心をもって﹁私達はあなたに服従し奉仕します﹂と述べねばならない。汝自身と全ての封建王国の君主らは例外なく参内し、奉仕し付き従わねばならない!その上で私はそなた等の服従を認めるであろう。もしそなたが神の命令に従わないならば、そしてもし我々の命令に従わないならば、私はそなた等を我が敵国とみなすであろう。

教皇の予備交渉 (1245–1248)[編集]

—グユク・ハーンからインノケンティウス4世への書簡; 1246年[25]

1245年、インノケンティウス4世による2通目の書簡はドミニコ修道会に属するロンバルディアのアセリンによって伝えられた[26]。彼は1247年にカスピ海の近くでモンゴル軍の指揮官バイジュに会った。バグダード攻略を計画していたバイジュは、教皇の権威をかさに尊大な態度で接するアンセルムスら使節団に激怒して面会を拒否したものの[27]、同盟の可能性を歓迎して、彼の使節としてアイバクとサーキスを通じてローマにメッセージを送った。それから、彼らはインノケンティウス4世の手紙 Viam agnoscere veritatis とともに1年後にローマへ帰還した。そこにおいて、教皇は彼らの脅威をやめるよう、モンゴル人使節に訴えた[28][29]。

キリスト教封建国家の動き[編集]

「モンゴルのグルジア侵攻」も参照

イルハン朝のモンゴル軍が聖地の方面へ進撃を続けたため、都市という都市が次々とモンゴル軍の手に落ちた。典型的なモンゴルの侵略パターンは、各地域に降伏する機会を1度与えることになっていた。対象国が降伏を受け入れるならば、モンゴル軍はその地の民衆と兵士を彼らのモンゴル軍に吸収し、さらなる帝国の拡大のために彼らを利用した。降伏を受け入れない場合には、モンゴル軍は武力で屈服させるか、屈服させた上で誰彼構わず虐殺した[30]。モンゴル軍が近付くと、モンゴルによる支配 (降伏) か、もしくは徹底抗戦かの選択に直面し、いくらかのキリスト教国家も含む多くのコミュニティは前者を選んだ[31]。

1248年のスンバト (アルメニア軍司令官)からアンリ1世 (キプロス王)とイブラン家のジャン (イブラン家)への書簡

1220年、キリスト教国ジョージアは繰り返し攻撃され、1243年には、女王ルスダンは正式にモンゴルに降伏し、ジョージアはモンゴル軍征服下で服属しモンゴル属領となった[32]。キリキア・アルメニア王国のヘトゥム1世は1247年にモンゴルに服属して、その後数年の間、他の君主がキリスト教国とモンゴルの提携に参画することを奨励した[33][34][35][36][37]。彼はカラコルムのモンゴル宮廷に彼の兄にあたるスンバト (アルメニア軍司令官)を派遣した。スンバトの書いたモンゴル人に関する楽観的な書簡は、西欧諸国に大きな影響を与えた[38]。

アンティオキア公国[編集]

アンティオキア公国は最も初期の十字軍国家の1つであり、第1回十字軍の侵攻中の1098年に建国された。アンティオキア公ボエモン6世はモンゴルの時代が来たと感じていた。彼の義理の父にあたるヘトゥム1世の影響もあり、ボエモン6世も1260年にアンティオキアをフレグに服属させた[33][39][40]。モンゴルの行政官と駐屯軍がアンティオキアの首都に配置され、公国が1268年にマムルーク朝の軍によって解体されるまで駐屯は続いた[41][42]。ボエモン6世はまた、モンゴルとビザンチン帝国の間の関係を強化する方法として、ギリシア正教会総主教の座にエウティミウス2世を復権させることを認めるよう、モンゴルから要求された。フレグはこの忠誠と引き換えに、1243年にイスラム教徒によって奪われた全てのアンティオキア領をボエモン6世に与えた[43]。しかし、彼のこのモンゴルとの関係について1263年に追及された結果、ボエモン6世はエルサレム総主教のジャック・パンタレオン (後のローマ教皇ウルバヌス4世)によって一時的に破門されることとなった[44]。 1262年または1263年頃、マムルーク朝の王バイバルスはアンティオキア公国への攻撃を試みたものの、モンゴルの干渉によって阻まれた[45]。しかしこれ以降、年を追う毎にモンゴルは同様の支援を出来なくなっていった。1264年から1265年にかけてはモンゴルはビレジクのフロンティア砦を攻撃出来ただけだった。1268年、バイバルスはついにアンティオキア領を完全に制圧し、公国は170年の歴史に幕を閉じた[46][47]。 1271年、バイバルスはボエモン6世に書簡を送っており、彼に完全なる絶滅を匂わして脅し、モンゴルとの同盟を理由に彼を嘲っている。 我らの黄旗はそなたらの赤旗を跳ね返し、鐘の音は﹁アッラーフ・アクバル !﹂のタクビールに替えられた。 (中略) 間もなく、我らの攻城兵器がそなたらの城壁と教会に一撃を浴びせ、我らの剣がそなたらの騎士を家に帰らせるであろうと警告する。 (中略) それから、我らはアバカとそなたらの同盟が行使されるのか見ていよう。—バイバルスからボエモン6世への書簡; 1271年[48]

ボエモン6世はトリポリ伯国領以外のアンティオキア領を奪われ逃亡した (両国はボエモン6世が君主を兼ねる同君連合だった) が、それも1289年にマムルーク朝によって陥落された[49]。

ルイ9世 (聖ルイ) とモンゴル[編集]

詳細は「第7回十字軍」を参照

フランス王ルイ9世は、彼自身が起こした第7回十字軍を通してモンゴルと接触している。彼の最初の海外遠征の挑戦の間に、彼は1248年12月20日にキプロスで2人のモンゴル使節と面会している。彼らはイルハン朝のモースルからやってきたデイビッドとマークという名のネストリウス派の信者で、ペルシャのモンゴル軍指揮官イルジギデイの書簡を携えてきた[50]。書簡はそれまでの服従を迫るような内容と比較してより懐柔的なトーンで書かれており、イルジギデイの使者は、エジプトとシリアのイスラム教徒の軍が合流するのを防ぐ方策として、イルジギデイがバグダードを攻撃する間に、ルイ9世がエジプトに上陸攻撃してほしいと要請した[51]。ルイ9世は大ハーンのグユクの下にロンジュモーのアンドレを特使として派遣することで応えたが、特使がモンゴル宮廷に到着する前にグユクは酒色が過ぎたために急死してしまった。代わって面会したグユクの未亡人で摂政のオグルガイミシュは、ルイ9世への返礼として、贈り物と見下したような手紙を特使に与えたのみで返し、彼に毎年賛辞を送り続けるよう朝貢を命じた[52][53][54]。

アイユーブ朝エジプトに対抗するルイ9世の作戦は失敗に終わった。彼はイルジギデイの提案の通りエジプトへ上陸し、ディムヤートの包囲戦でディムヤートの占領に成功したが、マンスーラの戦いで全軍を失い、エジプト軍に捕虜にされてしまった。結局、莫大な身代金 (一部はテンプル騎士団からのローンで対応した) とディムヤート周辺の全ての占領した都市の返還と引き換えに、彼の解放交渉がなされた[55]。数年後の1252年に、ルイ9世はエジプトと同盟 (第7回十字軍の間にエジプトではクーデターが発生し、アイユーブ朝からマムルーク朝にとってかわった)してシリア攻撃を模索したが失敗し、1253年に、彼はイスマーイール派の暗殺教団とモンゴルとの間で再び同盟を模索した[56]。ルイ9世は、ヘトゥム1世の兄、アルメニア軍司令官スンバトがモンゴルのことを褒め讃える書簡を見倣って、自らもモンゴル宮廷にフランシスコ会のウィリアム・ルブルックを派遣した。しかし、モンゴルの大ハーン、モンケは1254年にウィリアムを通じて返書を返すだけで応じ、モンゴルへの国王の服従を求めた[57]。

ルイ9世は、1270年に彼自身2回目の十字軍 (第8回十字軍) を企てた。モンゴルのイルハン朝の君主アバカは、十字軍がパレスチナに上陸したら直ちに、軍事支援をしてほしいと書簡でルイ9世に要請したが、ルイ9世はパレスチナではなく現代のチュニジアにあたるチュニスに進軍した[58]。彼の思惑は明らかに、最初にチュニスを征服して、そこからエジプトのアレキサンドリアに到着するまで、海岸に沿って彼の軍隊を動かすことだった。フランスの歴史研究家のアラン・ドゥマルジェとジャン・リシャールは、この時、十字軍側は未だモンゴルとの調整の企てが完了しておらず、1270年の時点でルイ9世がアバカからのメッセージに対して彼の軍と十分に協議が出来ていないため、作戦を1271年に延期してほしいと問合せている最中で、シリアに代わってチュニスを攻撃したのかもしれないことを示唆している[59][60]。ビザンチン帝国皇帝、アルメニア、モンゴルのアバカからの使節がそれぞれチュニスに在陣していたが、ルイ9世の突然の病没によって、彼の十字軍遠征計画の継続は困難となり、終止符が打たれた[60]。伝説によると、彼の最後の言葉は﹁エルサレム﹂だった[61]。

イルハン朝との関係[編集]

フレグ (1256–1265)[編集]

フレグ・ハーン (チンギス・カンの孫) は、自ら認めるシャーマニズム信奉者であったが、それでもキリスト教に対して非常に寛容だった。彼の母ソルコクタニ・ベキや、彼の最愛の正妃ドクズ・ハトゥンと彼の最も親しい協力者の何人かは、ネストリウス派のキリスト教徒だった。麾下の重要な将軍の1人であるキト・ブカもナイマン族出身のネストリウス派キリスト教徒だった[4]。モンゴル族と彼らのキリスト教家臣団の間の軍事的協力は、1258年–1260年頃には相当な規模になっていた。フレグの軍は、アンティオキアのボエモン6世、アルメニアのへトゥム1世のキリスト教軍隊、キリスト教のジョージア人と共に、この時代で最も強力な2つのイスラム王朝 (バグダードとアイユーブ朝シリアのカリフ) を効果的に滅亡させた[16]。バグダード陥落 (1258)[編集]

詳細は「バグダードの戦い」を参照

イスラム教の開祖ムハンマドの叔父アッバース・イブン・アブドゥルムッタリブの玄孫にあたるサッファーフ (アブー・アル=アッバース・アブドゥッラー・イブン・ムハンマド・アッ=サッファーフ) によって設立されたアッバース朝は、749年の建国以降、アフリカ北東部、アラビア半島、近東地域を支配していたが、1258年の時点ではイラク中部の領域のみに縮小していた。バグダードはイスラムの宝石と讃えられ、世界で最も大きく最も強力な都市の1つであると考えられ、ほぼ500年間、アッバース朝のカリフの権力の座はバグダードに存在した。しかし、バグダードはモンゴルの攻撃を受けて1258年2月15日に陥落し、このことはイスラム世界においてしばしばイスラーム黄金時代の終焉としてイスラム史上の唯一の破滅的出来事と考えられた。キリスト教国のジョージア軍が城壁を破った最初の軍で、﹁彼らの破壊は特に凄まじかった﹂と後世の歴史家スティーヴン・ランシマンによって記述されている[62]。フレグがバグダードを征服した際、モンゴル軍は建物を破壊し尽くし、近隣の全てを燃やし、ほぼ全ての男、女、子供たちを大虐殺した。しかし、正妃ドクズ・ハトゥンの仲裁で、キリスト教系住民は助けられた[63]。

新しい﹁コンスタンティヌス1世とヘレナ﹂としてシリアの聖書に描か れたフレグとドクズ・ハトゥン[64][65]

アジアのキリスト教徒にとって、バグダードの陥落は祝うべき事態だった[66][67][68]。フレグとキリスト教信者である正妃は、キリスト教の敵に対抗する神の使徒と思われるようになり[67]、キリスト教会の象徴として位置づけられる、4世紀のローマ帝国においてキリスト教を公認したことでキリスト教の伝播に非常に強い影響力を及ぼしたコンスタンティヌス1世と、敬愛された彼の母 (皇太后) の聖ヘレナに比肩された。アルメニアの歴史家ギャンジャのキラコスはアルメニア教会のための聖句でモンゴル王室のカップルを称賛した[64][66][69]。また、シリア正教会の司教で文学者、歴史家でもあるバル・ヘブライウスもまた、彼らをコンスタンティンとヘレナと称し、フレグについて﹁知恵と気高さと輝かしい功績﹂で並ぶ者のない﹁王の中の王﹂であると述べている[66]。

シリア侵略 (1260)[編集]

バグダード陥落の後、1260年にモンゴル軍はキリスト教徒と共にイスラム勢力のアイユーブ朝の支配地域だったシリアを征服した。 彼らは1月には共同してアレッポの都市を奪取し、そして3月にはキリスト教徒でもあるモンゴルの将軍キト・ブカの指揮により、アルメニア軍を伴ったモンゴル軍とアンティオキアのフランク軍はダマスカスを奪取した[16][41]。アッバース朝とアイユーブ朝の両国の滅亡と共に﹁近東地域は二度と文明の中心となることは無かった﹂と、歴史家のスティーブン・ランシマンは述べている[70]。アイユーブ朝の最後のスルタンアン=ナースィル・ユースフはその後間もなく死亡し、イスラム社会の中心はバグダードとダマスカスを離れ、エジプトのマムルーク朝の首都カイロに移った[16][71]。モンゴル軍はエジプト方面への進撃を継続しようとした矢先、大ハーンのモンケが逝去したことにより撤退を余儀なくされた。フレグは大ハーンの地位の継承を狙っており、急いで首都カラコルムに戻り、彼の軍の大半を引き連れて権勢を誇る必要があった。そのため、彼の留守中、わずかな軍とともに将軍キト・ブカを残し、パレスチナ地域を占領させることとした。ガザに駐屯した約1,000名の守備隊からなるモンゴル軍はパレスチナをエジプト方面に向かい南へ送られた。[41][72][73]。アイン・ジャールートの戦い[編集]

詳細は「アイン・ジャールートの戦い」を参照

モンゴル軍とアンティオキアのキリスト教徒の協力にもかかわらず、レヴァント地域の他のキリスト教徒は、モンゴルの接近を不安をもって見ていた。エルサレム総主教のジャック・パンタレオン (後のローマ教皇ウルバヌス4世)は、モンゴル人をはっきりした脅威とみなし、1256年に彼らについて警告するために、教皇に手紙を書いた[74]。しかし、教皇は1260年にドミニコ修道会に所属するアシュビーのダビデをフレグの宮廷に派遣したのみであった[57]。シドンでは、シドンおよびボーフォート城の領主であったジュリアン・グルニエ伯 (彼は同時代の人によって無責任かつ思慮の浅い人物と評されている) は、モンゴルの領地であるベッカー高原地域を急襲して、略奪する機会を得た。この略奪で出たモンゴル人死者の1人にキト・ブカの甥がいた。キト・ブカは報復としてシドンの都市を急襲した。この出来事はモンゴルと、この時点で拠点の中心が沿岸都市であるアッコに移った十字軍勢力との間に不信の疑念を増すこととなった[75][76]。

アッコの十字軍はモンゴルとマムルーク朝の間で用心深く中立の立場を維持するため最大限の努力を尽くした[5]。マムルーク朝との永い抗争の歴史にもかかわらず、十字軍国家はモンゴルの方がより大きな脅威であると認め、慎重な議論の末、従来の敵とは消極的な休戦を結ぶことを選択しようと考えた。モンゴルから捕らえた馬を安価に購入する権利を得るのと引換えに、十字軍国家はマムルーク朝の軍隊がモンゴル攻撃のために北方へ向かう際に7キリスト教国家の領域を通過することを認めた[5]。この休戦の結果、マムルーク軍はほど近いアッコに宿営、再補給が許され、1260年9月3日、ついにアイン・ジャールートでモンゴル軍と交戦した。モンゴル軍はその主力がフレグとともに撤退していたため既に消耗している状態であり、十字軍国家の受動的な支援によって、マムルーク軍はモンゴルに対する決定的かつ歴史的な勝利を成し遂げることができた。戦いに敗れたモンゴル軍の残党は、ヘトゥム1世によって受け入れられ、再編成されて、キリキア・アルメニア王国に編入された[46]。モンゴル側から見ると局地戦かつ小規模な軍での戦闘であったとはいえ彼らが外敵に負けた初めての戦いであったため (厳密にはホラズムシャー朝のジャラールッディーンの軍団がモンゴルのシギ・クトク率いる3万騎を撃ち破ったアフガニスタンのパルワーンの戦いがあり、﹁初めて﹂ではない) 、モンゴルの歴史の大きなターニングポイントとなり、モンゴル帝国の止められないと思われた拡大に西の境界を設定することとなった[5]。

教皇グレゴリウス10世 (1210年–1276年) は、1274年 にモンゴルとの接触において、新たな十字軍を発布した[92]

教皇との通信[編集]

1260年代には、モンゴルに対するヨーロッパの認識に変化が生じ始め、彼らは敵としてではなく、イスラム教徒との戦いにおいて潜在的な同盟国たりうると見なすようになった[77]。1259年まで、教皇アレクサンデル4世はモンゴルに対抗して新たな十字軍を促していて、アンティオキアとキリキア・アルメニア王国の君主がモンゴルに冊封を受けたことを聞いて非常に失望していた。アレクサンデル4世は来るべき評議会の課題にこの2君主の件を加えようとしていたが、1261年、評議会が招集される直前に、新たな十字軍を起こすことも出来ず、急死した[78]。新任の教皇の選出が行われ、早くからモンゴルの脅威について警告を発していたエルサレム大司教のパンタレオンに決まった。彼は教皇ウルバヌス4世を名乗り、新たな十字軍設立のための資金を集めようとした[79]。 1262年4月10日、イルハン朝のハーン、フレグはフランスのルイ9世にハンガリーのジョンを通じて新しい書簡を送り、再び同盟の締結を要請した[80]。書簡は、以前はモンゴルは教皇がキリスト教徒のリーダーであるという印象の下にいたが、真の力はフランス国王にあることを理解した、と説明した。そして、教皇の利益のためにエルサレムを占領するというフレグの意向に言及し、エジプトに対抗して艦隊を派遣することが出来るかルイ9世に尋ねた。フレグはキリスト教徒のためにエルサレムを回復することを約束しつつ、一方でモンゴルの世界征服の探求においてモンゴルの主権は譲らないことも主張した。ルイ9世が書簡を実際にどう扱ったかは明確になっていないが、いくつかの点は教皇ウルバヌス4世に伝えられ、彼は前任者と類似した内容で回答した。彼の教皇勅書Exultavit cor nostrumの中で、ウルバヌス4世はフレグにキリスト教信仰に向けた親善の表現に対して歓迎の言葉を述べ、キリスト教への改宗を推奨した[81]。 歴史家は、ウルバヌス4世の行動の正確な意味について異議を唱えている。英国の歴史家ピーター・ジャクソンによって例証される主流派は、ウルバヌス4世はこの時点で未だモンゴルを敵として見なしていたと考えている。この認識は数年後にモンゴルが潜在的な同盟国であると見なされた時、教皇クレメンス4世の治世の間(1265年–1268年)に変わり始めた。しかし、フランスの歴史家ジャン・リシャールは、1263年という早い時期にウルバヌス4世のとった行動がモンゴルと欧州の関係のターニングポイントとなる引き金になり、以後モンゴルが実質的な同盟国と認識されるようになった、と主張している。リシャールはまた、ジョチ・ウルスのモンゴル族がイスラム・マムルーク朝と再び同盟を結んだことに対する反応として、西欧とイルハン朝のモンゴル族とビザンチン帝国の間の連合が形作られたと主張している[82][83]。しかし、歴史家主流派の共通の見方は、同盟を成立させるための多くの試みがなされたが、試みが不成功に終わったということである[1]。アバカ (1265–1282)[編集]

フレグが1265年に崩御した後はアバカ (1234年–1282年) が跡を継ぎ、西欧との協力の追求はさらに続行された。アバカは継承のため本来仏教徒であったが、東方正教会教徒でビザンチン帝国の皇帝ミカエル8世パレオロゴスの庶皇女マリア・パレオロギナと結婚した[84]。アバカは1267年と1268年を通して教皇クレメンス4世との外交を続け、使節をクレメンス4世とアラゴン王ハイメ1世に遣わした。クレメンス4世への1268年のメッセージでは、アバカはキリスト教徒を援助するために兵を出すと約束した。これが1269年に行われたアッコへのハイメ1世の遠征失敗に繋がったかどうかは不明である[14]。ハイメ1世は小規模な十字軍を始めようとしたが、彼ら地中海を横断を試みたところ、彼の艦隊を嵐が不意に襲い、大部分の船は引き返さざるを得なかった。ハイメ1世の十字軍は最終的には彼の2人の庶子フェルナンド・サンチェス・デ・カストロとペドロ・フェルナンデス・デ・イハルによって行われ、彼らは1269年12月にアッコに到達した[85]。アバカは、彼の初期の援助の約束にもかかわらず、トルキスタン方面からのジョチ・ウルスのホラーサーンへの侵入というもう一つの脅威 (ベルケ・フレグ戦争 ) に直面していたため、聖地奪還のためにはわずかな力を割くことのみに追われ、ほとんど何も出来なかったが、1269年10月に入るとシリア国境に沿って侵略の脅威を振りかざし始めた。遠からずして彼は10月にシリアのハラムとアパメアまで襲撃したが、バイバルスの軍が進撃してくるとすぐに退いた[39]。第9回十字軍 (1269–1274)[編集]

1269年、英国の若きエドワード皇太子 (後の英国王エドワード1世) は彼の大叔父にあたる獅子心王リチャードの、フランス王ルイ7世らと行った第2回十字軍の話に触発されており、彼自身の十字軍 (第9回十字軍) を始めた[86]。十字軍としてエドワードに同行した騎士と家来の数は極めて少なく、恐らく230人の騎士と、それを取巻く約1,000人の従者で、13隻の船からなる小艦隊で運搬された[49][87]。エドワードはモンゴルとの同盟の価値を理解しており、1271年5月9日のアッコへの到着と同時に、彼は直ちにモンゴルの統治者アバカに使者を送り、同盟を要請した[88]。アバカはエドワードの要請に積極的に応えた。そして、エドワードの軍に合流し、マムルークに対して攻勢に出るための10,000騎のモンゴル兵と共に将軍サマガル・ノヤンを派遣するため、彼の攻撃時期を調整するよう問合せてきた[39][89]。モンゴル軍の実体は、イルハン朝に服属するアナトリアのたった1万人ほどの騎兵軍であったが、とはいえ、キト・ブカの再来を思わせるモンゴル軍襲来の報がムスリム住民に与えた心理的恐怖は大きかった。モンゴル軍はアレッポのトルコ人防衛軍を破って南進し、アパメアまで襲撃した。一方、エドワードはその兵力の少なさから、かなり効果の少ない襲撃を行うことは出来ても、新たな領地を広げるような実質的な成功を収めることは出来なかった[86]。例えば、略奪のためにシャロン平野へ侵入した時、小さなマムルークの城砦カクンでさえ攻略できないと分かった[39]。しかし、かなり限定的ではあったけれども、エドワードの軍事作戦はアッコ市街とマムルーク朝の間で10年の休戦に同意するようにマムルーク朝君主バイバルスを説得するには役立ち、1272年に休戦協定が締結された[90]。エドワードの努力は、歴史家ルーヴェン・アミタイによって、﹁これまでに成し遂げられることになっていた、エドワードあるいは他の西欧の君主らによる本当のモンゴルと西欧の連携に最も近いもの﹂と言われた[91]。

第2リヨン公会議 (1274)[編集]

1274年、教皇グレゴリウス10世は2回目のリヨン公会議を招集した。アバカは13-16人のモンゴル代表団を送り、特にメンバーのうちの3名が公開の洗礼を受けた際、大きな物議を引き起こした[93]。アバカのラテン語通訳だったリカルドゥスは会議において、アバカの父フレグの下で以前の西欧とイルハン朝の関係を概説した中で、フレグがキリスト教国の使節を彼の宮廷に迎え入れた後、彼はハーンに対する彼らの崇拝と引き換えに、東方正教会のキリスト教徒に対して税と賦役の免除に同意したことを示す報告書を提出した。リカルドゥスによると、フレグはまた、西欧諸国の公館、使節に対する嫌がらせを禁止し、西欧諸国にエルサレムを返還することを約束した[94]。フレグの死の後についても、彼の息子アバカもまだシリアからマムルーク朝を追い出すと固く決心していたことを、リカルドゥスは会議の中で保証した[39]。 会議で、グレゴリウス10世は、彼の﹁信仰の熱意のための章典﹂における大いなる計画を整備し、以下の4つの要素を含む、モンゴルと連携した新たな十字軍の実行を発布した[92]。すなわち、3年間新しい税を課すこと、サラセン人 (この時代のイスラム教徒全般を指す) との貿易の禁止、イタリアの海洋共和国 (この時代以降に台頭するジェノヴァ、ヴェネツィア、ピサ、ラグサ等に代表される海上貿易を主要な収入源としたイタリアの共和国群)による船舶の補給協定、西方教会諸国とビザンチン帝国パレオロゴス家、モンゴルイルハン朝のアバカとの同盟締結、の4つである[95]。それから、アバカはジョージアのヴァサリ兄弟によって案内された別の使節も送り、西欧の君主達に軍の準備状況も通知した。グレゴリウス10世は、十字軍に彼の教皇大使を同行させ、イルハン朝との軍事作戦の調整を担当させるつもりであると応えた[96]。 しかし、教皇の計画は他の西欧の君主らには支持されず、十字軍に対する熱意は失われていった。ただ1人、西欧君主の中で初老のアラゴンのハイメ1世だけが直ちに十字軍を編成して派遣する事を主張したが、会議を動かすことは出来なかった。新たな十字軍派遣のための資金調達が計画されたが、完遂されなかった。この計画は1276年1月10日のグレゴリウス10世の死によって基本的に停止された。そして、この遠征に融資するために集められた資金は、代わりにイタリアで分配された[49]。シリア侵略 (1280–1281)[編集]

「モンゴルのシリア侵略」も参照

欧州諸国からの支援が得られず、十字軍国家 (ウトラメール、特にマルガット城に残る聖ヨハネ騎士団と、キプロスとアンティオキアのキリスト教国家) の一部の西欧人は、1280年–1281年にかけてモンゴルと協同作戦で結び付こうとした[96][97]。1277年、マムルーク朝のスルタン、バイバルスの死去はイスラム地域の混乱につながった。そして、聖地において他の派閥が新たな行動に出るための好機となった[96]。モンゴルはこの機会をつかんでシリアへの新たな侵略を計画し、1280年9月にバグラスとダルビサキを占領し、10月20日にはアレッポに到達した。アバカは、モンゴルの勢いを駆って、使節をイングランドのエドワード1世、アッコの十字軍、キプロスのユーグ3世 (キプロス王)とトリポリのボエモン7世 に派遣し、作戦に対する彼らの支持を要請した[98]。しかし、十字軍側は多くの援助を得るにも彼ら自身十分に組織されていなかった。アッコでは、教区牧師長が、都市は飢えのために損害を受けており、エルサレム王も別の戦争に既に巻き込まれていると応えている[96]。マルガット城 (以前アンティオキア公国、トリポリ伯国であった地域) の地元の聖ヨハネ騎士団は、1280年-1281年にかけて、マムルーク朝に占拠されたクラック・デ・シュヴァリエまでそう遠くないベッカー高原を襲撃することが出来た。アンティオキアのユーグ3世とボエモン7世は彼らの軍を動員したものの、彼らの軍隊はバイバルス死後の混乱を経て後継者の地位を獲得した新たなスルタン、カラーウーンの軍によって、モンゴル軍との連絡を阻まれた。カラーウーンは1281年3月にエジプトから軍を北に進め、十字軍とモンゴル軍の間に彼自身の軍を配置した[96][97]上で、1281年5月3日にアッコの騎士との10年間の休戦協定を更に10年10ヶ月更新し (彼自身がこの休戦を破棄することになるが)、潜在的同盟国を分断することに成功した[98]。彼はまた、1281年7月16日にトリポリのボエモン7世との間でも2回目の10年間の休戦協定を更新締結して、エルサレムへの巡礼者の出入りを認めた[96]。

1281年9月、モンゴル軍は彼ら自身の50,000騎に加えて、キリキア・アルメニア王国のレヴォン3世の30,000騎、ジョージアの軍、マルガット城の騎士200騎を引き連れて戻ってきた。そして、アッコの騎士団がマムルーク朝との休戦協定に同意していたにもかかわらず、彼らは部隊を送り込んだ[98][99][100]。モンゴル軍と彼らの同盟軍は1281年10月30日に第二次ホムスの戦いにおいてマムルーク軍と戦い、スルタンは大きな損害を被ったものの、対戦の決着は着かなかった[97]。報復として、カラーウーンは1285年にマルガット城の聖ヨハネ騎士団を包囲、占拠した[99]。

アルグン (1284–1291)[編集]

詳細は「アルグン」を参照

アバカは1282年に逝去し、ハーンの地位はイスラム教に改宗していた彼の弟テグデルに速やかに引き継がれた。テグデルは西欧との同盟を模索していたアバカの方針を翻し、その代わりに、マムルーク朝のスルタン、カラーウーンに同盟を求めた。カラーウーンはこの頃シリアへの進撃を続け、1285年に聖ヨハネ騎士団のマルガット城、1287年にラタキア、1289年にトリポリ伯国を占領していた[49][96]。しかし、テグデルのイスラム傾倒主義は支持が得られず、1284年に仏教徒でアバカの長男のアルグンが大ハーンのクビライの支持を取り付けて反乱を起こし、テグデルを処刑した。それから、Arghunは西欧との同盟の意向を復活させて、複数の使節を欧州各国へ派遣した[102]。

アルグンの最初の使節は、クビライ・ハンの西洋天文学部の長でネストリウス派の科学者イーサ・ケルメルチが送られた[103]。ケルメルチは1285年に教皇ホノリウス4世に謁見し、サラセン人 (イスラム教徒) を ﹁追い出して﹂、 ﹁偽りの地 (すなわち、エジプト)﹂を西欧人と分かち合おうと申し出た[102][104]。第2の (且つ、恐らく最も有名な) 使節は、高齢の聖職者ラッバーン・バール・サウマであり、彼は当時としては珍しい中国からエルサレムまでという巡礼の最中で、イルハン朝に滞在していた[102]。

バール・サウマと後のブスカレッロ・デ・ギゾルフィのような他の使節を通して、アルグンは、もしエルサレムが占領できた際には彼自身が洗礼を受け、キリスト教徒にエルサレムを返還するだろうと欧州の君主らに約束した[105][106][107]。バール・サウマは欧州の各国君主によって暖かく歓迎された[102]が、西欧諸国の十字軍や聖地奪還に対する関心は失われつつあり、同盟関係を構築する任務はついに実を結ぶことは無かった[108][109]。イングランドは外交代表として20年前のエドワード1世の十字軍の一員として従軍したジェフリー・オブ・ラングリーを送ることによって応え、1291年、イングランド大使としてモンゴルの宮廷に送られた[110]。

ジェノヴァの造船技師派遣[編集]

西欧とモンゴルの別の連携として、1290年、ジェノヴァ軍が海軍活動でモンゴル軍を援助しようとした際に試みられた。計画では、紅海でマムルーク朝の船を攻撃するために2隻のガレー船の建造と、船員の派遣を行い、インドとのエジプトの貿易を遮断する活動を行うことになっていた[111][112]。ジェノヴァは貿易面でマムルーク朝の伝統的な支持者であったため、これは明らかに1285年にキリキア・アルメニア王国へのマムルーク朝スルタン、カラーウーンの攻撃に起因する大きな方針変更だった[102]。艦隊を建造して船員を乗り込ませるために、総勢800人のジェノヴァ人大工、水夫、石弓射手の戦隊がバグダードに向かい、チグリス川で建造作業を開始した。しかし、教皇派と皇帝派の争いのため、ジェノヴァ人らはすぐに内部論争へと堕落し、バスラで互いを殺し合う自体に陥って計画は潰えた[111][112]。ジェノヴァはついに計画を取り消して、その代わりにマムルーク朝との新しい条約に調印した[102]。 これら全ての西欧とモンゴルの間で共同して攻撃を開始する試みは、あまりに小さく、あまりに遅かった。1291年5月、アッコの城塞都市はアッコ包囲戦の末、エジプトのマムルーク朝によって征服された。教皇ニコラウス4世がこれについて知った時、彼はアルグンに書簡を書き、洗礼を受けてマムルーク朝と戦うよう再度頼んだ[102]。しかし、アルグンは1291年3月10日に既に亡くなっていた。そして、教皇ニコラウス4世も1292年3月に亡くなり、彼らの連合した行動への努力は終止符を打った[113]。ガザン (1295–1304)[編集]

「モンゴルのシリア侵略」および「モンゴルのパレスチナ侵略」も参照

アルグンの死後、彼の2人の甥によって短命でかなり無力なハーン位の継承が矢継ぎ早に行われた。そして、その1人は数ヵ月の間ハーン位を維持しただけだった。1295年になって、他の有力なモンゴル君主からの協力を得たアルグンの長子ガザンが即位してようやく安定は回復され、ハーン位に着く際に、イスラム教への公式な改宗を行い、イルハン朝の国教において重要なターニングポイントとなった。しかし、公式にイスラム教徒になったにもかかわらず、ガザンは複数の宗教に寛容なままで、彼のキリスト教の属国であるキリキア・アルメニア王国やジョージアとの良い関係を維持することに取り組んだ[114]。

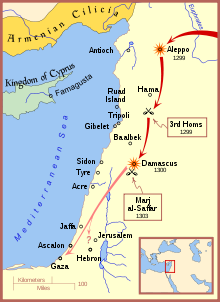

1299-1300年において、モンゴル軍はシリアの諸都市での戦い に従事し、ガザに程近いところまで南下、急襲した

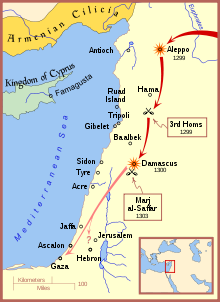

1299年、ガザンはシリアを侵略する3つの試みの最初の1手に着手した[115]。彼は新たな侵略の開始とともに、キプロスのキリスト教国家であるキプロスの王で軍の指揮権を持つアンリ2世 (エルサレム王)に書簡を送り、シリアのマムルーク軍の攻撃に援軍として合流するように誘った[116][117]。モンゴル軍は、アレッポの都市の獲得に成功し、彼らの属国キリキア・アルメニア王国の王ヘトゥム2世の軍と合流し、継続する攻撃に参加させた。1299年12月23日または24日、モンゴル軍は第三次ホムスの戦いで、マムルーク軍に完勝した[118]。シリアにおけるこの成功は、モンゴル軍が聖地の再占領に成功して、エジプトのマムルーク朝さえも征服し、北アフリカでチュニジア征服の作戦についたというでたらめな噂となってヨーロッパで広まった。しかし実際は、エルサレムは占領されるどころか、包囲されもしなかった[119]。実際には1300年前半にパレスチナへのいくらかのモンゴル軍の侵入だけが全てだった。襲撃はガザ近くまで到達し、いくつかの町を通り抜けており、恐らくエルサレムも含んだだろうと推測される。しかし、エジプト軍が5月にカイロから再び進撃を開始すると、モンゴル軍は抵抗することなく退いた[120]。

1300年7月、十字軍は制海権を得るために海軍活動を開始した[121]。キプロスのアンリ2世の命によりキプロスに16隻のガレー船と若干の小型船による艦隊が編成され、艦隊司令官として彼の兄弟アマルリック (ティルス公) と、ガザンの大使﹁チアリ (ピサのイソル)﹂が同行した[120][121][122]。船団は1300年7月20日にファマグスタを出航し、エジプトとシリアの海岸を襲撃し、キプロスに戻るまでに、ロゼッタ、アレキサンドリア、アッコ、タルトゥース、マラクーヤなどを襲った[120][122]。

アルワード島への遠征計画[編集]

詳細は「アルワード島の陥落」を参照

ガザンは1300年11月までに戻るであろうと発表して、十字軍側が準備が出来るように、西欧へ使節と書簡を送った。キプロス軍は彼ら自身で艦隊襲撃を行った後、以前のタルトゥースのシリアテンプル騎士団の拠点を取り戻すためにより大規模な作戦を企てた[6][117][123][124]。彼らは当時の時点で動員可能な最大限の兵力 (約600人の男性、アマルリック旗下の300騎とテンプル騎士団および聖ヨハネ騎士団からの同様の派遣部隊) を動員した。1300年11月、彼らは大陸本土のタルトゥースを占領しようとしたが、都市の支配を得ることは出来なかった。モンゴル軍は遅れた。その結果、キプロス軍は基地を確立するために沖合近くのアルワード島へ移り立てこもった[123]。モンゴル軍は遅れ続けた。そして、アルワード島の守備隊のみを残し、大半の十字軍兵力はキプロスに戻った[6][124]。1301年2月、ガザン率いるモンゴル軍は、ようやくシリアへの進撃を開始した。軍はアルメニア部隊として参加したモンゴルの将軍クトルグ・シャーと、イブラン家のギー、ジブレのヨハン2世 (ジブレの統治者)によって率いられた。しかし、60,000の兵を率いていたにもかかわらず、クトルーシュカはシリア周辺でいくらかの襲撃を行う以外、何も出来ずに撤退した[6]。

1303年のダマスカス攻撃の際、ガザンがアルメニア王ヘトゥム2世 にクトルグ・シャーを伴うよう命令する様子を描いたマルコ・ポーロの東方見聞録の細密画[125]

1301年-1302年にかけて、冬季攻勢をかけるためにモンゴルと西欧の共同作戦の計画が再度検討された。しかし、1301年秋頃、エジプトのマムルーク軍によるアルワード島への攻撃が行われた。長期にわたる包囲の末、アルワード島は1302年もしくは1303年に占領された[123][124]。マムルークは住民の多くを虐殺し、生き残ったテンプル騎士団を捕縛してカイロの牢獄へ送った[123]。1301年末、ガザンは教皇に書簡を送り、兵士、司祭、農民を送り、聖地を再び西欧の領地にするように頼んだ[126]。

1303年、ガザンはアルグンの外交官でもあったブスカレッロ・デ・ギゾルフィを通じて、エドワード1世に別の書簡を送った。書簡では、彼の祖先であるアバカが約束した、マムルーク朝への対抗を助け、西欧にエルサレムを返還することを再表明している。この年、モンゴル軍はアルメニア軍も伴って約80,000騎の大軍を動員し、シリアへの侵略を再度企てた。しかし、1303年3月30日にホムスで再び敗れ、1303年4月21日、ダマスカスの南のマージ・アル・サファーの戦いで決定的な敗北を喫した[57]。これがモンゴルによる最後の大規模なシリア侵略であると考えられている[127]。ガザンは1304年5月10日に逝去し、聖地を早期に奪還するという西欧の夢は潰えた[128]。

1307年に教皇クレメンス5世にモンゴル人についての彼のレポート を提示しているコリコスのヘイトン

14世紀、イルハン朝が1330年代に滅亡するまで、西欧とモンゴルの間の外交折衝は続いたが、ヨーロッパで黒死病と恐れられたペストの蔓延が起こり、東方との接触が途切れる原因となった[130]。ビザンチン帝国の皇帝アンドロニコス2世パレオロゴスがトクタ (1312年死去)との結婚で娘を与えたように、キリスト教国の支配者とジョチ・ウルスのモンゴル族との間で2、3の婚姻同盟は存続し、トクタの後継者であるウズベク・ハン (在位1312年-1341年) 以降も引き継がれた[131]。

アブー・サイードの後、キリスト教国の君主とイルハン朝の関係は、非常に希薄になった。アブー・サイードは後継者も相続人もないまま1335年に亡くなり、イルハン朝は彼の死をもって滅亡した。滅亡後は、モンゴル人、トルコ人、ペルシア人によって小国が群雄割拠する状態となった[14]。

1336年、アヴィニョン捕囚の教皇ベネディクトゥス12世への使節が、元の大都から、元の最後の皇帝トゴン・テムルによって送られた。使節はモンゴル皇帝の計らいにより2人のジェノヴァ人によって案内された。使節は、モンゴルが大都の大司教ジョヴァンニ・ダ・モンテコルヴィーノの死以来8年間、精神的な導きのないままであり、心から導きを求めていることを記した書簡を運んだ[132]。教皇ベネディクトゥス12世は、4人の聖職者を元の宮廷への使節に任命した。1338年、総勢50名もの聖職者が教皇から大都へ送られ、その中の1人のジョヴァンニ・デ・マリニョーリは1353年に元の皇帝から教皇インノケンティウス6世への書簡を携えてアヴィニョンに帰還した。しかしその後すぐ、漢民族が蜂起し、紅巾の乱が発生してモンゴル人を中国から追い払い、1368年に明王朝が成立した。1369年までに、すべての外国の影響は、モンゴル人からキリスト教徒、マニ教徒と仏教徒まで、明王朝によって追放された[133]。

1402年のティムールからフランス王シャルル6世への書簡

15世紀前半には、ティムールは、エジプトのマムルーク朝とオスマン帝国に対抗する同盟を構築しようとして、フランスのシャルル6世とカスティーリャ王国のエンリケ3世 (ただし1405年に死去) との関係強化に従事した (ティムール朝とヨーロッパの関係) [14][134][135][136][137]。

1300年頃のモンゴル帝国の領域。灰色の部分は、後のティムール朝。 モンゴルのイルハン朝に加え、元の大都にいる大ハーンと、ヨーロッパの地理的距離は大きかった。

なぜフランク・モンゴルの同盟が決して現実にならなかったか、そして、なぜそれがあらゆる外交折衝があったにもかかわらず、想像上の﹁キメラ﹂またはファンタジーのままであったのか、歴史家の間で多くの議論がなされてきた[2][8]。多くの理由が提案されてきた。一説には、彼らの帝国の活動範囲として、モンゴル人は西側に拡大することに全て集中するというわけではなかったということである。13世紀後半までには、モンゴルのリーダーは偉大なチンギス・カンから数世代離れており、内部分裂が始まっていた。チンギス・カンの統一の最初は遊牧民だったモンゴル人は、より定住するようになり、征服者から統治者に変わった。モンゴル民族に対するモンゴル民族の戦いが発生するようになり、モンゴル軍はシリア正面から去った[153]。聖地のイルハン朝のモンゴル人と、東欧でポーランドやハンガリーを攻撃していたジョチ・ウルスのモンゴル人の違いについて、欧州の中にも混同があった。モンゴル帝国の中で、イルハン朝とジョチ・ウルスは互いを敵と考えていたが、しかし、西側の第三者である西欧がモンゴル帝国の異なる地域を区別することが出来るまでには時間がかかった[153]。モンゴルの側でも、特に欧州で十字軍を継続することへの関心が減少していたため[152]、現時点で西欧がどの程度の兵力を集中させることが出来るかについて、懸念もあった[154]。モンゴルペルシャの宮廷歴史家は、イルハン朝とキリスト教西欧諸国との間のコミュニケーションには全く言及せずに、西欧諸国についてのみ言及していた。モンゴル人にとって連絡を取ることは明らかに重要には見えないため、困惑させた可能性があると考えられる。モンゴルの君主ガザン (1295年以降イスラム教に改宗) は、エジプトで彼と同じイスラム教徒に対して、異教徒の援助を得ようとするものとして知られていたくなかったのかもしれない。モンゴルの歴史家が外国の領域を書き留める時、領域は通常、﹁敵﹂か、﹁征服地﹂か、あるいは﹁反乱地域﹂として分類された。そのような状況で、征服すべき敵地として、欧州はエジプトと同じカテゴリーに挙げられていた。﹁同盟国﹂という認識は、モンゴル人とは無縁だった[155]。

一部のヨーロッパの君主は積極的にモンゴルの問合せに応じたが、実際に軍隊と物資の派遣を頼まれると、曖昧で回避的になった。エジプトのマムルーク軍はさらなる十字軍の派遣を強く心配したため、マムルーク軍が新たに城や港を攻略するたびに、それを占領せずに、二度と決して使われることができないように徹底的に破壊したため、欧州側の物流経路もより困難になった。このことは作戦を継続する上で十字軍にとって、より困難さを増し活動の出費を増やした。西欧の君主は、彼らの臣下に感情的に訴える方法として、十字軍に参加する考えにしばしばリップサービスを与えたが、しかし実際は、彼らは準備に何年もかけて、時には実際にレヴァント地域へ決して出発しなかった。欧州での地域紛争 (例えばシチリア晩祷戦争) も集中できない理由になり、欧州の貴族らは自らの軍隊を自領でより必要とするようになり、十字軍に預けたいと考えることもなくなってしまった[156][157]。

欧州側ではまた、モンゴルの長期目標も心配した。初期のモンゴルの外交は、単純な協力の申し入れでなく服従を求める直接の要求だった。モンゴルの使節がより懐柔的なトーン使い始めたのは、後期の通信だけだったが、それでも彼らは、嘆願よりもまだ多くの命令を意味した言葉を使用した。欧州とモンゴルの同盟について最も熱心な提唱者だったアルメニアの歴史家コリコスのヘイトンでさえも、モンゴルの指導者が欧州のアドバイスを聞きたいとは思っていないと率直に認めている。彼の忠告は、たとえ一緒に働くとしても、モンゴルの傲慢さを考慮すると、欧州の十字軍とモンゴル軍の接触は避けなければならないということだった。欧州の君主らは、モンゴルが聖地で立ち止まるだけで満足しておらず、世界支配のはっきりした野望があることを分かっていた。モンゴルが西欧諸国との同盟を成功裏に成し遂げて、マムルーク朝のスルタン国家を滅亡させたならば、結局、彼らはキプロスやビザンチン地域の欧州国家に確実に食ってかかっただろう[158]。彼らはまた、きっとエジプトを征服し、そこからムワッヒド朝やマリーン朝まで邪魔になる強国もないアフリカのマグレブ地方への前進を続けることが可能だった[153][159]。

そして最後に、モンゴルとの同盟について欧州の一般民衆の間で多くの支持はなかった。欧州の作家は、聖地を回復する最良の方法についての彼らの考えについて﹁回復﹂文献を作成していったが、実際の可能性としてモンゴル人に言及した人はごくわずかだった。1306年、教皇クレメンス5世が十字軍の継続についての提案を示すように、軍司令官のジャック・ド・モレーとフルク・ド・ヴィラレに尋ねた時、彼らはどちらもモンゴルとの同盟について少しも考慮に入れなかった。彼らは2、3の提案の後で、モンゴルについて、シリアを侵略することやマムルーク朝の群の気をそらしておくことは出来ても、共同作戦が期待できる力はないと簡単に説明しただけだった[153]。

オルジェイトゥ (1304–1316)[編集]

オルジェイトゥ、別名ムハンマド・フダーバンダは、イルハン朝開祖フレグの曾孫でガザンの弟であり、ガザンの跡を継いだ。青年時代に、彼は最初は仏教に、そして後に兄ガザンとともにイスラム教スンニ派に改宗して、名をイスラム風のムハンマドに変えた[129]。1305年4月、オルジェイトゥはフランスのフィリップ4世、教皇クレメンス5世およびイングランドのエドワード1世に書簡を送った。オルジェイトゥは、前任者ガザンと同様にマムルーク朝に対抗して、モンゴルと西欧のキリスト教国の間の軍事同盟を申し出た[57]。西欧諸国は新たな十字軍を計画しようとしたが進まなかった。一方、オルジェイトゥはマムルーク軍に対する最後の作戦を開始した(1312年–1313年)が、作戦は失敗に終わった。オルジェイトゥの息子アブー・サイードが1322年にアレッポの和約に署名し、マムルーク朝との最終的な和解が得られたのみだった[57]。最後の接触[編集]

文化的交流[編集]

文化的な面では、特にイタリアにおいて若干の西洋の中世芸術におけるモンゴルの要素が見られた。それについて、軍事同盟の機会が弱まった後、大部分が残っている作品は14世紀頃から存在する。これらはモンゴル帝国の織物と様々な文脈のモンゴル文字の描写を含んでおり、後者はしばしば時代錯誤だった。織物の輸入はイタリアの織物デザインに対してかなりの影響があった。モンゴル軍の軍装は兵士によって時折擦り切れて傷んでおり、概して殉教またはキリストの磔シーンのようなキリスト教の象徴に逆らったこれらの行動を思わせた。これらはおそらくモンゴルの欧州への使節によってもたらされた図画などから模倣されたか、あるいは、十字軍国家からもたらされた[138]。歴史家による史観[編集]

大部分の歴史家は、モンゴル帝国と西欧との接触について、一連の試み[139]、機会の損失[140][141][142]、失敗した交渉[1][113][139][143]と述べている。2004年にクリストファー・アトウッドは、﹁モンゴルとモンゴルの帝国の百科事典﹂の中で、西欧とモンゴルとの関係を要約しており、﹁多くの使節と共通の敵に対抗する同盟という明確な論理にもかかわらず、教皇政治と十字軍は、しばしば提案されたイスラム教徒に対抗する同盟をついに成し得なかった﹂と述べている[1]。 数人の他の歴史家は、実際の同盟があったと主張するが[122][144]、詳細については一致していない。ジーン・リチャードは、同盟が1263年頃に開始したと主張した[144]。ルーヴェン・アミタイは、実際にモンゴル軍と西欧軍の軍事連携に最も近いものはイングランドのエドワード皇太子が1271年にアバカと活動を調整しようとした時であると述べた。アミタイはまた、相互協力に向けた他の試みについても言及したが、﹁しかしこれらのエピソードのどれをとっても、同時にシリアの本土上にいた西欧諸国軍側からモンゴル軍の兵士に対して同盟について話すことが出来ていなかった﹂と述べている[91]。ティモシー・メイは、1274年の第2リヨン公会議が同盟に向かうピークだったが、1275年のボエモンの死去で崩れ始めたと述べており[145]、メイもそれぞれの軍隊が決して共同作戦にはつけなかったことを認めている[146]。アラン・ドゥマルジェは、彼自身の本﹁最後のテンプル騎士団﹂において、同盟は1300年まで捺印されていないと述べている[147]。 また、果たして同盟が賢い考えであったかどうか、そして、歴史上のこの時点で十字軍がペルシャとモンゴルの紛争にさえ関与できたかどうか、議論が続いている[8]。20世紀の歴史家グレン・バーガーは、﹁へトゥム1世の例に続いて、新たなモンゴル帝国と同盟することによって状況を変えることに適応することへのこの地域の東方キリスト教国家の拒絶は、十字軍国家の多くの失敗の中でも最も悲しいものの1つである﹂と述べた[148]。類似した見方を持つスティーブン・ランシマンは、﹁モンゴルとの同盟が成し遂げられて、西欧諸国によって誠実に同盟が実行されたならば、十字軍国家の存続はほぼ間違いなく長くなっていた。それらが滅亡していなければ、マムルーク朝は無力となり、ペルシアのイルハン朝は西欧キリスト教国家の強力な味方として存続していただろう﹂と主張した[149]。しかし、モンゴルを﹁潜在的同盟国﹂と記述した[150]デイビット・ニコールは、初期の歴史家が後知恵の恩恵からそう述べている[151]が、そもそも全体として、一流のプレーヤーはマムルーク朝とモンゴルだけで、キリスト教国はちょうど﹃より大きなゲームの駒﹄に過ぎなかった﹂と述べている[152]。同盟失敗の原因[編集]

脚注[編集]

- ^ a b c d e Atwood. "Western Europe and the Mongol Empire" in Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. p. 583. "Despite numerous envoys and the obvious logic of an alliance against mutual enemies, the papacy and the Crusaders never achieved the often-proposed alliance against Islam".

- ^ a b Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 4. "The failure of Ilkhanid-Western negotiations, and the reasons for it, are of particular importance in view of the widespread belief in the past that they might well have succeeded."

- ^ Many people in the East used the word "Frank" to denote a European of any variety.

- ^ a b c Ryan. pp. 411–421.

- ^ a b c d Morgan. "The Mongols and the Eastern Mediterranean". p. 204. "The authorities of the crusader states, with the exception of Antioch, opted for a neutrality favourable to the Mamluks."

- ^ a b c d Edbury. p. 105.

- ^ Demurger. "The Isle of Ruad". The Last Templar. pp. 95–110.

- ^ a b c See Abate and Marx. pp. 182–186, where the question debated is "Would a Latin-Ilkhan Mongol alliance have strengthened and preserved the Crusader States?'"

- ^ a b Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 46. See also pp. 181–182. "For the Mongols the mandate came to be valid for the whole world and not just for the nomadic tribes of the steppe. All nations were de jure subject to them, and anyone who opposed them was thereby a rebel (bulgha). In fact, the Turkish word employed for 'peace' was that used also to express subjection ... There could be no peace with the Mongols in the absence of submission."

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 121. "[The Mongols] had no allies, only subjects or enemies".

- ^ ドーソン『モンゴル帝国史』1巻、146頁

- ^ a b Foltz. pp. 111–112.

- ^ Amitai. "Mongol raids into Palestine (AD 1260 and 1300)". p. 236.

- ^ a b c d Knobler. pp. 181–197.

- ^ Quoted in Runciman. p. 246.

- ^ a b c d Morgan. The Mongols. pp. 133–138.

- ^ Richard. p. 422. "In all the conversations between the popes and the il-khans, this difference of approach remained: the il-khans spoke of military cooperation, the popes of adhering to the Christian faith."

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 72.

- ^ Tyerman. pp. 770–771.

- ^ Riley-Smith. pp. 289–290.

- ^ Tyerman. p. 772.

- ^ "In the Mongols' vocabulary, the terms for 'peace' and for 'subjection' were identical... The mere despatch of an embassy seemed tantamount to surrender." Jackson, p. 90

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 90.

- ^ Morgan. The Mongols. p. 102.

- ^ Dawson (ed.) The Mongol Mission. p. 86.

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 88.

- ^ 佐口透 編『モンゴル帝国と西洋』、p.63-65

- ^ Sinor. "Mongols in Western Europe". p. 522. "The Pope's reply to Baidju's letter, Viam agnoscere veritatis, dated November 22, 1248, and probably carried back by Aibeg and Sargis." Note that Sinor refers to the letter as "Viam agnoscere" though the actual letter uses the text "Viam cognoscere".

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 89.

- ^ Hindley. p. 193.

- ^ Bournotian. p. 109. "It was at this juncture that the main Mongol armies appeared [in Armenia] in 1236. The Mongols swiftly conquered the cities. Those who resisted were cruelly punished, while those submitting were rewarded. News of this spread quickly and resulted in the submission of all of historic Armenia and parts of Georgia by 1245 ... Armenian and Georgian military leaders had to serve in the Mongol army, where many of them perished in battle. In 1258 the Ilkhanid Mongols, under the leadership of Hulagu, sacked Baghdad, ended the Abbasid Caliphate and killed many Muslims."

- ^ Stewart. "Logic of Conquest". p. 8.

- ^ a b Nersessian. p. 653. "Hetoum tried to win the Latin princes over to the idea of a Christian-Mongol alliance, but could convince only Bohemond VI of Antioch."

- ^ Stewart. "Logic of Conquest". p. 8. "The Armenian king saw alliance with the Mongols — or, more accurately, swift and peaceful subjection to them — as the best course of action."

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 74. "King Het'um of Lesser Armenia, who had reflected profoundly upon the deliverance afforded by the Mongols from his neighbbours and enemies in Rum, sent his brother, the Constable Smbat (Sempad) to Guyug's court to offer his submission."

- ^ Ghazarian. p. 56.

- ^ May. p. 135.

- ^ Bournotian. p. 100. "Smbat met Kubali's brother, Mongke Khan and in 1247, made an alliance against the Muslims"

- ^ a b c d e Jackson. Mongols and the West. pp. 167–168.

- ^ Lebedel. p. 75. "The Barons of the Holy Land refused an alliance with the Mongols, except for the king of Armenia and Bohemond VI, prince of Antioch and Count of Tripoli"

- ^ a b c Tyerman. p. 806

- ^ Richard. p. 410. "Under the influence of his father-in-law, the king of Armenia, the prince of Antioch had opted for submission to Hulegu"

- ^ Richard. p. 411.

- ^ Saunders. p. 115.

- ^ Richard. p. 416. "In the meantime, [Baibars] conducted his troops to Antioch, and started to besiege the city, which was saved by a Mongol intervention"

- ^ a b Richard. pp. 414–420.

- ^ Hindley. p. 206.

- ^ Quoted in Grousset. p. 650.

- ^ a b c d Tyerman. pp. 815–818.

- ^ Jackson. "Crisis in the Holy Land". pp. 481–513.

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 181.

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 99.

- ^ Tyerman. p. 798. "Louis's embassy under Andrew of Longjumeau had returned in 1251 carrying a demand from the Mongol regent, Oghul Qaimush, for annual tribute, not at all what the king had anticipated."

- ^ Sinor. p. 524.

- ^ Tyerman. pp. 789–798.

- ^ Daftary. p. 60.

- ^ a b c d e Calmard. "France" article in Encyclopædia Iranica

- ^ Sinor. p. 531.

- ^ Demurger. Croisades et Croisés au Moyen Age. p. 285. "It really seems that Saint Louis's initial project in his second Crusade was an operation coordinated with the offensive of the Mongols."

- ^ a b Richard. pp. 428–434.

- ^ Grousset. p. 647.

- ^ Runciman. p. 303.

- ^ Lane. p. 243.

- ^ a b Angold. p. 387. "In May 1260, a Syrian painter gave a new twist to the iconography of the Exaltation of the Cross by showing Constantine and Helena with the features of Hulegu and his Christian wife Doquz Khatun".

- ^ Le Monde de la Bible N.184 July–August 2008. p. 43.

- ^ a b c Joseph p. 16.

- ^ a b Folda. pp. 349–350.

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 120.

- ^ Takahashi. p. 102.

- ^ Runciman. p. 304.

- ^ Irwin. p. 616.

- ^ Richard. pp. 414–415. "He [Qutuz] reinstated the emirs expelled by his predecessor, then assembled a large army, swollen by those who had fled from Syria during Hulegu's offensive, and set about recovering territory lost by the Muslims. Scattering in passage the thousand men left at Gaza by the Mongols, and having negotiated a passage along the coast with the Franks (who had received his emirs in Acre), he met and routed Kitbuqa's troops at Ayn Jalut."

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 116.

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 105.

- ^ Richard. p. 411.

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. pp. 120–122.

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 165.

- ^ Richard. pp. 409–414.

- ^ Tyerman. p. 807.

- ^ Richard. pp. 421–422. "What Hulegu was offering was an alliance. And, contrary to what has long been written by the best authorities, this offer was not in response to appeals from the Franks."

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 166.

- ^ Richard. p. 436. "In 1264, to the coalition between the Franks, Mongols and Byzantines, responded the coalition between the Golden Horde and the Mamluks."

- ^ Richard. p. 414. "In Frankish Syria, meanwhile, events had taken another direction. There was no longer any thought of conducting a crusade against the Mongols; the talk was now of a crusade in collaboration with them."

- ^ Reinert. p. 258.

- ^ Bisson. p. 70.

- ^ a b Hindley. pp. 205–207.

- ^ Nicolle. The Crusades. p. 47.

- ^ Richard. p. 433. "On landing at Acre, Edward at once sent his messengers to Abaga. He received a reply only in 1282, when he had left the Holy Land. The il-khan apologized for not having kept the agreed rendezvous, which seems to confirm that the crusaders of 1270 had devised their plan of campaign in the light of Mongol promises, and that these envisaged joint operation in 1271. In default of his own arrival and that of his army, Abaga ordered the commander of this forces stationed in Turkey, the 'noyan of the noyans', Samaghar, to descend into Syria to assist the crusaders."

- ^ Sicker. p. 123. "Abaqa now decided to send some 10,000 Mongol troops to join Edward's Crusader army".

- ^ Hindley. p. 207.

- ^ a b Amitai. "Edward of England and Abagha Ilkhan". p. 161.

- ^ a b Richard. p. 487. "1274: Promulgation of a Crusade, in liaison with the Mongols".

- ^ Setton. p. 116.

- ^ Richard. p. 422.

- ^ Biction de tout commerce avec les Sarasins, la fourniture de bateaux par les républiques maritimes italiennes, et une alliance de l'Occident avec Byzance et l'Il-Khan Abagha".

- ^ a b c d e f g Richard. pp. 452–456.

- ^ a b c Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 168.

- ^ a b c Amitai. Mongols and Mamluks. pp. 185–186.

- ^ a b Harpur. p. 116.

- ^ Jackson. "Mongols and Europe". p. 715.

- ^ Grands Documents de l'Histoire de France (2007), Archives Nationales de France. p. 38.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 169.

- ^ Glick. p. 485.

- ^ Fisher and Boyle. p. 370.

- ^ Rossabi. pp. 99, 173.

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. pp. 174–175.

- ^ Richard. p. 455.

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 170. "Arghun had persisted in the quest for a Western alliance right down to his death without ever taking the field against the mutual enemy."

- ^ Mantran. "A Turkish or Mongolian Islam" in The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages: 1250–1520. p. 298.

- ^ Phillips. p. 126.

- ^ a b Richard. p. 455.

- ^ a b Jackson. "Mongols and Europe". p. 715.

- ^ a b Tyerman. p. 816. "The Mongol alliance, despite six further embassies to the west between 1276 and 1291, led nowhere. The prospect of an anti-Mamluk coalition faded as the westerners' inaction rendered them useless as allies for the Mongols, who, in turn, would only seriously be considered by western rulers as potential partners in the event of a new crusade which never happened."

- ^ Richard. pp. 455–456. "When Ghazan got rid of him [Nawruz] (March 1297), he revived his projects against Egypt, and the rebellion of the Mamluk governor of Damascus, Saif al-Din Qipchaq, provided him with the opportunity for a new Syrian campaign; Franco-Mongol cooperation thus survived both the loss of Acre by the Franks and the conversion of the Mongols of Persia to Islam. It was to remain one of the givens of crusading politics until the peace treaty with the Mamluks, which was concluded only in 1322 by the khan Abu Said."

- ^ Amitai. "Ghazan's first campaign into Syria (1299–1300)". p. 222.

- ^ Barber. p. 22: "The aim was to link up with Ghazan, the Mongol Il-Khan of Persia, who had invited the Cypriots to participate in joint operations against the Mamluks".

- ^ a b Nicholson. p. 45.

- ^ Demurger. The Last Templar. p. 99.

- ^ Phillips. p. 128.

- ^ a b c Schein. p. 811.

- ^ a b Jotischky. p. 249.

- ^ a b c Demurger. The Last Templar. p. 100.

- ^ a b c d Barber. p. 22.

- ^ a b c Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 171.

- ^ Mutafian. pp. 74–75.

- ^ Richard. p. 469.

- ^ Nicolle. The Crusades. p. 80.

- ^ Demurger. The Last Templar. p. 109.

- ^ Stewart. Armenian Kingdom and the Mamluks. p. 181.

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 216.

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 203.

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 314.

- ^ Phillips. p. 112.

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 360.

- ^ Sinor. Inner Asia. p. 190.

- ^ Daniel and Mahdi. p. 25.

- ^ Wood. p. 136.

- ^ Mack. Throughout, but especially pp. 16–18, 36–40 (textiles), 151 (costume).

- ^ a b Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 173. "In their successive attempts to secure assistance from the Latin world, the Ilkhans took care to select personnel who would elicit the confidence of Western rulers and to impart a Christian complexion to their overtures."

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 119.

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 4.

- ^ Morgan. The Mongols. p. 136. "This has long been seen as a 'missed opportunity' for the Crusaders. According to that opinion, most eloquently expressed by Grousset and frequently repeated by other scholars, the Crusaders ought to have allied themselves with the pro-Christian, anti-Muslim Mongols against the Mamluks. They might thus have prevented their own destruction by the Mamluks in the succeeding decades, and possibly even have secured the return of Jerusalem by favour of the Mongols."

- ^ Prawer. p. 32. "The attempts of the crusaders to create an alliance with the Mongols failed."

- ^ a b Richard. pp. 424–469.

- ^ May. p. 152.

- ^ May. p. 154.

- ^ Demurger. The Last Templar. p. 100. "Above all, the expedition made manifest the unity of the Cypriot Franks and, through a material act, put the seal on the Mongol alliance."

- ^ Burger. pp. xiii–xiv. "The refusal of the Latin Christian states in the area to follow Hethum's example and adapt to changing conditions by allying themselves with the new Mongol empire must stand as one of the saddest of the many failures of Outremer."

- ^ Runciman. p. 402.

- ^ Nicolle. The Crusades. p. 42. "The Mongol Hordes under Genghis Khan and his descendants had already invaded the eastern Islamic world, raising visions in Europe of a potent new ally, which would join Christians in destroying Islam. Even after the Mongol invasion of Orthodox Christian Russia, followed by their terrifying rampage across Catholic Hungary and parts of Poland, many in the West still regarded the Mongols as potential allies."

- ^ Nicolle and Hook. The Mongol Warlords. p. 114. "In later years Christian chroniclers would bemoan a lost opportunity in which Crusaders and Mongols might have joined forces to defeat the Muslims. But they were writing from the benefit of hindsight, after the Crusader States had been destroyed by the Muslim Mamluks."

- ^ a b Nicolle. The Crusades. p. 44. "Eventually the conversion of the Il-Khans (as the Mongol occupiers of Persia and Iraq were known) to Islam at the end of the 13th century meant that the struggle became one between rival Muslim dynasties rather than between Muslims and alien outsiders. Though the feeble Crusader States and occasional Crusading expeditions from the West were drawn in, the Crusaders were now little more than pawns in a greater game."

- ^ a b c d Jackson. Mongols and the West. pp. 165–185.

- ^ Amitai. "Edward of England and Abagha Ilkhan". p. 81.

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. pp. 121, 180–181.

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 179.

- ^ Phillips. p. 130.

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 183.

- ^ Amitai. "Mongol imperial ideology". p. 59.

参考文献[編集]

- Abate, Mark T.; Marx, Todd (2002). History in Dispute: The Crusades, 1095–1291. 10. Detroit, Michigan, USA: St. James Press. ISBN 978-1-55862-454-2

- Amitai, Reuven (1987). “Mongol Raids into Palestine (AD 1260 and 1300)”. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (Cambridge, UK; New York, New York, USA: Cambridge University Press) (2): 236–255. JSTOR 25212151.

- Amitai-Preiss, Reuven (1995). Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War, 1260–1281. Cambridge, UK; New York, New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-46226-6

- Amitai-Preiss, Reuven (1999). “Mongol imperial ideology and the Ilkhanid war against the Mamluks”. In Morgan, David; Amitai-Preiss, Reuven. The Mongol empire and its legacy. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11048-9

- Amitai, Reuven (2001). “Edward of England and Abagha Ilkhan: A reexamination of a failed attempt at Mongol-Frankish cooperation”. In Gervers, Michael; Powell, James M. (editors). Tolerance and Intolerance: Social Conflict in the Age of the Crusades. Syracuse, New York, USA: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-2869-9

- Amitai, Reuven (2007). “Whither the Ilkhanid army: Ghazan's first campaign into Syria (1299–1300)”. The Mongols in the Islamic lands: studies in the history of the Ilkhanate. Burlington, Vermont, USA: Ashgate/Variorium. ISBN 978-0-7546-5914-3

- Angold, Michael, ed (2006). Cambridge History of Christianity: Eastern Christianity. 5. Cambridge, UK; New York, New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521811132. ISBN 978-0-521-81113-2

- Atwood, Christopher P. (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. New York, New York, USA: Facts on File, Inc.. ISBN 978-0-8160-4671-3

- Balard, Michel (2006). Les Latins en Orient (XIe–XVe siècle). Paris, France: Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 978-2-13-051811-2

- Barber, Malcolm (2001). The Trial of the Templars (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK; New York, New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-67236-8

- Bisson, Thomas N. (1986). The Medieval Crown of Aragon: A Short History. New York, New York, USA: Clarendon Press [Oxford University Press]. ISBN 978-0-19-821987-3

- Bournoutian, George A. (2002). A Concise History of the Armenian People: From Ancient Times to the Present. Costa Mesa, California, USA: Mazda Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56859-141-4

- Burger, Glenn (1988). A Lytell Cronycle: Richard Pynson's Translation (c. 1520) of La Fleur des histoires de la terre d'Orient (Hetoum c. 1307). Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-2626-2

- Calmard, Jean. “Encyclopædia Iranica”. Costa Mesa, California, USA: Mazda Publishers. 2010年3月27日閲覧。

- Daftary, Farhad (1994). The Assassin Legends: Myths of the Isma'ilis. London, UK; New York, New York, USA: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-705-5

- Daniel, Elton L.; Ali Akbar Mahdi (2006). Culture and Customs of Iran. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-32053-8

- Dawson, Christopher (1955). The Mongol Mission: Narratives and Letters of the Franciscan Missionaries in Mongolia and China in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Translated by a nun of Stanbrook Abbey. New York, New York, USA: Sheed and Ward. ISBN 978-1-4051-3539-9

- Demurger, Alain (2005) [First published in French in 2002, translated to English in 2004 by Antonia Nevill]. The Last Templar. London, UK: Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-86197-553-9

- Demurger, Alain (2006) (French). Croisades et Croisés au Moyen Age. Paris, France: Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-08-080137-1

- Edbury, Peter W. (1991). Kingdom of Cyprus and the Crusades, 1191–1374. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-26876-9

- Fisher, William Bayne; Boyle, John Andrew (1968). The Cambridge history of Iran. 5. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-06936-X

- Folda, Jaroslav (2005). Crusader art in the Holy Land: from the Third Crusade to the fall of Acre. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83583-1

- Foltz, Richard C. (1999). Religions of the Silk Road: Overland Trade and Cultural Exchange from Antiquity to the Fifteenth Century. New York, New York, USA: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-23338-9

- Ghazarian, Jacob G. (2000). The Armenian kingdom in Cilicia during the Crusades. Surrey, England, UK: Curzon Press. ISBN 978-0-7007-1418-6

- Glick, Thomas F.; Livesey, Steven John; Wallis, Faith (2005). Medieval science, technology, and medicine: an encyclopedia. New York, New York, USA: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-96930-7

- Grousset, René (1936) (French). Histoire des Croisades III, 1188–1291 L'anarchie franque. Paris, France: Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-02569-4

- Harpur, James (2008). The Crusades: The Two Hundred Years War: The Clash Between the Cross and the Crescent in the Middle East. New York, New York, USA: Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-4042-1367-8

- Hindley, Geoffrey (2004). The Crusades: Islam and Christianity in the Struggle for World Supremacy. New York, New York, USA: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7867-1344-8

- Irwin, Robert (1999). “The Rise of the Mamluks”. In Abulafia, David; McKitterick, Rosamond (editors). The New Cambridge Medieval History V: c. 1198–c. 1300. Cambridge, UK; New York, New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. p. 616. ISBN 978-0-521-36289-4

- Jackson, Peter (July 1980). “The Crisis in the Holy Land in 1260”. The English Historical Review (London, UK; New York, New York, USA: Oxford University Press) 95 (376): 481–513. doi:10.1093/ehr/XCV.CCCLXXVI.481. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 568054.

- Jackson, Peter (2000). “The Mongols and Europe”. In Abulafia, David; McKitterick, Rosamond (editors). The New Cambridge Medieval History V: c. 1198–c. 1300. Cambridge, UK; New York, New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. p. 703. ISBN 978-0-521-36292-4

- Jackson, Peter (2005). The Mongols and the West: 1221–1410. Harlow, UK; New York, New York, USA: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-36896-5

- Joseph, John (1983). Muslim-Christian Relations and Inter-Christian Rivalries in the Middle East: The Case of the Jacobites in an Age of Transition. Albany, New York, USA: SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-87395-600-0

- Jotischky, Andrew (2004). Crusading and the Crusader States. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-582-41851-6

- Knobler, Adam (Fall 1996). “Pseudo-Conversions and Patchwork Pedigrees: The Christianization of Muslim Princes and the Diplomacy of Holy War”. Journal of World History (Honolulu, Hawaii, USA: University of Hawaii Press) 7 (2): 181–197. doi:10.1353/jwh.2005.0040. ISSN 1045-6007.

- Knobler, Adam. 1996. "Pseudo-conversions and Patchwork Pedigrees: The Christianization of Muslim Princes and the Diplomacy of Holy War". Journal of World History 7 (2). University of Hawai'i Press: 181–97. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20078675.

- Lane, George (2006). Daily Life in the Mongol Empire. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33226-5

- Lebédel, Claude (2006) (French). Les Croisades, Origines et Conséquences. Rennes, France: Editions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-2-7373-4136-6

- Mack, Rosamond E. (2002). Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300–1600. Berkeley, California, USA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22131-4

- Mantran, Robert (1986). “A Turkish or Mongolian Islam”. In Fossier, Robert. The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages: 1250–1520. 3. trans. Hanbury-Tenison, Sarah. Cambridge, UK; New York, New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. p. 298. ISBN 978-0-521-26646-8

- Marshall, Christopher (1994). Warfare in the Latin East, 1192–1291. Cambridge, UK; New York, New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47742-0

- May, Timothy M. (2002). “The Mongol Presence and Impact in the Lands of the Eastern Mediterranean”. In Kagay, Donald J.; Villalon, L. J. Andrew. Crusaders, condottieri, and cannon. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12553-7

- Michaud, Yahia (Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies) (2002) (French). Ibn Taymiyya, Textes Spirituels I–XVI. Le Musulman, Oxford-Le Chebec

- Morgan, David (June 1989). Arbel, B.; et al.. ed. “The Mongols and the Eastern Mediterranean: Latins and Greeks in the Eastern Mediterranean after 1204”. Mediterranean Historical Review (Tel Aviv, Israel; Chicago, Illinois, USA: Routledge) 4 (1): 204. doi:10.1080/09518968908569567. ISSN 0951-8967.

- Morgan, David (2007). The Mongols (2nd ed.). Malden, Massachusetts, USA; Oxford, UK; Carlton, Victoria, AU: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-3539-9

- Mutafian, Claude (2002) [1993] (French). Le Royaume Arménien de Cilicie, XIIe-XIVe siècle. Paris, France: CNRS Editions. ISBN 978-2-271-05105-9

- Nersessian, Sirarpie Der (1969). “The Kingdom of Cilician Armenia”. In Hazard, Harry W., Wolff, Robert Lee. (Kenneth M. Setton, general). A History of the Crusades: The Later Crusades, 1189–1311. 2. Madison, Wisconsin, USA: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 630–660. ISBN 978-0-299-04844-0

- Nicholson, Helen (2001). The Knights Hospitaller. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK; Rochester, New York, USA: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-845-7

- Nicolle, David (2001). The Crusades. Essential Histories. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-179-4

- Nicolle, David; Hook, Richard (2004). The Mongol Warlords: Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulegu, Tamerlane. London, UK: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 978-1-86019-407-8

- Phillips, John Roland Seymour (1998). The Medieval Expansion of Europe (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820740-5

- Prawer, Joshua (1972). The Crusaders' Kingdom: European Colonialism in the Middle Ages. New York, New York, USA: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-297-99397-1

- Reinert, Stephen W. (2002). “Fragmentation (1204–1453)”. In Mango, Cyril A.. The Oxford History of Byzantium. Oxford, UK; New York, New York, USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814098-6

- Richard, Jean (1969). “The Mongols and the Franks”. Journal of Asian History 3 (1): 45–57.

- Richard, Jean (1999) [published in French 1996]. The Crusades, c. 1071–c. 1291. trans. Birrell, Jean. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62566-1

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2005). Crusades: A History (2nd ed.). London, UK; New York, New York, USA: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-7270-0

- Rossabi, Morris (1992). Voyager from Xanadu: Rabban Sauma and the First Journey from China to the West. Tokyo, Japan; New York, New York, USA: Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4-7700-1650-8

- Runciman, Steven (1987) [first published in 1951]. A History of the Crusades, Vol. III: The Kingdom of Acre and the Later Crusades (3rd ed.). Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-013705-7

- Ryan, James D. (November 1998). “Christian Wives of Mongol Khans: Tartar Queens and Missionary Expectations in Asia”. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (Cambridge, UK; New York, New York, USA: Cambridge University Press) 8 (3): 411–421. doi:10.1017/S1356186300010506. JSTOR 25183572.

- Saunders, John Joseph (2001) [1971]. The History of the Mongol Conquests. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1766-7

- Schein, Sylvia (October 1979). “Gesta Dei per Mongolos 1300. The Genesis of a Non-Event”. The English Historical Review (London, UK; New York, New York, USA: Oxford University Press) 94 (373): 805–819. doi:10.1093/ehr/XCIV.CCCLXXIII.805. JSTOR 565554.

- Setton, Kenneth (1984). The Papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571. The sixteenth century to the reign of Julius III, Volume 3. Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society; volume 114. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-114-9

- Sicker, Martin (2000). The Islamic World in Ascendancy: From the Arab Conquests to the Siege of Vienna. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-96892-2

- Sinor, Denis (1975). “The Mongols and Western Europe”. In Setton, Kenneth Meyer (gen ed); Hazard, Harry W.. A History of the Crusades: The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries. 3. Madison, Wisconsin, USA: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 513. ISBN 978-0-299-06670-3

- Sinor, Denis (1997). Inner Asia: Uralic and Altaic series, Volumes 1–150, 1960–1990. 96. London, UK: Routledge/Curzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-0896-3

- Stewart, Angus Donal (2001). The Armenian Kingdom and the Mamluks: War and Diplomacy During the Reigns of Het'um II (1289–1307). 34. Leiden, Netherlands; Boston, Massachusetts, USA: BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-12292-5

- Stewart, Angus (January 2002). “The Logic of Conquest: Tripoli, 1289; Acre, 1291; why not Sis, 1293?”. Al-Masaq: Islam and the Medieval Mediterranean (London, UK: Routledge) 14 (1): 7–16. doi:10.1080/09503110220114407. ISSN 0950-3110.

- Takahashi, Hidemi (2005). Barhebraeus: a Bio-Bibliography. Piscataway, New Jersey, USA: Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-148-1

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God's War: A New History of the Crusades. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02387-1

- Wood, Frances (2002). The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia. Berkeley, California, USA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24340-8